We started exploring plan reading last October with a look at stationing and then in January we explained various “views” one encounters in construction plans. If you thought those were exciting, you are going to love it as we turn our attention to shop drawings and their almost twin-brother, working drawings.

Let’s think about the progression of plans from their earliest conception. Somewhere at the beginning, a designer is sketching something out on a napkin or the back of an envelope and that evolves into the design work, calculations, and so forth. When the design is complete, a set of construction plans (and all the specifications and other supporting documents) come together to build the base of what will be the contract documents. But for many elements, the construction plans are not as complete as they first appear. For any number of things, which we will explore here, the construction plans and specifications leave it up to the contractor and subcontractors to detail how they intend to fulfill the contract requirements, the sources and materials they will use, temporary works, structural minutiae, and so on. This is where submittals, shop drawings and working drawings come in.

The contractor will normally provide many submittals, depending upon the nature of the work, including such things as project schedules, sources of materials (aggregate, cement, etc.), design mixes (think concrete or asphalt), hot/cold weather placement plans (think concrete), quality control plans, placement plans (e.g., deck pours, heavy beam placement, etc.), repair details, catalog cuts for miscellaneous materials, etc. Shop drawings and work drawings are usually thought of as categories of submittals.

Depending upon the agency procuring the work, shop drawings and working drawings are often used interchangeably. In the Delaware Department of Transportation’s (DelDOT) “Standard Specifications for Road and Bridge Construction,” shop drawings are defined as “contractor drawings that provide details for fabricating or constructing an element of work to be permanently incorporated into the project,” and working drawings are defined as “drawings and data not in the contract that the contractor is required to submit to the engineer showing how the contractor will perform specific work such as building cofferdams or falsework.” While they are defined separately, only working drawings are included in the “complete body of documents” defining “contract,” and they are largely lumped together with shop drawings throughout the Standard Specifications.

For our purposes, we won’t dwell further on the distinction in terms and you should instead pay close attention to how the specifications for your project defines them. Instead, let’s discuss the nature of some example shop drawings and how they relate to the construction or bid plans.

In general, shop drawings and working drawings show in detail the proposed fabrication and assembly of structural elements, and the installation (i.e., fit, and attachment details) of materials or equipment. They can include drawings, diagrams, layouts, schematics, descriptive literature, illustrations, schedules, performance and test data, and similar materials furnished by the contractor to explain in detail specific portions of the work required by the contract.

In terms of what some think of as working drawings, many projects have temporary support work, false work, and the like. For example, there may be platforms to support bridge painting, containment systems, temporary steel plates, trench boxes, or a cofferdam to allow construction of footings in dry conditions. While these may not be components of the final construction, they must be engineered to ensure they provide safety to the workers and traveling public while also allowing adequate room and support for the work to be completed properly. Normally, calculations and plans for these temporary works must be sealed by the Professional Engineer completing the design. The contractor makes a submittal for acceptance by the owner agency (rarely does the owner’s engineer “approve” the submittal – the design responsibility remains with the contractor).

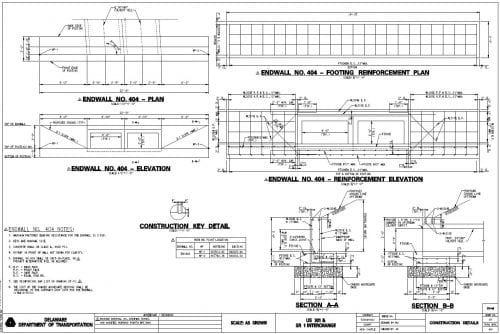

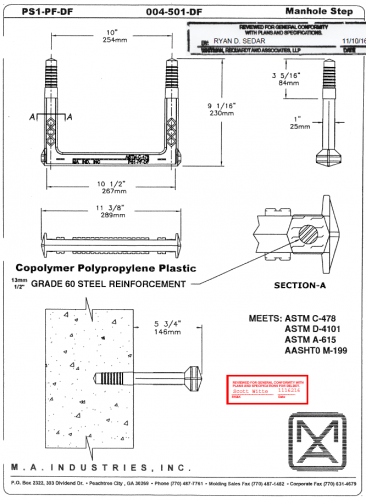

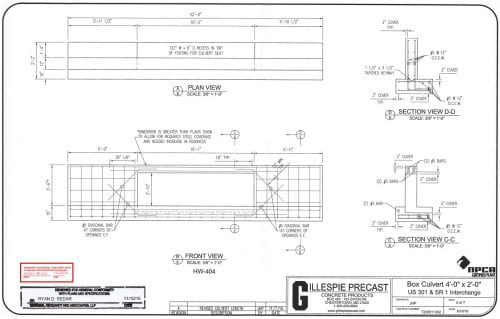

A classic example of a shop drawing would be for a drainage structure, such as a storm drain inlet or a manhole. In the contract or bid documents, the structure will be sized and other details will be provided to guide the contractor’s detailer as to the design requirements. The detailer in this example might be the precast company that will provide the structures. The detailer provides a much more complete set of drawings that show thicknesses of walls, floors, and covers, reinforcing bar (rebar) details, joints, step placements, openings, reinforcing around openings, grates, lifting lugs, and so on. In addition, there are usually catalog cuts for seals, sealants, grouts, mechanical pieces (like lifting lugs, steps, and grates), etc. By reviewing the shop drawing, the design engineer can be satisfied that what the precaster intends to build will be consistent with the design intent and needs. Again, more often than not, these also will require a Professional Engineer’s seal from the detailer.

For precast or cast-in-place concrete structures of any kind, shop drawings are particularly important for rebar details. These will show types and size of rebar (usually in lists), bending diagrams, location of each type of bar, lengths, tying schedules, splices, bar coatings, bar supports, shipping and storage requirements, and other details.

Steel structures such as beams, bearings, shear connectors, or platforms require shop drawings as well. These will include the type of steel to be used in each element, fastening (bolts, welds, gusset plates, rivets, etc.), dimensional details of the members, camber details, horizontal curve diagrams, general shop notes, splicing diagrams, stiffeners, and lots of lists. Here, the AASHTO/NSBA Steel Bridges Collaboration G1.3 Shop Detail Drawing Presentation Guidelines will often be the reference standard. In DelDOT’s Standard Specifications, a Professional Engineer’s stamp is not required for steel structure shop drawings.

Guardrail and end treatment systems are yet another typical example where shop drawings are required. For guardrail systems to perform as designed, no detail is too small – a missing washer or a substituted bolt can be an unacceptable difference. As such, guardrail shop drawings will include items such as the type of steel, coatings, and shape of the rail, but also the precise bolt patterns, the bolts, washers, and nuts themselves, post designs and connections, as well as connections to structural members (such as bridge parapets) or end treatments. Impact attenuators (known also by some 15 other names) are terribly critical to safety performance, so the attenuators themselves along with the connection details to the rest of the guardrail system will be heavily detailed, as well as details for installation, such as bolt torque.

Street lighting (luminaires) are another example of installation that would normally require shop drawings. These might take the form of catalog cuts for simpler designs, but they still must detail things like the lamp types, materials, dimensions, crashworthy (if within the Clear Zone) connections, wiring connections, and so on. Of course, they must also demonstrate compliance with the design intent for light distribution and intensity (often by way of a mathematical model and plan), glare mitigation, light colors, etc.

These examples should give you an idea of the kind of shop drawings and working drawings that should play a part in your project and the role they play in the constructed project. In essence, these submittals (aside from the mixing and matching of names) fall into two basic categories. The first deal with temporary or support works, while the second can be thought of as detailing form, fit, and attachment details consistent with the design shown in the contract or bid drawings.

In most cases these days, the contractor submits shop drawings and working drawings and the owner’s engineer reviews the design documents for contract “conformance.” The engineer then either returns them for revision or accepts them (sometimes with comments or requirements). Rarely does the owner’s engineer “approve” the submittal these days, as the final responsibility for these details rests with the contractor.

Contractor submittals, including but not limited to shop drawings and working drawings, are an essential part of contract management to ensure that, before elements are manufactured or installed, the work will conform with the design intent and deliver the performance that is sought.

The Delaware T2/LTAP Center’s Municipal Engineering Circuit Rider is intended to provide technical assistance and training to local agencies and so if you have construction management questions or other transportation issues, contact Matt Carter at matheu@udel.edu or (302) 831-7236.

You must be logged in to post a comment.