Chris Hernandez and Christian Poindexter

Soreness is a typical and often expected side effect of any moderate level of physical activity or exercise. However, contrary to popular belief, there are many different types of soreness which are a result of separate things. For example, the soreness that many people experience during or immediately after exercise is known as acute soreness. Acute soreness typically develops within a couple of minutes of the muscle contraction and dissipates within anywhere from a few minutes to several hours after the contractions have ended[1]. It is widely accepted that this soreness is a result of the accumulation of chemical byproducts, tissue edema, or muscle fatigue. Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS) typically develops between 12-24 hours after muscle contractions end, with peak ‘soreness’ being experienced 24-72 hours after the exercise is over[1]. Exercises typically associated with DOMS include strength training exercise, jogging, walking down hills, jumping, and step aerobics. Apart from soreness, people suffering from DOMS also experience swelling in their sore limbs, stiffness of adjacent joints, tenderness to the touch, and temporary reduction of strength in affected muscle[1]. Unlike with acute soreness, there are several competing theories on the cause of DOMS, none of which have been ultimately proven to be the predominant cause.

One of the first and most touted theories was the Lactic Acid Theory. This was based on the concept that the muscles continue to produce and accumulate lactic acid even after the exercise is abated. The accumulation of this lactic acid is thought to cause the noxious stimulus associated with soreness[2]. The paper we are using, “Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness: Treatment Strategies and Performance Factors”, cited a study done by French researchers regarding misconceptions about lactic acid, and more specifically lactate[3]. This study goes on to explain that during the recovery phase post-contraction, accumulated lactate gets oxidized by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) into pyruvate. This pyruvate is either oxidized in the mitochondria where it contributes to the resynthesis of ATP, or it is transported in the blood to be used or disposed of elsewhere in the body[3]. It has been observed that for test subjects whose lactate levels were monitored for 72 hours before, during, and after exercise, their lactic acid levels returned to pre-exercise levels within 1 hour of the cessation of exercise[2]. Since DOMS does not set in for 24-48 hours, it is very unlikely that lactic acid accumulation is the cause of the pain and other symptoms associated with this disease.

These researchers did note some conditions however that were noted to affect the lactate levels of those participating in the study. For example, a participant with a diet rich or low in carbohydrate concentrations can cause lactate levels to decrease or increase respectively[3]. Further, participants who had undergone strenuous exercise the day before are likely to show signs of glycogenic depletion, which could cause them to have irregular lactate levels[3]. Further, the type of exercise performed was also shown to have an effect on not only lactate levels but also on the time frame required for levels to return to normal[3]. To improve this study and potentially get better results it would be best to make sure that all test subjects were undergoing the same exercise regimens. It would also be beneficial if the amount of carbohydrates (based on body weight) was held standard, and that they all experienced 48 hours of rest before data collection[3]. However, even given these potential weaknesses, given that the lactate levels return to below normal within an hour of exercise cessation, it can be said with reasonable certainty that lactic acid is not the cause of DOMS[2,3].

A more current and well-supported theory is the Muscle Damage theory, which is based on the disruption of the contractile component of muscle tissue after eccentric exercise. Type II fibers have the narrowest z-lines and are particularly susceptible to this type of disruption. Nociceptors located in the muscle connective tissue and in the surrounding tissues are stimulated, which leads to the sensation of pain that we know as DOMS. In practice, muscle soluble enzymes can be used as an indicator of z-line disruption and sarcolemma damage. Creatine Kinase (CK) is used as one of these muscle permeability indicators; any disruption of the z-lines and damage to the sarcolemma will enable the diffusion of CK into the interstitial fluid, where it can be measured.

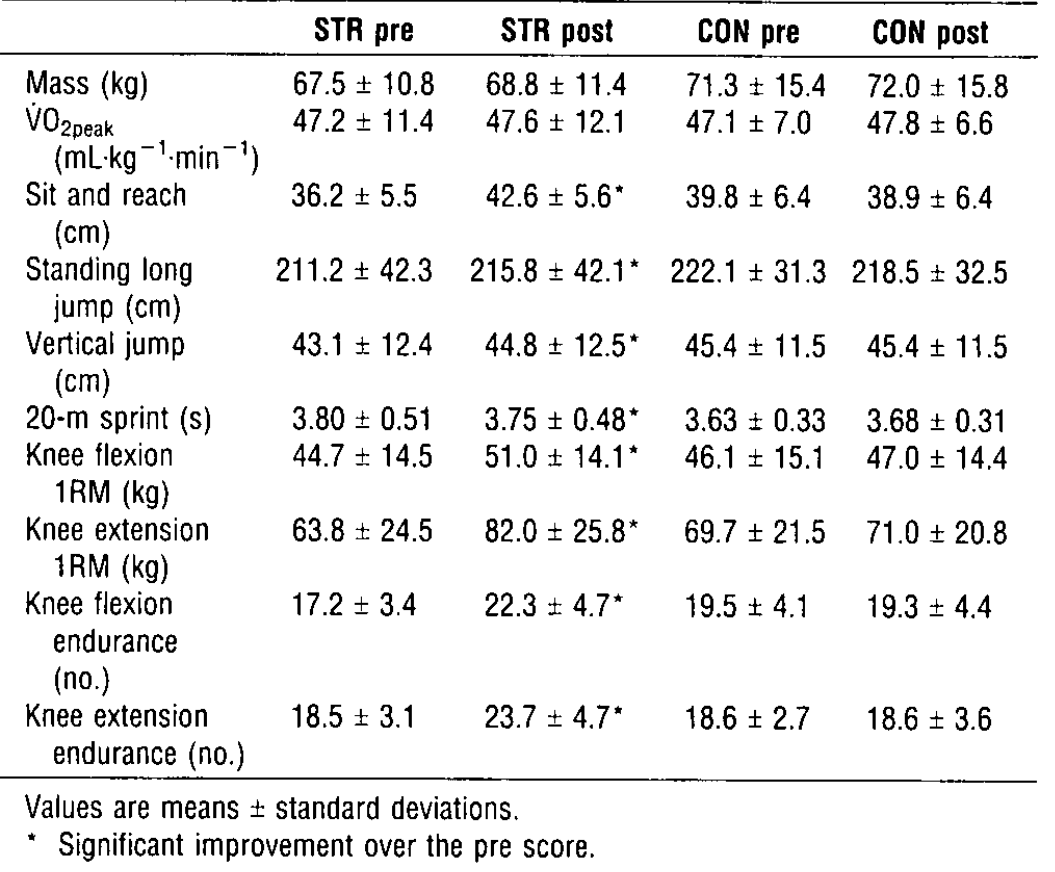

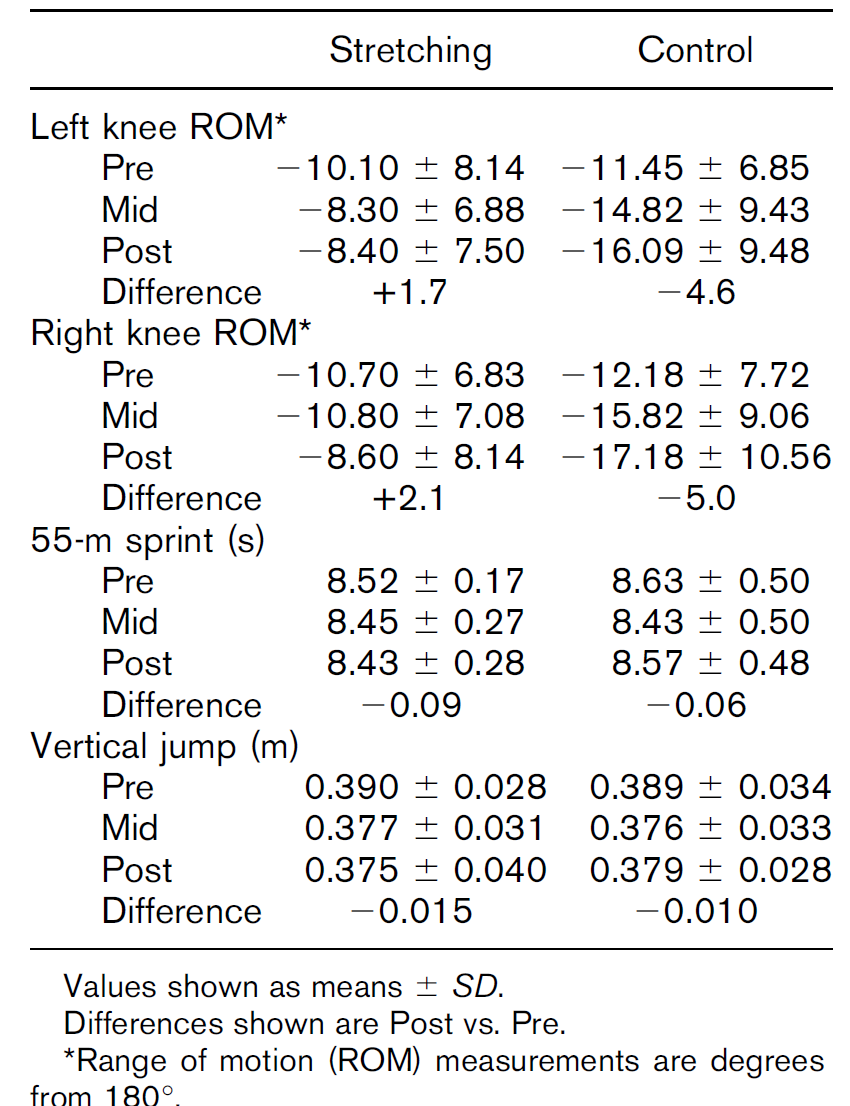

To test the connection between eccentric exercise and changes in CK, this study[4] used five healthy adults and had them walk on a treadmill for an hour at a 13-degree incline to test the effect of concentric exercise, and then a 13-degree decline five weeks later to test eccentric exercise. Venous blood samples were taken pre-test and every 24 hours until CK levels had returned to pre-exercise levels. Following downhill walking, all subjects reported muscle pain and tenderness in the calves and glutei muscles, which developed several hours post-exercise and was maximal between 1-2 days after. The severity of pain differed between subjects, but following uphill walking none reported any pain or tenderness. Both concentric and eccentric exercises showed increases in CK levels, but eccentric work showed much greater levels and peaked after 4-7 post exercise, as shown in figures 1-2.

Newham, et al. conclude that rises in CK levels are a result of eccentric work, and suggests that the extent to which muscle is lengthened and the level of habituation to eccentric work play a role in the enzyme response, and thereby in DOMS. However, they acknowledge that there is only a correlation between CK levels and DOMS and not necessarily a causation. Additionally, the sample size they used is small which could lead to inaccurate data.

There are many theories of the cause of DOMS, and none can fully explain the phenomenon. A combination of models has also been proposed[5], drawing aspects from various theories. Of the two theories we examined, the muscle damage theory was the most conclusive, showing a relationship between plasma CK levels and DOMS. Additional studies will be necessary to determine whether the muscle damage theory, another theory or possibly a combination of multiple can best explain the symptoms of DOMS.

Questions to Consider:

- Which types of exercise would help to prevent DOMS?

- How would you better design an experiment to correlate DOMS with enzyme activity?

- Can we conclusively rule out lactic acid as an explanation?

References/Further Reading:

[1] American College of Sports Medicine. Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness. Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness, American College of Sports Medicine, 2011, www.acsm.org/docs/brochures/delayed-onset-muscle-soreness-(doms).pdf.

[2] Schwane JA, Hatrous BG, Johnson SR, et al. Is lactic acid 63. Hasson SM, Wible CL, Reich M, et al. Dexamethasone related to delayed-onset muscle soreness? Phys Sports Med phoresis: effect on delayed muscle soreness and muscle function 1983; 11 (3): 124-7, 130-1

[3]Léger , L., Cazorla , G., Petibois , C. & Bosquet , L. (2001). Lactate and exercise: myths and realities. Staps , n o 54, (1), 63-76. doi: 10.3917 / sta.054.0063.

[4]Newham, D. J., Jones, D. A., & Edwards, R. H. T. (January 01, 1986). Plasma creatine kinase changes after eccentric and concentric contractions. Muscle & Nerve, 9, 1, 59-63.

[5]Cheung, K., Hume, P. A., & Maxwell, L. (2003). Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness. Sports Medicine,33(2), 145-164. doi:10.2165/00007256-200333020-00005

[6]Armstrong, R. B. (January 01, 1990). Initial events in exercise-induced muscular injury. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 22, 4, 429-35.