By Claire Paddock, Nick Ruggiero, and Dan Smith

Everyone knows the story. The Florida Gators football coach needed a way to keep his athletes hydrated and replace the electrolytes that they lost during practice and games in the heat. Scientists at the University of Florida College of Medicine created a beverage that contained exactly what the players needed. The rest is history. Gatorade is the go-to for good tasting hydration.

Gatorade contains water, sugar, and salt (among other ingredients), to both hydrate and replace the carbohydrates and electrolytes lost in sweat while exercising. Top athletes deplete these materials in their body while exercising, and if they lose too much, it could prove to be dangerous. For example, there have been numerous cases of marathon runners becoming ill and suffering from pulmonary edema and seizures, even after drinking water throughout the marathon. Why? Hyponatremia, a condition caused by lack of sodium in the blood. These athletes were replacing the water they sweated out, but none of the electrolytes. If they had been drinking a beverage like Gatorade that had the necessary salt in it, perhaps they wouldn’t have suffered from such an extreme condition.

Staying hydrated is important not just for top athletes, but for the rest of us too. Data shows that staying hydrated is key to both physical and cognitive performance. However, after exercise, do those of us who don’t train like professional athletes really need to be reaching for a sports drink like Gatorade?

Gatorade, and other sports drinks, have been shown to hydrate trained athletes more efficiently than regular water. A study showed that in distance kayakers after one hour of paddling, there was a significant difference between those who were given water and those who were given Gatorade. The water group showed a mean percentage dehydration of 1.1% compared to gatorades .72%. This study also looked at volume of fluid consumed, urine output, urine specific gravity, mean loss in body mass, mean estimated water loss, and mean time of maximal exertion. While there was no statistical difference between the groups in urine output, specific gravity, volume consumed, or estimated water loss; there was a difference in percentage dehydration, loss in body mass, and time of maximal exertion with the Gatorade group showing higher results. These results show that athletes who drank Gatorade over a 1 hour paddle were more hydrated than those who drank water and that these athletes were able to maintain their maximal level of exertion longer, possibly as a result of being better hydrated. While this study only looked at a 1 hour paddle and not a typical 3 hour marathon race, the group hypothesizes that these differences in hydration would be even more apparent over longer distances.

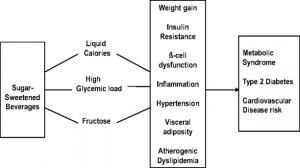

Sugar-Sweetend Beverages (SSBs) like Gatorade, when consumed in excess, can lead to health conditions such as Type 2 diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease

While we know that Gatorade is important for hydration over long periods of exercise, it is actually not necessary for the average person. Obesity is an ever increasing problem around the world and Sugar-Sweetened Beverages (SSBs) are at the heart of the issue. There is evidence that SSBs like Gatorade, which contains 34g of sugar per 20 fl oz. serving, are contributing to the obesity epidemic, especially during childhood. Childhood obesity can often lead to adult obesity, bringing health conditions such as Type II Diabetes and Cardiovascular diseases with it. Individuals who consumed more than one soft drink per day had a 22% increase in incidences of hypertension, high blood pressure, than those who did not consume SSBs.

Our investigation into whether or not Gatorade should be consumed by the average individual did not bring about surprising results. First, we investigated the efficacy of Gatorade to see if it was as beneficial as it is marketed to be. While we determined that it is indeed a better way to rehydrate than water we were unable to find studies focused on untrained individuals who performed significantly less training volume than their trained counterparts. While SSBs like Gatorade should be avoided in a child’s diet as they may contribute to obesity, we did find that during exercise, particularly in hot and humid environments, Gatorade is an effective method of rehydration for children. Just as with most things, Gatorade is perfectly healthy when consumed in moderation for the average person. Based on the research we did, we can say that Gatorade, and other sports drinks, are in fact a better form of hydration than just water for trained athletes over long periods of time. However, for most people who drink it after their 30 minute gym session twice a week, it likely holds very little if any benefit over water; as they do not lose the same amount of carbohydrates and electrolytes as trained athletes.

Questions to consider:

- What duty does Gatorade have to tell people about sugar levels?

- How would you design a study to try and prove that Gatorade is not necessary for the “average joe”?

- Would athletes competing in certain sports benefit more from consuming Gatorade than others similar to creatine and why might this be?

References

- “Thirst Quencher Product Details.” Gatorade, the Sports Fuel Company, Stokely-Van Camp Inc. , 2018, www.gatorade.com/product/2014124?size=24-pack.

- Urso, C., Brucculeri, S., & Caimi, G. (2014). Physiopathological, Epidemiological, Clinical and Therapeutic Aspects of Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 3(4), 1258–1275. http://doi.org/10.3390/jcm3041258

- Marathon runners with hyponatremia

- Popkin, B. M., D’Anci, K. E., & Rosenberg, I. H. (2010). Water, Hydration and Health. Nutrition Reviews, 68(8), 439–458. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2908954/

- Importance of staying hydrated

- Dehydration rates and rehydration efficacy of water and sports drink during one hour of moderate intensity exercise in well-trained flatwater kayakers. Ann Acad Medicine Singapore. http://www.annals.edu.sg/pdf/37VolNo4Apr2008/V37N4p261.pdf

- Trained athletes were able to rehydrate better with gatorade than with water after a long workout. However, neither option was able to completely rehydrate the athlete.

- Malik, V. S., Popkin, B. M., Bray, G. A., Després, J.-P., & Hu, F. B. (2010). Sugar Sweetened Beverages, Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease risk. Circulation, 121(11), 1356–1364. http://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.876185

- Sugar sweetened beverages are linked with type 2 diabetes, obesity

- Committee on Nutrition and the Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Sports drinks and energy drinks for children and adolescents: are they appropriate? Pediatrics. 2011;127:1182–1189. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/127/6/1182

- They concluded that small amounts of sports drinks could be appropriate for young people participating in vigorous physical activity in hot, humid weather. However, for the average young athlete, sports drinks are unnecessary and could contribute to negative health outcomes, such as excess weight gain and tooth decay

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/fivehanks/6138640703 (image)

I think they’re should be more information about how Gatorade is only really needed when working out at a high intensity for long periods of time. Perhaps it could be sold mostly at sports nutrition stores or put a more informative label on the bottle. Endurance athletes (like marathon runners, triathlon competitors, etc.) are probably the group that actually needs the benefits Gatorade can provide. Since they are pushing themselves for such a long period of time, the body doesn’t have time to replenish the necessary carbohydrates and electrolytes. They are just ingesting what they need instead of excess. Gatorade could also be beneficial during preseason, or a time when practice or exercise goes all day.

A study could be conducted with the “average joe” by having them do their regular workout while drinking Gatorade, and another group drinking just water. After completion, their blood sugar levels could be measured and compared. An endurance athlete group doing their workout could be used for comparison to the “average joe” groups. Researchers could also measure their blood sodium levels before, during, and after exercise to prove that in the endurance case, they are just replacing what they lose and in the “average joe” case they may be consuming excess.

Thanks for taking the time to read and comment! I like your ideas on adding a more informative label to the bottle. It seems like regulations are making it required to have more in-depth nutritional information, but in this case it seems like that information should also be supplemented with a small written explanation.

I think a study definitely needs to be done with the ‘average joe’ population, one should get a variety of age brackets as well to see how Gatorade’s effects may be different depending on age. One would need to take the blood sugar and sodium levels at the start and end of the work out to see how they compare to each other as well as give half the group plain water and one group Gatorade. This way we could see if Gatorade is more beneficial to a mid-40’s participant than a teenage participant, which would also give us an idea of just how much rehydration is necessary as one ages. Another interesting study I would like to see in professional trained athletes would be comparing how Gatorade effectively rehydrated in different training programs, for example you could have a bodybuilder compete for an hour and an endurance runner run a race in an hour and give them both Gatorade and compare rehydration levels!

It would be interesting to see a study on normal people who drink Gatorade on the regular. As someone who drinks Gatorade even when not working out, I would be interested to know what harm I am doing to my body by drinking Gatorade because I like to believe Gatorade is better for you than something like soda. It would also be very interesting to know at what intensity of exercise is drinking Gatorade acceptable. Would someone doing a weight-lifting workout benefit from Gatorade or is Gatorade more tailored to long duration low intensity athletes?