Charles Milton Bell (1848-1893) and Studio, William McKinley, c.1877-1891, 2001.0017.0007, The Baltimore Collection, University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press.

Browsing through the Baltimore Collection, one stumbles upon an unexpected sitter. Presenting his right profile, clad in an elegant costume and standup collar, his hair combed to the side, William McKinley (1843-1901), the future 25th President of the United States, is shown in bust-length, looking away.

The portrait is not unknown: it is one of the multiple period reprints of a photograph taken by Charles Milton Bell (1848-1893) in his Washington, D.C. studio, sometime between 1877 and 1891. McKinley, a rising U.S. representative from Ohio with national ambitions, posed for Bell and his assistants on more than one occasion, as illustrated in the C. M. Bell Studio Collection of glass negatives at the Library of Congress. Bell’s skylighted studio at 459/465 Pennsylvania Avenue NW was an attractive venue for congresspeople like McKinley, eager to craft a polished image of leadership for themselves. [1] This desire accounts for the fact that, during one photographic session in the early 1880s, McKinley and Bell tried no less than thirteen different poses, some seated, some standing. [2] One of these would eventually be selected as the matrix for the mass reproduction and circulation of McKinley’s likeness.

Charles Milton Bell (1848-1893) and Studio, William McKinley, c.1877-1891, LC-B5- 950228, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

The presence of the latter portrait within the Baltimore Collection interrogates the logic of representation for White and Black sitters in late-19th-century America, yet also the very processes of collection management, data creation, and interpretation in archival institutions. The Baltimore Collection did not form a coherent ensemble before its donation to the University of Delaware. A handful of White sitters, therefore, now belong to a group where most sitters appear to be Black. Through archival accessioning, William McKinley, a figure of White authority, finds himself in dialogue with individuals he likely not associated with during his lifetime. The Bell portrait questions both the role of the archive in constructing identities and the interweaving narratives of identity construction of various sitters at the time that photograph was disseminated. Though McKinley’s profile was likely not intended to survive as part of the group it now belongs to, this is one of the locations where it will endure.

When McKinley arrived in Washington, D.C. in the fall of 1877 from Canton, Ohio, where he had been practicing the law, the U.S. was reeling from a hotly contested presidential election and the so-called Reconstruction era was nearing its end. In the wake of uncertain results, Democratic candidate Samuel J. Tilden negotiated a compromise with Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes: Tilden would yield the presidency to Hayes on the condition that Republicans withdraw all federal troops still stationed in the South. [3] The informal arrangement also mandated Southern legislatures to deal with the situation of emancipated African Americans, without interference from the federal government. Motivated by political maneuvers, the compromise spelled the end of Black political enfranchisement in Southern states and the dawn of what would be known as “Jim Crow laws”.

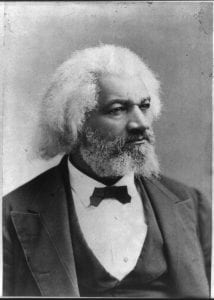

Charles Milton Bell (1848-1893) and Studio, Frederick Douglass, 1881, LC-USZ62-19288, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Back in Washington, D.C., the rising Black middle- and upper-class, whose commercial activities continued booming throughout the 1880s and 1890s, likely looked down on the situation with appalled eyes. Fueled by migrations of African Americans from the South, cities like the nation’s capital counted a growing fraction of enriched Black entrepreneurs, eager to play their part in a new urban bourgeoisie. [4] Charles Bell captured their likenesses in great number. Next to customers like William McKinley, the studio recorded the faces of innumerous Black and indigenous individuals whose names are still known to this day. Within the Bell portfolio, writer and abolitionist Frederick Douglass (1881) and chief Red Cloud (Maȟpíya Lúta) of the Oglala-Dakota (1880) survive alongside U.S. President Chester A. Arthur (1882) and women’s rights activist Susan B. Anthony (1891). The Bell negatives, preserved together at the Library of Congress, create a prosopography of late-19th-century D.C., its interpersonal exchanges, its networks and absences of networks. Here too, the Bell collection confers a fictitious yet convincing collective identity on its thousands of sitters.

Along the northeastern coast, thousands of African Americans in D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, Atlantic City, or New York flocked to studios like that of Charles Bell to immortalize their prosperity and social standing. In these spaces, they crossed paths with sitters like William McKinley, likely aware of the diversity of customers welcomed to pose for the camera there. McKinley would likely not have been disturbed by it. His own positions were ambiguous, yet generally favorable to African American rights. [5] He opposed voter suppression in the South, although his appeals to Black constituencies were often motivated by political calculus. During his six terms in Congress, his Ohio district was gerrymandered by Democrats with the hope he may be unseated. However, and despite these attempts, McKinley steered clear of direct attacks on Southern state governments.

“The new President delivering his inaugural address [March 4, 1897],” LC-USZ62-237, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

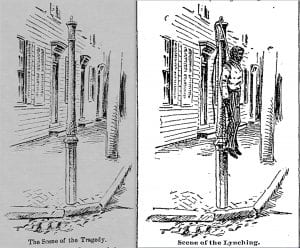

How did the Black sitters of the Bell and UD Baltimore collections react to the news of atrocious acts of lynching? Did some of them have family or friendship connections in Alexandria? Business partners perhaps? Even after the deaths of both Charles Bell and William McKinley (assassinated in September 1901), D.C. studios continued to portray seemingly well-to-do, happy Black families, dressed to the nines and commanding respect. Consciously or unconsciously, their dignified image produced another kind of discourse by offering an alternative to a widespread imagery of disfigured and slain Black bodies.

C. M. Bell Studio, Rev. J. A. Johnson and his Family, c.1901-1903, LC-DIG-bellcm-12424, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

In the space of photographic salons, the parallel reality of violence and discrimination in the United States seemed to be veiled, and administrations like McKinley’s failed to prevent it from existing. Such mixed fortunes account for the president’s conflictual image in collective memory. On February 28, 2019, a bronze statue of McKinley was torn down in Arcata, California, after concerns were voiced about the imperialist and racist stances of his administration. [10] The move divided the community. But McKinley fell.

Although it is tempting to read an object like McKinley’s portrait by Bell in light of its current repository at the University of Delaware, by assuming, for example, that some African American sitters or viewers may have actively wanted its presence there, one should thus be wary of ascribing a collective identity to a collection identified as such only recently. White and Black sitters in the U.S. Northeast did not face the same challenges when asking for their portrait to be taken. Their image did not endure in a similar way, and these contests for memorial persistence endure in today’s archive. In this instance, Charles Bell’s portrait of a young congressman McKinley retains its individuality as an aside, simultaneously within and next to its companion items, sharing their history yet incapable of sharing it at the same time. Here, for once, the White male sitter is the outlier.

[1] On the history of the Charles Bell studio, see Kathleen Collins, Washingtoniana Photographs: Collections in the Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1989), 14-22.

[2] “C. M .Bell Studio Collection,” Library of Congress: Prints & Photographs Online Catalog, accessed April 13, 2021, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/search/?q=bellcm&st=gallery.

[3] On the compromise of 1877, see C. Vann Woodward, Reunion and Reaction: The Compromise of 1877 and the End of Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 1966); Michael Les Benedict, “Southern Democrats in the Crisis of 1876-1877: A Reconsideration of Reunion and Reaction,” The Journal of Southern History 46, no. 4 (November 1980): 489-524; Roy Jr. Morris, Fraud of the Century: Rutherford B. Hayes, Samuel Tilden, and the Stolen Election of 1876 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007); Michael A. Bellesiles, 1877: America’s Year of Living Violently (New York: The New Press, 2010). The most important and comprehensive studies of the Reconstruction era remain Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 2014 [1988]) and Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction (New York: Knopf, 2013 [2005]).

[4] On this subject, see Jacqueline M. Moore, Leading the Race: The Transformation of the Black Elite in the Nation’s Capital, 1880-1920 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999); Elizabeth Clark-Lewis, First Freed: Washington, D.C. in the Emancipation Era (Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 2002); Kate Masur, An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle over Equality in Washington, D.C. (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010); Elizabeth Dowling Taylor, The Original Black Elite: Daniel Murray and the Story of a Forgotten Era (New York: Harper Collins, 2017).

[5] McKinley’s positions on race have been reexamined in Benjamin R. Justesen, Forgotten Legacy: William McKinley, George Henry White, and the Struggle for Black Equality (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2020). The best generalist biography of McKinley remains H. Wayne Morgan, William McKinley and His America (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1998 [1963]).

[6] “Lynchings must not be tolerated in a great and civilized country like the United States; courts, not mobs, must execute the penalties of the law. The preservation of public order, the right of discussion, the integrity of courts, and the orderly administration of justice must continue forever the rock of safety upon which our Government securely rests.” First Inaugural Address of William McKinley, March 4, 1897, in Speeches and Addresses of William McKinley, From March 1, 1897 to May 30, 1900 (New York: Doubleday, 1900), 9.

[7] Letter from Republican Senator Shelby Moore Cullom, introducing Ida Wells Barnett to President William McKinley, March 19, 1898. Year Files, 1884-1903, General Records of the Department of Justice, Record Group 60, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[8] Archibald Henry Grimké and the Colored National League, Open Letter to President McKinley (Boston: Self-published, 1899).

[9] William F. Brundage, Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880-1930 (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 155. See also James E. Hall, “‘Draw Him Up, Boys’: A Historical Review of Lynching Coverage in Select Virginia Newspapers, 1880-1900,” in Words at War: The Civil War and American Journalism, eds. David B. Sachsman, S. Kittrell Rushing and Roy Morris Jr. (West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press, 2008), 377-388.

[10] Bill Disbrow, “Arcata removes controversial McKinley statue that stood for century after surviving 1906 SF quake,” SFGate, February 28, 2019, https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/humboldt-statue-controversy-removed-13653140.php.