Figure 1-3: Portraits of unidentified women and a man taken at the Parlor Gallery, likely in the 1880s and 1890s (Accession #s 2001.0017.0001; 2001.0017.0017; 2001.0017.0003). The Baltimore Collection, University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press.

Have you ever had your photograph professionally taken in a photography studio? Do you remember the excitement or the anxiety of receiving a small, rectangular likeness of yourself that you could hold in your hand? It is likely that the patrons of the Parlor Gallery located on South Ninth Street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania had those same feelings of excitement, pride, or anxiety when they had their picture taken in the late nineteenth-century.

Figure 4: 1875 GM Hopkins Philadelphia Atlas. Free Library of Philadelphia, Map Collection. Courtesy of PhilaGeoHistory.org.

The Parlor Gallery, operating during the 1880s, was located in a brick building near the corner of Ninth and South Streets in Philadelphia. Prior to its operation, the Samuel L. Smedley 1862 Philadelphia Atlas showed the land as the site of the Colored Presbyterian Church and grounds. The church building, dating from 1846, still exists today but was renovated into a single family residence in 2010.[1] By the 1875 G.M. Hopkins Philadelphia Atlas brick rowhouses populated the land, built to house residences and businesses. The photography studio at the address of 523 and 525 was one of the business that occupied buildings on the neighborhood block. Today, in 2017, 525 S. Ninth Street remains as the corner house on the block. It is a 5-bay wide, three-story brick façade building, unlike the standard 2 bay-wide buildings adjacent to it. The current building is a multi-family residence at 5,258 square feet and was built in 1920. [2]

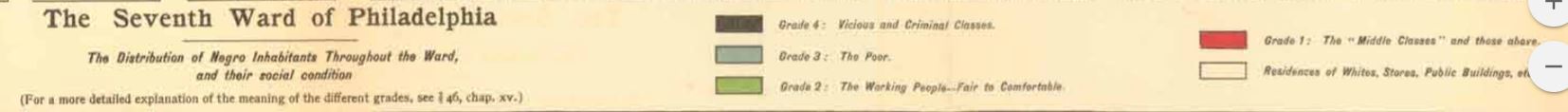

Figure 5: Detail of Map of the Seventh Ward + Legend from “The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study” and “Race and Class in Du Bois’ Seventh Ward”

Given the address of the studio in nineteenth century Philadelphia, it is likely that this location was a site of interracial business activity. The studio was located in the Seventh Ward of the city of Philadelphia, which in 1890 had the largest population of Black residents in the city. According to W.E.B. Du Bois in his seminal study, The Philadelphia Negro, the area surrounding the photography studio, the Seventh Ward, was multi-racial with the inclusion of “some of the best Negro families of the ward.” [3] The Black families of this area were of upper, middle, and working-class status. Nearly all of them were born in Philadelphia. According to the map of the Seventh Ward featured in Du Bois’s study, the neighborhood block where the Parlor Gallery was located was home to three middle or upper-class Black families (highlighted in red on the map above). The Parlor Gallery building itself is listed as a “Residences of Whites, Stores, Public buildings, etc.” [4] Given that the photographs with the inscription of the Parlor Gallery from the Baltimore Collection and the Library Company of Philadelphia thus far have been photographs of people of African descent, this was a White-owned business receptive of the needs of their Black neighbors.

The Parlor Gallery was one of several photography studios under the management of photographer, Lewis Horning during his long career as a photographer. [5] The Parlor Gallery is listed in business and city directories between 1884 and 1889. From 1884 and 1887 city directories list the Parlor Gallery at the address of 523 S. Ninth Street, Horning’s home address and five to six other photography related businesses. [6]

Figure 6: Louisa A. White photograph album [graphic], c.1878, Accession # P.9505. Courtesy of Library Company of Philadelphia Digital Collections

The Parlor Gallery is where Black residents of Philadelphia visited to have a likeness of themselves printed for public viewing for prosperity and to share with others. The payment of portraits, the crafting of self-presentation and self-possession was a tactic used by many to assert citizenship, demonstrate success in life, and at the same time consciously or unconsciously subvert negative depictions (or portrayals) of Black people featured in caricatures, racist literature, and scientific racism studies. By the end of the nineteenth century the democratic nature and economy of photographs allowed people of all economic stratas to partake in the activity. “The Baltimore Collection” contains three photographs of unidentified Black people, two women and one man, who visited the Parlor Gallery to have their picture taken. The Parlor Gallery located in a neighborhood filled with elite Black people in the city could have been ‘the place to go’ by Black people to have your picture taken. Who were these individuals? Could they have put on their “Sunday best” then walked out of a house across the street or around the corner from the Parlor Gallery to have their picture taken? Could it be possible to breathe life back into the people who look out at us in these photographs? Who were they? Their names? Their life’s work? Their loved ones? Their friends? Is there anything to learn from them as we still grapple with racist depictions of Black people in our society today? Future work could include mining the archives for names and any family records of the Black families who lived in the neighborhood around the photography studio. Happy digging!

By: Kelli Coles

Works Cited

[1] Inc, Zillow. “832-836 Lombard St, Philadelphia, PA 19147 | Zillow.” Accessed November 29, 2017. https://www.zillow.com:443/homedetails/832-836-Lombard-St-Philadelphia-PA-19147/90197812_zpid/.

[2] “525 S 9th St, Philadelphia, PA,” Redfin, accessed November 15, 2017, https://www.redfin.com/PA/Philadelphia/525-S-9th-St-19147/home/38172241.

[3] W. E. B. Du Bois, The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study (New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 2007), 60.

[4] W. E. B Du Bois, The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study (New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 2007), 37-38.

[5] He also owned photography studios named Union Photographic Rooms and City Photograph Rooms during his forty plus year career according to the Linda A. Ries and Jay W. Ruby, Directory of Pennsylvania Photographers 1839-1900, Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission, 1999.

[6] The Library Company of Philadelphia also has several early 1880s photographs which have the 523 S. Ninth Street address in the inscription on the bottom recto side of the mount. The other studio locations include 1320 Chestnut Street, 56 N. 8th Street, 63 N. 8th Street, 1109 Market Street, 120 S. 2nd Street, and 202 S. 2nd Street. However, I am unsure of the names these locations. The online resource site, Langdon Road, lists the location of 56 N. 8th Street as L. Horning’s Photographic Rooms. This site includes cartes de visites from the 1860s with this location stamped or inscribed. Overall, L. Horning or Lewis Horning is listed as proprietor of the photography studios. At this time I relate this to be the same person due to his presence in the city and business directories of the era and the Directory of Pennsylvania Photographers listed above.

[7] “Housework [Advertisement for Parlor Gallery],” The Philadelphia Inquirer, February 2, 1900, Friday morning edition, America’s Historical Newspaper.