“We depend on images to give substance, if not meaning, to the fleeting moments of our life. A world without photographic images is almost inconceivable.”– Susan Sontag

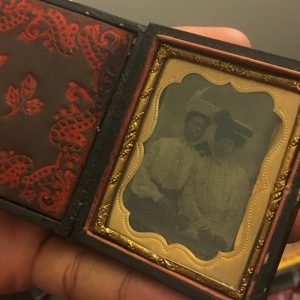

[Portrait of an unidentified woman wearing a dress with leg-of-mutton sleeves], Accession number 2001.0017.0044, The Baltimore Collection, University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press.

Many of my memories and the memories people have of me are paired with some sort of photographic evidence. Growing up in a house where there was a camera on every table gave me an experiential education on how to preserve life. This interest in documenting life was only increased by my first camera phone; a Sprint flip phone with 3 or 4 megapixels that I shared with my older siblings. Not having anyone to call, I was quick to document our trips to the mall and rides to my grandmother’s house. Those formative years making images would push me to make stylistic collections and establish my own archive of friends and family during my teen. Since then, I’ve found myself heavily dedicated to preserving memories and piecing together untold stories of people’s experiences. Therefore, when I was first learned of The Baltimore Collection in March of 2017 during my visit to the University of Delaware, I was elated about the prospect of researching African American’s photographic habits, patterns, and resources during the 19th Century.

When the Porter family donated a box of images in 2001 to University of Delaware, I don’t think anticipated a team of grad students would be researching them 16 years later. Over the past 15 weeks, we as a class have collaborated, researched, and had countless discussions about the future of this collection. Partnering with the faculty in the Library, Special Collections and Department of Art Conservation to further our understanding of how best to publicize this collection. We have debated the importance of the work we’ve been doing and questioned the institutional integrity. We have reached substantial milestones, establishing Metadata for 53 images, collaborating in groups to discuss the … With the help of Dr. Debra Hess Norris, Amber Kehoe, and Jan Broske, we were able to discern the materiality of the collection, sorting through descriptions of tintypes, albumen, matte collodion, silver gelatin printing-out prints (POP), silver gelatin developing-out prints (DOP) and halftones. This was the 1st time that we were able to handle the photos, seeing them in person completely changed my understanding of what we were looking at. Colors appeared to be more vivid, the damage was obvious, and the materiality was discernable.

My position on photographic restoration has changed considerable amounts during the duration of this project, while I used to believe that it was a profession steeped in high-culture and Victorian pretension, my onion rapidly transformed. Key to this transformation was the lecture given by Dr. Debra Hess Norris of the University of Delaware’s Historical Conservation department. Norris was one of the few professors to let her passion for the work materialize within her lecture. Her dedication to photo restoration reinstated the value of the work that we’re doing with the Baltimore Collection and introduced me to the profound influence photo preservation can have on public memory. Norris was interested in the significance of photographic collections and how preservation may impact cultural heritage. An emotional investment to the work is often overlooked, Norris introduced us to a number of projects that highlighted the impact of natural and manmade emergencies, underscoring the vulnerability of historical documentation and need for this training. Although we haven’t been heavily focused on the physical restoration of the project, our class has made a significant impact on how these images could be used when furthering a historical understanding of Black life in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States.

Out of all the texts that were assigned in the class, the one that was most influential may have been Ross Kelbaugh’s Introduction to African American Photographs: 1840-1950. Kelbaugh uses his collection of African American photography to teach the history of image creation. The collection is impressive, I often found his narrative problematic and his passion for “owning people” somewhat distasteful. However, the good thing about the book is that it is an instruction guide on how to find, purchase and sell your own vintage images. Which led me to purchase my own Tintype. I too, hope to establish a collection, that will hopefully be able to expand narrative of African American history.

[Photograph of an unidentified woman and an unidentified child on a porch], The Baltimore Collection, Accession number 2001.0017.0031, University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press.

As we come to a close with this phase of the collection, I am so excited to see it’s completion, but I hope that additional people will take the opportunity to expand on this work further. In January, the Art Conservation department has plans to perform additional labor to preserve the collection. It will be difficult to share the images because the ArtStor is private, but if we are to share the WordPress those interested in 19th-century photography have the opportunity to learn more.

Heart Shaped Follicle on [Photograph of an unidentified woman and an unidentified child on a porch] – magnified to 120X via. Carson MM 300

The future of the collection is truly endless, but I know that bureaucratic diplomacy within the neoliberal institution will surely subdue the process of knowledge production. However, once most of the doors are opened I could see an exhibit in collaboration with the Special Collections department, pairing undergraduate classes with the images to learn more about black migration, collaborations with the State and Local History Association. There’s also the possibility of collaborating with the Colored Conventions Project to see if any of these people or photo studios have overlapping events. Lastly, and my favorite option we take it one step further and dedicate large amounts of funding and time to identify all of the people in the collection, making it a priority of the University to grow and change the scholarship on Black lives and history in the Mid-Atlantic and the role of photographs and self-fashioning (portraiture) have therein.