If the practice of art history has taught me anything it’s that sometimes it’s okay to stare. Stare at pictures, stare at words, stare at people.

I often find myself trying to connect deeper to people through eye contact. It’s an important aspect to human connection. In order to fully connect to visual things, I find it best to stare until you find something that interests you. This practice carried on into this semester-long project. My initial instinct when I first got to look at the pictures in the ‘Black Portrait Photograph Collection’ was to try to find an unobstructed view of the subjects’ faces. For many, this was a difficult task. At this moment countless questions raced through my head.

What did they look like?

Were they staring at the lens or at the photographer?

What was their family like?

Did they like getting their picture taken?

Were they happy?

The photographs were full of so many lives, personalities, and stories. This is where my true connection to the future of these photographs began. Previously, I never liked to extensively look at photographs of Black faces from this time. All I remember seeing is images of violence and grief. I remember their given derogatory names and bigoted descriptions. I remember their anguish, their pain, their suffering, their complicated roles. But these portraits would be the exception. They weren’t inherently violent. They weren’t inherently melancholic. They weren’t inherently anything but portraits of people that look like me.

So I sat there with wide unwavering eyes, staring into the faces of those subjects, trying to find something to grasp onto and pull into my present.

How many of their hopes and dreams lived on?

How did they die?

Were they able to experience love and loss?

What was their definition of Blackness?

Did they even care?

Has the livelihood of our people really changed over time?

Now, sitting here, weeks after I was first introduced to them, these photographs take on new meaning. Their message lives on in the multifaceted presence of Black identity today. We still struggle with cementing our own space. We still grapple with having accurate representation in the mainstream. We still are looking to define ourselves. But now we have our own methods to get there. Access to photography has come a long way over the last two centuries. We’re out there- taking photographs of ourselves; trying to craft our own image, our own futures. To carry on through the hardship and adversity of Black existence is to remember those who came before you; carry their hopes and dreams, and grant them space to grow beside you. Securing space for these images to live and breathe has never been more important.

So how can I, as a young Black scholar, connect to these portraits of those who are no longer here?

By seeing them.

By remembering them.

By carrying them with me.

In the end all I can do is promise to maintain that eye contact.

Eyes always open,

Looking straight ahead into our collective future.

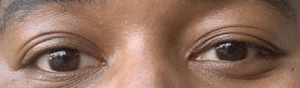

Figure 1. Leah Mackall. Untitled. 2021. Digital Photograph. Image courtesy of Leah Mackall.

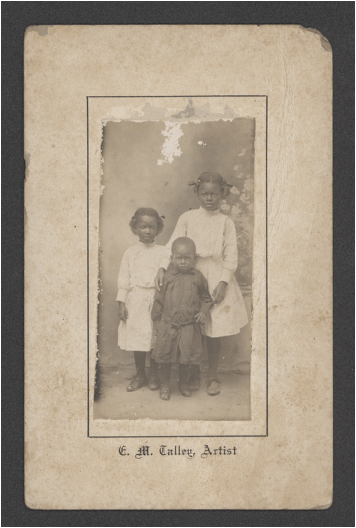

Figure 2. Portrait of three children, including Mary. ca 1180-1910. Cabinet card. Image courtesy of University of Delaware Special Collections.

Figure 3. Portrait of two women standing and two men seated. ca 1880-1910. Cabinet card. Image courtesy of University of Delaware Special Collections.

Figure 4. Devin Allen. Untitled, from “A Beautiful Ghetto” series. 2015. Chromogenic color print. 20” x 30”. Image courtesy of the Studio Museum in Harlem.