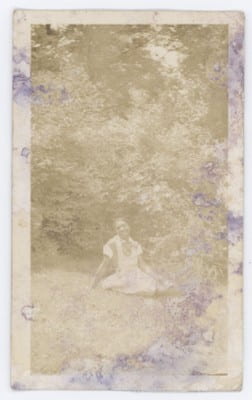

Perhaps unexpectedly, various landscapes appear throughout the University of Delaware Baltimore Collection of portrait photographs. Sprinkled here and there, some are real, some are fake. Some were likely lush green, some others grey. And some, even, are fading away. Across time and locations, the sitters featured in the collection interact with landscapes and inhabit them. Whether the flat painted vistas of studio backgrounds, the streets of unidentified cities, or the manicured lawn of a park or backyard, the individuals portrayed here embrace landscape in all its forms. At the very least, their presence in the landscape manifests a powerful agency to reclaim spaces and imagine themselves into a world shaped by White racism.

[Portrait of an unidentified young woman outdoors, seated in the grass near a wooded landscape], 2001.0017.0028, The Baltimore Collection, University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press.

This joyful pose offers a welcome contrast to the interaction between Black sitters and landscapes as often depicted in American portraits and visual culture since the 18th century. In the colonial era, Black figures mostly occupied the margins of the frame, inhabiting the landscape of their own enslavement, deprived of names and identities. America’s nature, burdened by slavery and reshaped by commercial expansion, was a landscape of suffering.

John Hesselius (1728-1778), Charles Calvert and [his slave], 1761, oil on canvas, Baltimore Museum of Art, on display at the Maryland State House, Annapolis.

In the early 19th century, Black portraits outside of environments of enslavement often retreated indoors. Though Black individuals started being depicted in their individuality and not as mere types, the realm of the image still shut them out of a wider social world, enclosing them in indoor poses with neutral backgrounds, in undetermined settings. The White gaze, artist or audience, seemed unwilling to comprehend a Black individuality evolving freely in public spaces, the same spaces it dominated economically, politically, and culturally. This separation led to what art historian Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw has described as “the trope of the black body […] used in an alternate mode as a prop to establish the identities of the colonizing bodies that sought to control it. [1]”

Notable exceptions include Nathaniel Jocelyn’s famous portrait of Joseph Cinqué [Sengbe Pieh] (1839), leader of the rebellion on board the slave ship Amistad, and William Matthew Prior’s portrait of Nancy Lawson (1843), where a glimpse of landscape is caught through a window, almost masked by drapes.

Photography initially reprised the formulas tried out by portrait painting. Yet the neutral, uniform backdrop of the first daguerreotypes soon gave way to the use of cloth wall coverings, suggesting an opening. This, in turn, triggered the resort to painted landscapes as surrogates for the world beyond, unsuitable to the needs for control (and long exposure time) of studio photography. Paradoxically, the propped landscapes of portrait photography became a way for most African American sitters to reinvest spheres many of them had long been excluded from. While White artists often reinserted emancipated enslaved people into landscapes through the means of aestheticization, nostalgia, and patronizing sentimentality (see, for instance, Winslow Homer’s Watermelon Boys from 1876), photographic landscapes allowed for a new sense of projection of blackness, despite the occasional mawkishness.

Here, I would like to dwell on the portrait of a woman seated in front of such a backdrop. Her pose is self-assured. Wearing an elegant dress, with her hair combed into a bun, she looks directly at the camera.

[Portrait of an unidentified seated woman in front of a painted backdrop], 1860-1880, 2001.0017.0045, The Baltimore Collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press.

[Studio portrait of an unidentified seated woman in front of Capitol Building backdrop], 1918-1930, 2001.0017.0038, The Baltimore Collection, University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press.

Turning the inside into the outside, such photographs opened the horizon of the studio to open up black imagery beyond the walls of portraiture and the invisible yet palpable barriers of racial discourses. Though many pictures in the Baltimore Collection accomplish this goal, others hint at the fragility of one’s status, and at the dangers of oblivion. A counterpoint to the portrait-landscape that opened this text, a second picture presents another narrative of nature.

[Portrait of an unidentified young woman outdoors, seated in the grass near a birdbath], 1900-1950, 2001.0017.0029c, The Baltimore Collection, University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press.

[1] Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, Portraits of a People: Picturing African Americans in the Nineteenth Century (Andover, Massachusetts: Addison Gallery of American Art, 2006), 17.