Men’s, women’s, boys’, and girls’. Anyone who has ever shopped at a clothing store is familiar with the typical categories these shops contain, with aisles clearly demarcating the different sections like traffic-filled streets on a city street plan. Yet how many of us always stay in our own lane?

Though I identify as a woman, my closet is full of clothing pieces I’ve found in all corners of my favorite stores. Silky blouses and structured dresses from the “women’s section” of Loft or T.J. Maxx and cozy, oversized sweaters and flannels from the “men’s section” of Old Navy or Goodwill. Yet whenever I deviate from shopping in my “designated” zone, I sense a creeping feeling that I’m somehow breaking the rules of shopping, that I’m doing something wrong.

Evidently, fashion brands have caught on to this feeling in the past several years, as some brands have done away with gender categories on their websites and in their stores entirely. Catwalks and red carpets have also bore witness to more androgynous fashions in recent years, with men in skirts and women in suits becoming more and more common. Yet no testing of the gender binary comes without protest; over the past several years, angry posters have repeatedly taken to the web to express their distaste for these androgynous styles, seeing their growing popularity as a calculated move by the so-called modern “transgender agenda.”

But exactly how modern is gender non-conformance? With all the strides that have been made in gender equality in the United States, with more and more people embracing gender identities that defy the limits of the male/female binary, many Americans still seem to view androgynous fashion as a fad embraced by younger generations like Gen Z and Gen Alpha. People have always just dressed like a man or a woman, right? Why can’t we too?

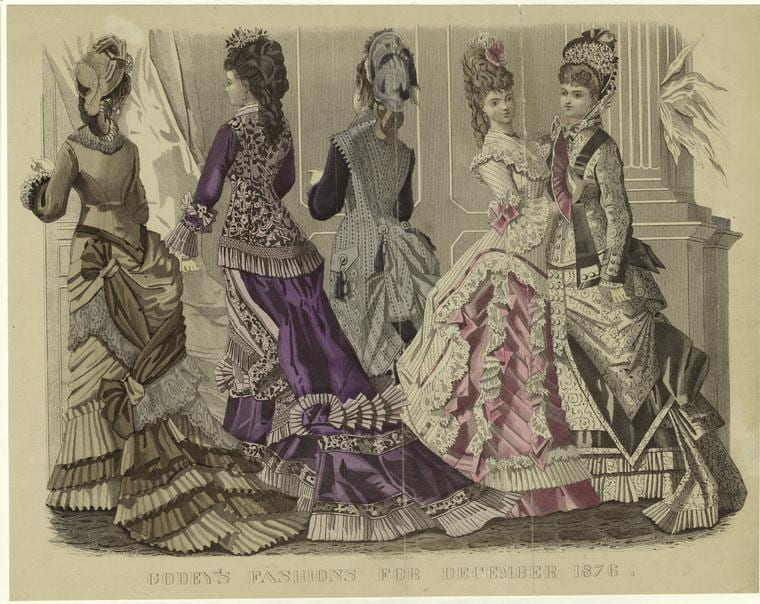

Historic photographs, however, complicate this notion. While photographs throughout history show many people who adhered to contemporary gender roles, they also depict those who went against the grain, challenging the acceptable attire of their time. “Portrait of a woman, possibly Ellen Hopsons,” likely taken sometime between 1890 and 1910, is one of these such photographs. Contemporary late-nineteenth century women’s fashion was hyper feminine, with fashion plates from this time boasting outfits with nipped waists, frilly lace, high bustles, and full skirts.

Yet the attire depicted in this photo is unmistakably different from these precedents. In “Portrait of a woman, possibly Ellen Hopsons,” the subject, who appears to be a Black woman, stands tall, her gaze leveled at the camera. She wears two classic elements of menswear, a white button down shirt and a striped, satin bow tie, and her legs are adorned with not a bustled skirt, but rather a long, black trouser skirt.

This outfit undoubtedly embraces androgyny, with its clear allusions to contemporary menswear. Yet this fashion style was actually fairly common at this time for progressive, young women. This style of fashion appears to reference the ideals of what contemporary writers in the early twentieth century referred to as the movement for the “New Woman.” The term, first coined by Irish writer Sarah Grand in 1894, describes the archetypal model of the young, liberated woman of the new twentieth century who rejected standard nineteenth century gender norms, embracing instead more egalitarian, feminist forms of living and style. Depictions of young women smoking, riding bicycles, and engaging in otherwise “masculine” behaviors permeated the visual culture of the early twentieth century, achieving the height of their fame in Charles Dana Gibson’s iconic “Gibson Girl.” Throughout these depictions, two items of clothing repeatedly appear: those being the white button down shirt and the trouser skirt, both of which are worn by the subject of “Portrait of a woman, possibly Ellen Hopsons.” Women who ascribed to the “New Woman” style adopted the white button down shirt as a unisex item that emphasized the role of working women with its utilitarian connotations, while their acceptance of trousers skirts or “divided skirts” demonstrated yet another favor for androgynous attire.

“Portrait of a woman, possibly Ellen Hopsons” exists as wonderful evidence of not only Black women’s participation in the New Woman movement, but also as an affirmation of their contribution to and engagement with the long history of androgynous fashion. In the midst of a mainstream society that seeks to invalidate the experiences of androgynous and nonbinary people, especially those of people of color, historical sources such as this demonstrate that gendered fashion has always been a contentious ground for all sorts of people, a site of exploration and boundary pushing for countless individuals throughout history.

If you’d like to learn more about “Portrait of a woman, possibly Ellen Hopsons,” click here to read Leah Mackall’s post, Will it be Enough?