When photographs enter into an archive with no research or story attached to them, in what ethical ways can we recover those stories? This a question that is constantly at the forefront when delving into the history of marginalized groups. An essay titled Venus in Two Acts, by Saidiya Hartman raised questions pertaining to how we should recover Black stories. To provide some background on the essay, Hartman relays the story of Venus, a figure in the archive of slavery. She is described as being a dead girl due to a ship captain being responsible for killing two young black women, herself being one of them. No one remembered her name or recorded anything that she said, this seems to be a repeated fate for many enslaved people. There are hundreds of stories similar to Venus, and the only stories left standing relate to violence. [1]

Why are the small portions of their life that are shared only accounted to violence in the archives? It is more than likely that there is an abundance of information related to the captain’s history, a man that committed a horrific crime. Venus’ history was not recorded because of the racial hierarchies that were in full effect. Many folks at the time had the thought process in which Venus was an inferior being, and no one would care to explore her story at a later date. This was a disheartening time in American history.

Our question now is, how do we give a voice to folks like Venus? One way is to create a narrative for these silenced voices, but this solution comes with complications. We will never know exactly what happened in the lives of folks like Venus, therefore we don’t want to make up or fabricate a narrative. There is really no way we can resuscitate her story, even if we placed our own imagined narrative into the archive. I believe we should leave her story as is, as heartbreaking as that is. The archives should mirror the events that occurred in the past to the best of their ability. I do not think it would be the right decision to place our own conceptions into the past.

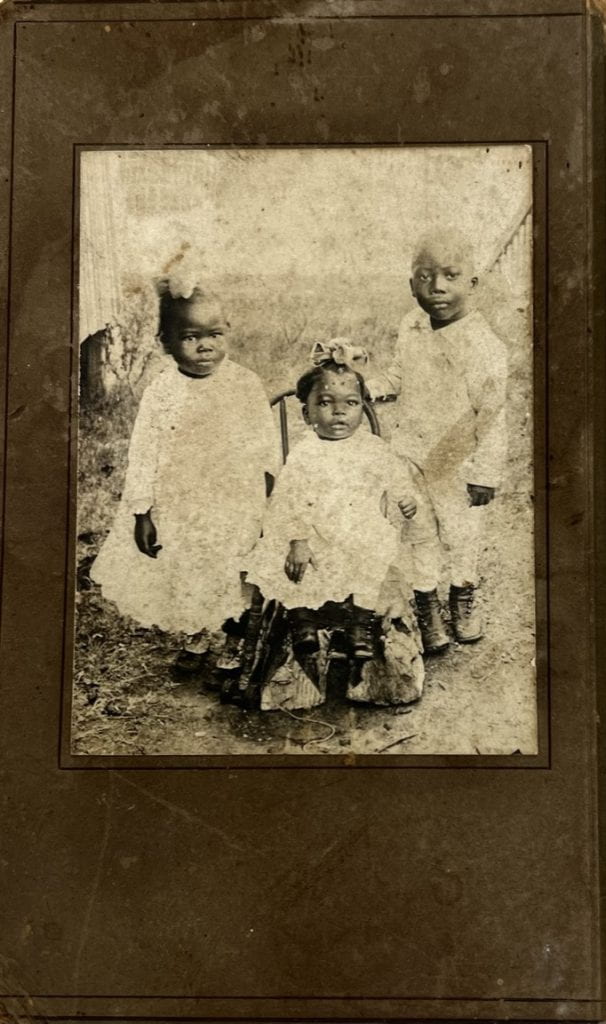

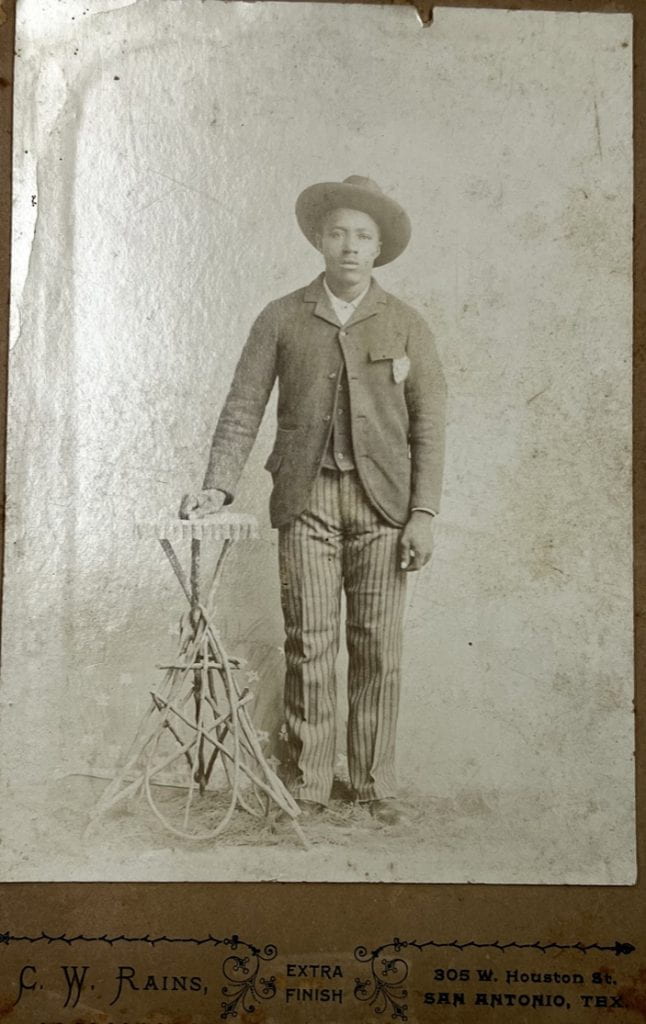

The University of Delaware acquired the Black Portrait Photograph Collection with little to no research attached to the objects. The folks in which Hartman describes predates the folks in the Black Portrait Photograph Collection. The Black Portrait Photograph Collection includes figures from many years later who were not enslaved. However, they still are fighting the same battle — the stories of all these folks are not recorded, making it difficult for others to discover them. Students, including myself, with help from faculty members were assigned to the task in which they would research these photographs and create metadata in order for them to be digitized. When researching, I found myself running into dead ends, with not many answers to my questions. At times I found myself using my best judgment to make assumptions in order to write the description of the photograph. This work can raise similar concerns to the ones Hartman brings up in relation to Venus. On one hand, the metadata I have created allows them to be digitized, making them discoverable for future researchers to utilize and expand upon. On the other hand, who knows if the sitters in the photographs even wanted to be discoverable to broad audiences. What if my interpretation of the photograph is completely different from what the sitters in the photographs had in mind?

It’s a difficult task to retell stories that have been lost, ones such as Venus and the sitters in the Black Portrait Photograph Collection. The photographs in the Black Portrait Photograph Collection were once someone’s personal belongings, how do we know if they wanted to be put on display? The memories of these folks should very much live on, but who has the authority to tell their stories?

Figure 1, Portrait of three children, possibly the children of Johnnie and Ellen Young, circa 1880-1910, Cabinet Card. From Black Portrait Photograph Collection.

Figure 2, Portrait of a man standing, wearing a hat and striped trousers, circa 1880-1910, Cabinet Card. From Black Portrait Photograph Collection.

Endnotes:

- Hartman, S. (2008). Venus in Two acts. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism, 12(2), 1–14.

- Figure 1, Portrait of three children, possibly the children of Johnnie and Ellen Young, circa 1880-1910, Cabinet Card. From Black Portrait Photograph Collection

- Figure 2, Portrait of a man standing, wearing a hat and striped trousers, circa 1880-1910, Cabinet Card. From Black Portrait Photograph Collection