As a graduate student pursuing a doctoral degree in History, I often feel my life is a repetitive cycle of reading, responding to emails, attending to homework, and tackling the mountain of laundry that is generated daily in my household. Sometimes, during the hustle and bustle of the semester, I find that the only way to accomplish my homework and maintain a tidy household is to listen to my assignments as I wash, dry, and fold clothing before putting it away. It’s a rhythmic life with constant motion that keeps me grounded and mindful of the labor required to maintain a home. A clean house is important to me. Coming home to an organized space is calming and reminds me of the houses my mother and grandmother kept. Although some days I feel that a storm has ripped through my home as schoolwork takes priority over chores, I also see cleaning as a family tradition.

Cleaning and, more particularly, doing laundry are something I have always seen as part of family time. To provide you with some necessary context, my grandparents’ house is immaculate. When I stayed with them as a child, I recall enjoying pancake breakfasts at the kitchen table while my Nana vacuumed before we headed to the hospital where she worked as a nurse for decades. In the afternoon, Nana would make lunch and place me on a mat over her pristine carpet while she vacuumed again. Similarly, growing up, I watched my Granddaddy meticulously clean counters and kitchen surfaces after every meal he cooked. When they came to visit us, we would play and then watch movies while they cleaned and knocked out laundry. Their daughter, my mother, similarly always seems to be cleaning her way about the house. Many a weekend as a child I joyfully spent lying on the bed or the floor of my mother’s bedroom watching rom-coms as we sorted and folded laundry.

These personal family memories bubbled to the surface this semester as I worked to piece together what little information I could find about three young children in the University of Delaware’s Black Portrait Collection. One child’s portrait had the name “Little Frank Wilkerson” on the back, which allowed me to tentatively attach this image to a real boy who was the son of Etta Wilkerson, who census records and city directories between 1900 and 1920 variously described as a cook, washerwoman, and farmer. In 1940, the census takers documented Etta Wilkerson as living with her grandchildren and daughter, Thelma Keaton, who was employed as a laundress. Other boys represented in this collection of images were not so easily followed in the archive of papers and government documents, though. On the same day, I reached into a folder to withdraw an image of a young Franklin Wilkerson, I encountered two other traces of children in the archive whose names I am not sure will ever be recovered.

One image of another child in a white dress with a close-shaved haircut sitting on a posing stool with their mouth held agape is difficult to identify. No inscriptions or photographer’s imprints are there to guide a researcher in narrowing down who they might be. The lack of leads is infuriating for a researcher attempting to create metadata to make this image discoverable for any family members who might know this child and the life they grew up to lead. However, it is not inappropriate to surmise that this child was loved and cherished. The very survival of this image suggests that people have cared for this portrait and, perhaps at one point, could recall the child’s name and the spaces they occupied.

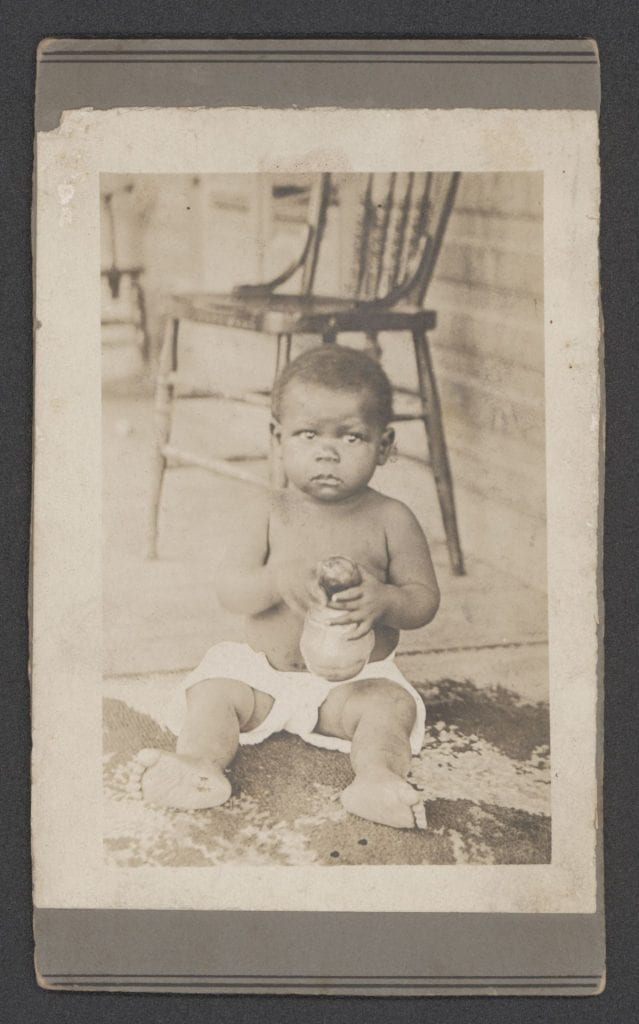

Another image I encountered, of a toddler-aged child sitting on a rug with an object in their hands, does give us some information. On the back of the image, handwriting that has worn and rubbed over the years has rendered it difficult to read. However, playing with exposure and light levels on a TIF file scan of the photo in Adobe Photoshop helps see the inscription that isn’t visible to the naked eye. It uplifts a partial transcription of the note that reads, “[t]o Grandmama from Edie / did you get your money Monday that papa sent / [two illegible words or markings] / to D[illegible] Sarah Johnson.” To the left of the note, there is also an address that seems to read “702 Leal St.”1 This brief amount of information opens up its own chain of questioning and demonstrates how the portrait of this child is an object with dual purposes as a visual image and a medium for correspondence between family members. However, searching census records for Sarah Johnson is less fruitful than looking for Franklin Wilkerson. Her name is more common. A quick search of records from San Antonio, as well as most of the materials in this group of photos are thought to be from, reveals multiple Sarah Johnsons listed as Negro laundresses living in San Antonio between 1900 and 1920. Presumably there were Sarah Johnsons working in a similar trade in the 1880s and 1890s as well.

Knowing this possible connection makes me wonder if this young person could be another child of a laundress. Was the child in the other portrait that was unmarked also the child of a laundress? Is the letter writer’s Grandmama the person who received all of these images? Was Grandmama, too, a domestic laborer and mother who loved her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren like Etta Wilkerson did over the course of her lifetime? What would that mean within this collection? And what did these women wish for their children when they arranged for these images to be taken? These photographs and their stifling silences can only tell us so much within this archival setting. They leave these young souls frozen in the potential image of what their mothers hoped could have been. Importantly, though, they also enable us to imagine these women in their multitudes as they self-fashioned their families and commissioned images that add to the history of laundresses as consumers, collectors, and empowered agents influencing material culture.

Stumbling upon these images sparked a desire to know the women who arranged them. Looking at the images of these children, I wondered how these visual objects likely commissioned and circulated by Black women figured into their efforts to carve out space for themselves and their families to make meaningful lives. If the mothers of all of these young people were washerwomen, how did their participation in producing and consuming photography that evidenced their self-fashioning play into longer histories of women who took in laundry acting as “cultural brokers across various scales of community interaction.”2 I was curious to understand how these images could be situated in the narratives of Black washerwomen’s labor in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Though they remain underrepresented in historical discourse, scholars from across disciplines in the social sciences have studied and written about the critical roles washerwomen have played in American society. Much of the scholarship available focuses on Civil War Era interactions when Black women served on army bases laundering servicemen’s uniforms and later urban environments where Black washerwomen staged labor movements. Authors like Katrina Eichner have discussed how washerwomen functioned in the Texan frontier at places like Fort Davis after the Civil War, and she emphasizes how this labor afforded Black women a level of independence to set their own hours and engage in other economic pursuits.3 Other historians, like Crystal N. Feimster, have elaborated on the vulnerable situations of Black laundresses during the Civil War period as their work for both the Confederate and Union armies extended labor systems of the Old South that exposed women to sexual assault.4 Many scholars in various fields, including Jessica Edwards and Josie Walwema, have taken the time to contextualize the revolutionary actions of the Washerwomen’s Association of Atlanta, whose strike in 1881 organized an interracial network of washerwomen and Black ministries to advocate and establish a uniform rate of $1 per dozen pounds of laundry, which was influential on later labor movements of the twentieth century.5

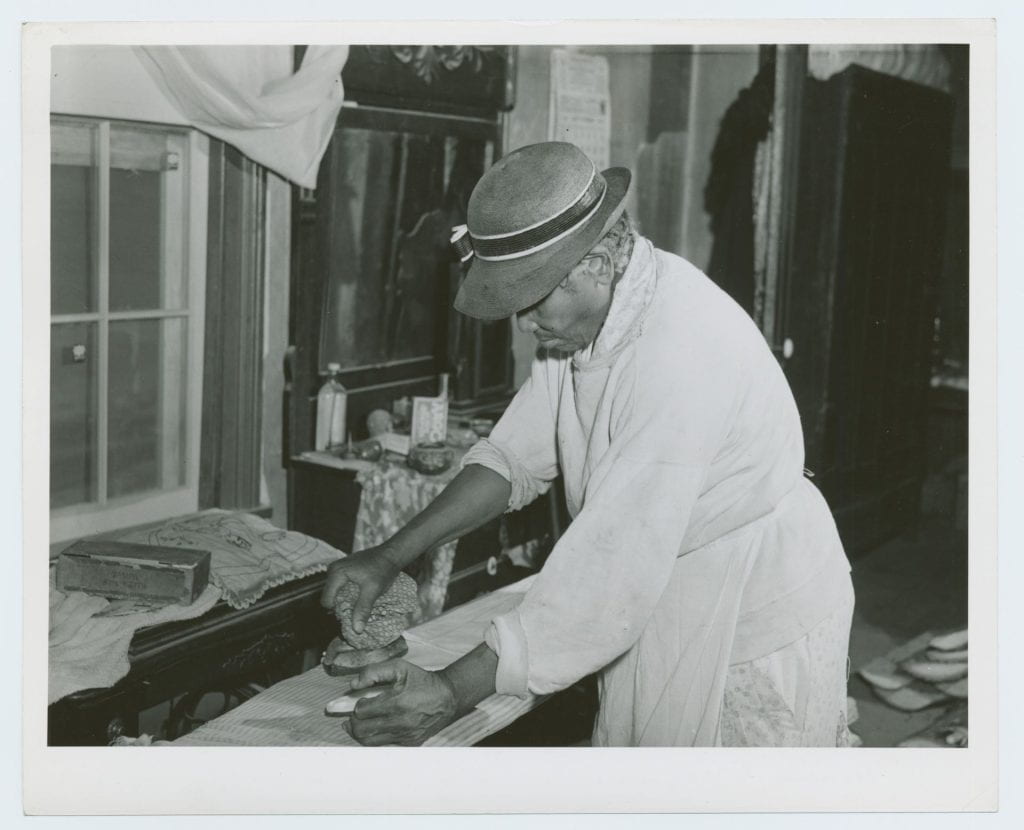

The existing scholarship paints a vivid picture of Black women’s labor as laundresses that saw them handling dangerous chemicals like lye and crossing racial spaces to conduct their business. The successful strike led by the Washerwomen’s Association of Atlanta and other historical events where laundresses challenged racism and sexism is a reminder of the quotidian resistance and labor organizing of Black women that are often neglected in American history. Visual culture plays an important part in these narratives. Vernacular photography and paintings capturing working Black women freezes them in time. Their presentation is curious and troublesome as it prompts a viewer to consider how these women felt about the image and what agency they had in the production of it. This genre of visual art featuring Black laundresses is an invitation to see the hidden forms of resistance and daily spontaneous actions that Robin D.G. Kelley illustrates in his essay “‘We Are Not What We Seem’: Rethinking Black Working-Class Opposition in the Jim Crow South.”6 Searching for the subaltern infrapolitics of Black women laundresses can change the way we these so-called occupational portraits are viewed. The images can be read as hidden transcripts resurfacing the evasive actions and self-fashioning of Black women that created space for redefining themselves while exercising underrecognized power amidst the oppressive structures of the Jim Crow age.

This thinking leads back to the images of Franklin Wilkerson and the other two young children who possibly grew up surrounded by women who took in laundry, which enabled them to have greater control over their labor and work environments while raising children. The potential network of laundresses associated with these children’s portraits also resurfaces the communal actions of laundresses in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. As Eichner points out, archaeological studies have long established that laundresses banded together in tackling washing, cooking, and child-rearing tasks to care for one another. The actions of mothers sewing dresses for their children, drawing upon their earnings to pay for a photograph, and jotting a note to a family member or friend is inseparable from the visual presentation of these images. For me, these objects reanimate the social lives of Texan laundresses and aid in re-focusing how they created space for themselves and their children to imagine other possibilities that resisted the confining limitations of Jim Crow laws. These extant photographs that Black laundry workers consumed, collected, and circulated are symbolic of their dignity, autonomy, and daily resistance.

Imagining the possible lifeworlds and social networks of Etta Wilkerson and Sarah Johnson is a powerful exercise that refocuses the agency and activities of Black women as laborers, heads of households, and mothers raising children in turbulent times. Thinking of their self-fashioning through photography and their strength reminded me of my own great-grandmother, Esther Barnes Martin, who worked as a domestic caring for white families’ homes in Harlan, Kentucky, and later Cleveland, Ohio. After her husband George died in a car accident, only months after she and her children migrated north to Cleveland in 1957, she was left alone to raise five of their eight children who were still living at home with the help of her mother, Della Mae Fitts. Peering at these portraits and thinking about my own family history, I found myself curious about how these women saw the world. I also found myself wondering how these images of unidentified children could be considered part of the shadow archive of self-empowered laundresses and domestics who raised generations of children while working to build a more equitable society through their networks, society affiliations, and involvement in local churches. The photographs became a challenge to see Black women’s reimagining and resistance at play in these visual objects. The pictures became personal as I thought of how my family fit into this archive as well. Researching Etta Wilkerson brought me closer to Esther as I considered her self-fashioning after the death of her husband and the portrait she sat for alongside her children in the aftermath. I pondered the photos she arranged of her children and the ones she kept of her children and grandchildren. Perusing the possibilities of these portraits from the University of Delaware’s Black Portrait Collection poignantly reminded me of the family rituals of cleaning and the love that Black women give to their children that enables them to pursue new possibilities. The labor of Black women working as washerwomen and laundresses, as these photos suggest, is the foundation for so many Black families and generations of growth.

Notes

- Leal Street is a road in San Antonio. Searches on real estate websites like Zillow list a home at 702 Leal Street that was built in 1946, likely years after this photo correspondence was sent.

- Katrina C. L. Eichner, “Frontier Intermediaries: Army Laundresses at Fort Davis, Texas,” Historical Archaeology 53, no. 1 (March 2019): 138.

- Eichner, “Frontier Imediaries,” 142.

- Crystal N. Feimster, “Rape and Mutiny at Fort Jackson: Black Laundresses Testify in Civil War Louisiana,” Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas 19, no. 1 (March 2022): 11-31.

- Jessica Edwards and Josie Walwema, “Black Women Imagining and Realizing Liberated Futures,” Technical Communication Quarterly 31 no. 3 (April 2022): 245-262.

- Robin D.G. Kellley, “‘We Are Not What We Seem’: Rethinking Black Working-Class Opposition in the Jim Crow South,” The Journal of American History 80, no. 1 (June 1993): 75-112.