The bright flash of a light bulb, the chafe of a stiff collar, the quiet clink of glass plates. What would the sitters of this portrait photograph have seen, felt, heard, and smelt when this photo was taken?

A few weeks ago, I found myself walking down the streets of Philadelphia, carefully avoiding the slowly-growing puddles accumulating on the ground from the day’s heavy rain. I was on my way to Jinxed, a thrift shop and community hub in South Philly, where I had signed up for a tintype portrait session with photographer Jeff Howlett. On the twenty minute walk there (I was committed to finding free parking) I fussed over my outfit, carefully shielding my dress from the rain with my umbrella and worrying that the humidity would cause my hair to frizz. To top off this theatrical production, I also happened to be carrying a large, ornate sword.

In an age where one can take 30 selfies in the bathroom mirror to find the “perfect” one to post online, I have found myself fascinated by older methods of photography, particularly those that require one take, like tintypes. I suppose this is what attracted me to tintype portraits, a medium that demands the exposure of a single shot onto a wet glass plate, no take backs, no redos. Yet the risk of this one-take wonder also inspired stress in me – what would I wear? Should I bring any props? What if I stain my dress on the way there? After all, I was paying $60 for a single photo!

Upon entering the store, I was pointed to a back room, where the tintype artist had set up a popup studio, complete with a backdrop, posing chair, lights, and, of course, a camera. I waited my turn, watching the client in front of me as she carefully arranged her hair, using her own phone camera as a sort of mirror. I noticed how she steadied herself on the tall chair, carefully laying her hands over her lap in a gesture of orchestrated ease. When the crucial moment came, the photo was over in an instant, punctuated by a sharp flash of light and the crisp sound of the shutter. As quickly as it had begun, the client hopped off the chair, thanked the photographer, and shuffled to the side to patiently wait for the photo to be developed, another agonizing wait. Had it come out clearly? Was it to her liking? And, the dreaded question, had she blinked?

While witnessing this exciting display, it occurred to me that while everything I had just witnessed had gone into the making of a single photo, the vast majority of that time was not represented in the photograph itself. While I had witnessed the hair arranging, the posing, the thanking, and the waiting, the only remnant of this experience depicted in the photo was a single instant, a moment forever frozen in time.

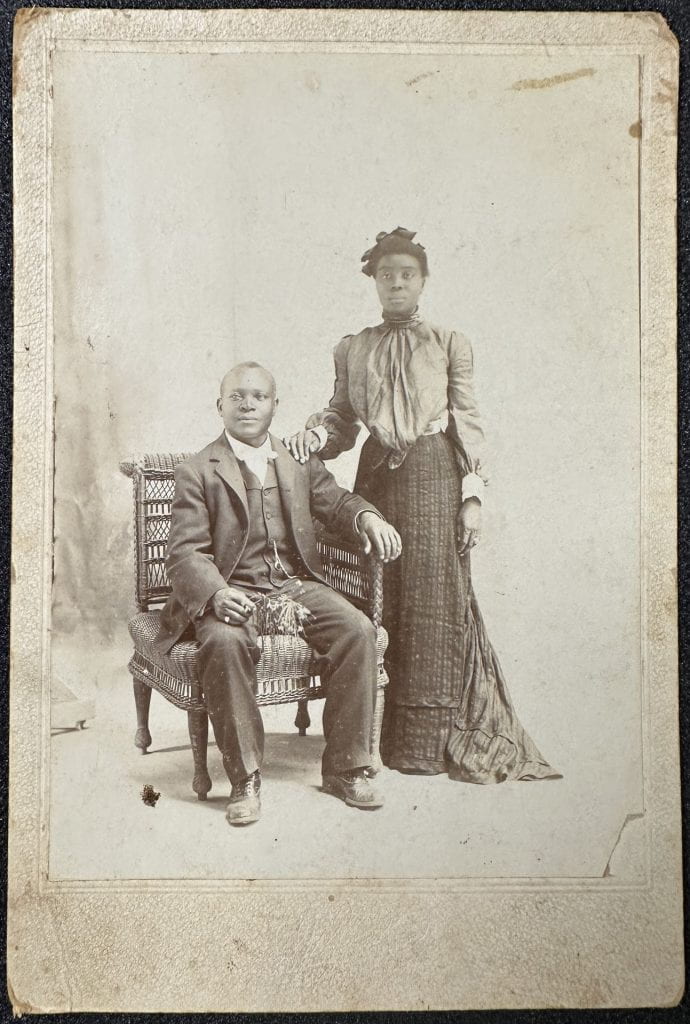

This experience has since prompted me to see historic photographs, such as “Portrait of a man and a woman,” likely taken at the turn of the twentieth century, in an entirely new light. While it is easy to view this photograph today as a single moment, for these two subjects it was much more. For them, the making of this photograph may have been an entire afternoon, perhaps even a day, of selecting outfits, traveling to the studio, waiting patiently for their turn, deciding on a pose, and waiting nervously, once again, to see if the image had come out to their liking. What thoughts ran through their minds before, during, and after this photo was taken? What sort of conversations did they have? Did they decide on their pose beforehand, or was it a spring of the moment decision?

With only the visual record of this photo to go off of, answering these questions feels impossible, yet perhaps it is not entirely so. While the “behind-the-scenes” qualities of portrait photographs may not be immediately apparent, some argue there is a way to reach them, to imagine the moments that surrounded these frozen points in time. Scholar of photography Tina Campt calls the invisible aspects of such photographs “frequencies,” using the metaphor of sound to explore the implicit histories and stories these portraits hold, imagining what life may have been like for the figures depicted.1 Such a framework challenges the way we view historic photographs today, prompting us to move beyond the confines of the 2D image to consider the historical, contextual, and even emotional qualities of these photographs.

For me, using Campt’s idea of frequencies to imagine the surrounding context of this photograph helps me to connect with the figures depicted, moving beyond the orchestrated nature of their postures to the human moments that surrounded – a joke shared between the two subjects, perhaps, or a moment of celebration upon seeing the image for the first time.

In the same way, my favorite parts of my own portrait are not what is visible, but rather all the things you can’t see: how I had to balance the tip of the sword on my toe to have it at the right height, how I fussed over my outfit on the walk to the studio, hurriedly waving my dress to dry the few raindrops that had managed to wet it. I think about how my choice of prop references my fifteen years of experience as a competitive fencer, and I wonder in turn what the desert willow the man holds in “Portrait of a man and a woman” symbolized for the pair.

While we will likely never know for sure what exactly happened when this photograph was taken, imagining these moments, hearing their frequencies, feels far from futile. If anything, it provides a deeper, richer context to this photograph, as purposeful an act as hopping over puddles in the rain.

Citations

- Campt, Tina. Listening to Images. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017.