The University of Delaware has acquired nine tintype and two crayon enlargement photographs that have been grouped together and titled the Black Portrait Photograph Collection (BPP). The photographs were purchased for their historical significance, without the pertinent information of the authoring photographer(s), where they were produced, or the dates of their production. Each photograph in the collection is a portrait, depicting one or several sitters we cannot name, and the full extent of each photograph’s provenance is unknown. The compelling power of portrait photography is its intrinsic “call and response” quality. The posed sitters, we assume, have offered us a glimpse of who they are. Across time and space, they “call” out to us with their postures, their facial expressions, and with their fashion. Our first instinct may be to identify and categorize the sitter(s) −is the sitter interesting, baffling, or beautiful? We call the gender, age, class, and nationality of the sitter(s) into question as we pull from our own previous knowledge to discover who this person was.

The hand-colored portrait of a woman in a black dress is a crayon enlargement photograph that depicts the full body view of an unidentified Black woman standing in a studio setting. The setting features a potted, flowering green plant and a large bay window that looks out unto abstract greenery and the blue sky. Her body is positioned at an angle with her left foot in front of her right, her left hand is resting at waist height against a window seat or possibly on her waist, and her right hand is resting at shoulder height against the windowsill. Her face is tilted toward her right, while her eyes gaze directly at the camera. Her skin is rendered in grayscale with hints of brown and pink. She is dressed in a mid-length black dress with a white lace collar, white sash tied at the waist, and short scalloped sleeves. Through the fashionable length of the sitter’s dress, the lack of jewelry, and the flowering scenery, we can begin to speculate her age, class, marital status, and more, but it does not tell us who she is, her name, or what led to her portrait being taken.

Portrait of a woman; Date: circa 1860-1880; Material: Tintypes; Collection: UD Library: Black Portrait Photograph Collection

The anonymity of the sitter(s) and the lack of biographical information on the photographs featured in the Black Portrait Photograph Collection make it easier to look beyond the image and analyze the photographs as physical objects that are rich with material information. The nine tintypes and two crayon enlargements are not just the images they depict; they are the materialized results of scientific and technological processes that allow for the transcription of images on material, such as metal and paper. Regardless of the image’s legibility, photographs take up space, are weighty, tactile, and lustrous. Ranging in scale, some photographs are produced to fit in the palm of a hand −protected behind the clasp of an ornate case− and others are large and intended to be handled. While some methods of photography allow an image to be reproduced, the photographs featured in the collection are singular objects that are vulnerable to time and the elements. They have oxidized, faded, and amassed the everyday wear and tear damage of being used and circulated.

The shift from personal belonging to circulating commodity is what enabled the University of Delaware to purchase the photographs featured in the Black Portrait Photograph Collection. We can speculate that the photographs were created for personal reasons and originally belonged to people who knew the sitter(s), if not the sitter(s) themselves. Through time, the circulation of the photographs, from owner to owner, has obscured the information and value that comes from initial intent and sentiment, leaving the photographs to exist outside of their original context. The shift from personal object to commodity, from commodity to preserved artifact, impacts how the photographs have been used, preserved, and what they mean over time. Their value in today’s market comes from their dignified depictions of what is assumed to be Black people and their survival as artifacts that illustrate the techniques of early image making.

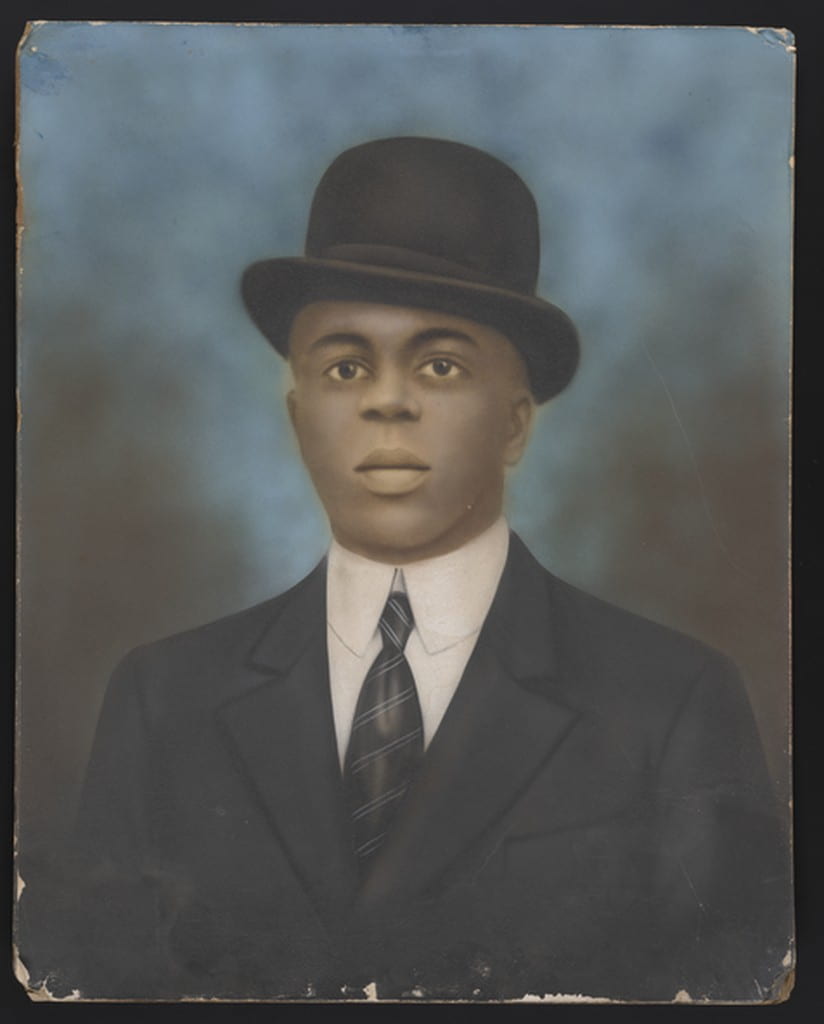

There are two distinct methods of photography represented in the collection. Nine of the photographs are tintypes, collodion images on japanned iron, that we speculate could have been produced as early as 1860 and as late as 1880. These malleable, thin, rectangular iron objects exist today in various conditions, but still depict discernable portraits of various people. On the surface of these objects are dents, creases, and folds. All but one was purchased without a frame, exposing the folded or clipped corners of the tintypes. Thick black borders are visible along the outer edges of some of the tintypes, suggesting that they were either intended to be framed or possibly were framed at some point in their history. The remaining two photographs in the collection are hand-colored crayon enlargements of which the hand-colored portrait of a woman in a black dress is one. We speculate the portrait was produced in the 1920s, as this technique fell from popularity by 1930. Much larger than the tintypes (9 x 12 inches), this rectangular image is imposed on paper for secondary support.

Crayon enlargement, circa 1920s. Crayon Enlargement (Detail)

GRA 0140, Black Portrait Photograph Collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library, Newark, Delaware.

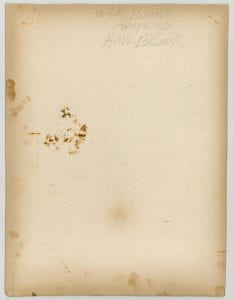

The portrait of the woman in a black dress can be read, not only by the state of its condition, but also for the skill and creativity of the artist’s rendering. This technique of image making was prone to flaw, blur, and fading, so the images were retouched with crayons and paints (Albright, Gary E. & Michael K. Lee. “A Short Review of Crayon Enlargements: History, Technique, and Treatment.” Topics in Photographic Preservation 3 (1989): 28-36). Still vivid with color, the hand-colored photograph bears surface abrasions, creases, and scratches, most visibly along the outer edges of the paper. This may be due to how the photograph was displayed, possibly within an album held in place with adhesive. Her black kitten heel shoes have buckled straps and have been possibly accented with pencil. There is also a luster effect on the black of the dress that contrasts with the matt surface of the rest of the photograph. There are some white markings on the right border and near the shoes of the image. On the back of the photograph is a handwritten note detailing coloring instructions for the figure. The cursive reads, “med Brown makeup, Hair Black.” The written note raises the question of how the sitter may have requested to be rendered, as well as revealing the technological processes of making a hand-colored portrait.

Hand-colored portrait of a woman (Verso)

Though the biographical information on the hand-colored portrait of a woman in a black dress is limited, we can assume that this woman was an autonomous person, and that this portrait may have been her way of “calling” out to us across time and space to assert her personhood. Engaging innovative methods of analysis, I want to speculate a full life for the image and the physical photograph as well, revealing the full spectrum of possibility. Historical context gathered from research paired with scholar Saidiya Hartman’s method of critical fabulation enable us to center this woman’s humanity and attempt narrating a life for her based on the clues found in the photograph (Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1-14). The hand-written note on the back of the photograph reminds us that these same methods of analysis could be used on material aspects of the photograph as well. Who wrote this note, was it the photographer or the woman? How many of the creases, folds, and dents in the portrait’s surface came, not from neglect, but from care? What if this object, well preserved for about one hundred years, spent its existence cherished and loved by its various owners? What if this portrait is just one of dozens of images this woman had made of herself, not significant enough for the family photo album?

The preciousness of the photographs in the Black Portrait Photograph Collection are not only in their survival as a marvel of technology, but also in their embodying of human relations.