On December 7, 1941 the Japanese launched a surprise attack on the United States Naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. This would be the final straw that would drag them into the conflict that had consumed much of the rest of the world, World War II. One of the major opponents to the United States during World War II was the Japanese Empire. Due to fears of disloyalty, the U.S. government enacted a plan that would have a profound impact on many facets of Japanese American lives, the forced relocation of all Japanese on the West Coast to internment camps. One aspect of their lives that this impacted was their ethnic identification. For some people the embarrassment and humiliation of being forcibly relocated and detained just because of their race would lead them away from Americanization, the assimilation into American culture, and identify more with their Japanese roots. For others, in a somewhat ironic way, the internment experience led them to prove their loyalty and “Americanism” in different ways. In both cases age played a large factor in determining which way they would go with their ethnic identification. So in effect the relocation and internment of Japanese Americans led to the development of two ethnic identifications with age playing a determining factor in which identification developed.

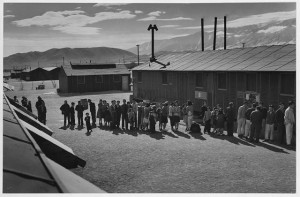

The humiliating experience of being rounded up and forced to live in internment camps left many Japanese with a negative view of the United States. Even after the forced relocation many Japanese were subjected even more humiliations. An example of this are the famous loyalty questions that every internee ages 17 and older were asked in order to determine who was loyal and disloyal.[1] The most infamous of these questions were questions 27 and 28. Question 27 asked, “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States, wherever ordered?”[2] Question 28 asked, “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance of obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power or organization?”[3] These questions were used to gauge the loyalty of the Japanese Americans to the United States. Because of the anger and resentment of having their loyalty questioned some answered no to both. Those that did were branded as disloyal by the government and moved to the higher security camp at Tule Lake.[4] Not only were Japanese Americans subjected to the humiliation of forced relocation and questions of their loyalty but they also had to live in the terrible conditions of the internment camps. These conditions were captured in photos by Ansel Adams and figures 1 and 2 effectively show some of the terrible conditions that they had to experience.

Fig. 1 Ansel Adams. Mess line, noon, Manzanar Relocation Center, California. Library of Congress, 1943, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppprs.00368/?co=manz

Fig. 2 Ansel Adams. Roy Takeno, editor, and group reading paper in front of office, ManzanarbRelocation Center, California. Library of Congress, 1943, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002696016/resource/

For example both show the worn out buildings that they had to live in as well as the fact that the camps were located in isolated, harsh desert areas.[5] [6] Figure 1 also shows the lack of privacy that Japanese Americans were forced to endure at the camps such as having everyone eat together in mess halls instead of privately at home.[7] Some of the other harsh conditions not shown in photos that they had to live with were things like no running water in their apartments, only some places had electricity and heat, and no air conditioning in the summer.[8] Living with these stresses helped lead some groups to identify more with their Japanese heritage. For example, for Japanese Americans at Tule Lake their culture became part of a way to view and interpret their situation.[9] Some Japanese ghost stories, such as the hitodama, which centered on omens and death, started to appear more and circulate rapidly.[10] Also, stories of animal spirits and possession such as kitsune-tsuki, fox-possession, began appearing more during internment.[11] One last example is stories of ninjitsu started gaining popularity during the internment period due to the similarity between the main themes of those stories, unfair suffering and revenge, and the experience and desires that the Japanese Americans had while being interned.[12] While stress from the situation was one cause of Japanese Americans connecting with their Japanese roots it was not the only one. Another cause for this ethnic identification was due to the fact that after being relocated to the camps the Japanese Americans were now living in a community where they were the only ethnic group.[13] This in turn led people to act more Japanese by doing things such as improving their ability with Japanese language.[14] So when combined, both the stress of the situation that the Japanese Americans had been put through as well as the fact that they had been relocated to predominately Japanese communities led to some groups increasing identification with their Japanese heritage.

While the forced relocation and internment caused some Japanese Americans to reconnect with their Japanese roots and form a Japanese ethnic identity it also, ironically, encouraged others to try to gain more acceptance as Americans. One way that they tried to gain acceptance was by utilizing their citizenship and the court system.[15] During the internment process there were quite a few Japanese Americans who tried to use these to have the relocation and internment deemed unconstitutional and illegal. A perfect example of this is the Korematsu v. U.S. (1944) court case.[16] In the case the U.S. was challenged on the legality and constitutionalism of the forced relocation and imprisonment of Japanese citizens based on race.[17] Unfortunately the court would go on to rule in favor of the United States.[18] However, this case as well as similar cases such as Gordon Hirabayashi v. U.S. (1943) and Minoru Yasui v. U.S. (1943), shows how Japanese Americans tried to show their Americanism by utilizing their citizenship and the court of law.[19] On the other hand some Japanese Americans took a little more direct route to prove their loyalty and Americanism by enlisting in the military. The Japanese Americans that enlisted were all put into one regiment, the 442nd Combat Regiment Team, which would go on to become one of the most decorated military units.[20] Many of them saw this as an opportunity to prove their loyalty to the United States and be considered Americans. One example of this was George “Montana” Oiye, a Japanese American who fought in the 442nd during World War II.[21] He attempted to enlist multiple times before he finally succeeded and joined the 442nd. [22] After enlisting he would go on to fight in battles throughout Europe and eventually earned a bronze star for his bravery.[23] He did all of this while his sister was imprisoned at an internment back in the country that he was fighting for.[24] There is a bit of irony to the fact that, like George Oiye, many Japanese Americans who were fighting to free Europe from an oppressive dictator likely were imprisoned or had family that were imprisoned by the country they were fighting for. However, as shown in figure 3, many of them hoped to show how loyal they were to their country precisely because they had family imprisoned in those camps.

Fig. 3 Photographer Unknown. It’s “Present arms!” for members of the 442nd Combat Team, Japanese-Americanfighting unit, as they salute their country’s flag in a brief review held the day of their arrival at Camp Shelby, Miss. Library of Congress, June 1943, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3c27108/

These two different methods that Japanese Americans used to try to show their Americanism, military service and the judicial system, show that in a way internment spurred some Japanese Americans to trying to become more American.

One last interesting thing to note is how age could impact how the internment process affected Japanese American ethnic identity. Internment effected the older, Issei generation differently in comparison to the younger, Nisei generation. For example, in both Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and George Takei’s autobiographies, they talk about how since they were children when they were interred they did not feel the full effects of the internment experience and thus did not have as much resentment as their parents did.[25] Another example of the differences between the impacts that internment had on the younger generation versus the older generation is Lane Hirabayashi’s analysis of the story “The Sensei.” In the analysis he notes how the younger and generally more adaptable generation was able to do well in adjusting after the internment process.[26] However they did this by repressing some memories of their past and adopting a “model minority” moniker.[27] This would allow them to be better accepted as Americans. On the other hand the older generation which was less able to adapt had a much more negative experience as a result of internment.[28] Both of these examples show the difference between how each generation was impacted by the internment experience. This tended to direct the younger generation more towards Americanization while the older generation leaned more toward their Japanese roots.

In the end how did internment impact Japanese Americans’ ethnic identity? For some internment led them to reconnect with their Japanese roots because of the pressure of the situation and being forced into a larger group of other Japanese Americans. For others, it encouraged them to prove their Americanism through court battles or military service. One other thing that had an impact on how internment affected Japanese Americans’ ethnic identification was there age. Younger generations were better able to cope with the internment experience in comparison to the older generation. No matter which direction they went the Japanese Americans who were imprisoned at internment camps during World War II had the development of their ethnic identity impacted in some way by the experience.

[1] Rosalyn Tonai. “A Short History of the Japanese American Experience”. U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal. English Supplement, no. 2. 34, accessed November 4, 2015.

[2] Tonai, “A Short History,” 34.

[3] Tonai, “A Short History,” 34.

[4] Tonai, “A Short History,” 34.

[5] Ansel Adams. Mess line, noon, Manzanar Relocation Center, California. 1943. Ansel Adams’s Photographs of Japanese-American Internment at Manzanar, accessed October 10, 2015.

[6] Ansel Adams. Roy Takeno, editor, and group reading paper in front of office, ManzanarbRelocation Center, California. 1943. Ansel Adams’s Photographs of Japanese-American Internment at Manzanar, accessed October 10, 2015.

[7] Ansel Adams. Mess line.

[8] Barre Toelken. “Cultural Maintenance and Ethnic Intensification in Two Japanese American World War II Internment Camps.” Oriens Extremus 33, no. 2 (July 1985): 80, accessed November 4, 2015.

[9] Toelken, “Cultural Maintenance,” 79.

[10] Toelken, “Cultural Maintenance,” 79.

[11] Toelken, “Cultural Maintenance,” 79.

[12] Toelken, “Cultural Maintenance,” 79.

[13] Toelken, “Cultural Maintenance,” 76.

[14] Toelken, “Cultural Maintenance,” 76.

[15] Thomas A. Guglielmo and Earl Lewis, “Changing Racial Meanings: Race and Ethnicity in the United States, 1930-1964,” in Race and Ethnicity in America: A Concise History, ed. Ronald H. Bayor, New York: Columbia University Press, 2003, 181.

[16] Tonai, “A Short History,” 35.

[17] Tonai, “A Short History,” 35-36.

[18] Tonai, “A Short History,” 35-36.

[19] Tonai, “A Short History,” 35.

[20] Tonai, “A Short History,” 37.

[21] Casey J. Pallister “George “Montana” Oiye: The Journey of A Japanese American fromthe Big Sky to the Battlefields of Europe.” Montana: The Magazine Of Western History 57, no. 3 (September 2007): 22 accessed November 5, 2015.

[22] Pallister, “George,” 28.

[23] Pallister, “George,” 29-31.

[24] Pallister, “George,” 29.

[25] Rocío G. Davis. “National and Ethnic Affiliation in Internment Autobiographies of Childhood by Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and George Takei.” Amerikastudien 51, no. 3 (September 2006): 360, 363, accessed November 3, 2015.

[26] Lane Ryo Hirabayashi. “Wakako Yamauchi’s “The Sensei”: Exploring the Ethos of Japanese American Resettlement.” Journal Of American Ethnic History 29, no. 2 (Winter2010 2010): 3, accessed November 3, 2015.

[27] Hirabayashi, “Wakako,” 3-4.

[28] Hirabayashi, “Wakako,” 4-5.