World War II was a war that enveloped all of American society even if it was not fought on American soil. This, of course, affected all American citizens, but it especially had a huge affect on certain ethnic groups within America – in particular Italian Americans. Previous to the war, Italian Americans had strong ties to their homeland, whether it was through an idealization of their home, remittances to family members, or through political involvement. The war not only unified Americans all across the country, but also worked to Americanize outlying ethnic groups like the Italian Americans. Because of World War II, the Italian-American community was forced to reexamine their ethnic identity and political support of Italy.

During the pre-war era Italians faced discrimination as a result of white American nativism, a movement against foreigners. Much of this anti-foreigner attitude influenced the Italian community to distance themselves from American society and caused them to keep strong ties to their homeland. Since the start of Italian immigration, there was an interesting juxtaposition of Americans viewing Italy as a place of knowledge due to the renaissance, meanwhile newspapers and other media sources portrayed them as lazy, tricky, and as criminals.[1] One example of this was the New Orleans newspaper, The Mascot which described them as “ditzy, lazy, ignorant, and prone to violence”.[2] Tensions caused by dangerous stereotypes of Italians often broke out in violence against them across the country, New Orleans being one of the most famous. In the 1880s and 1890s New Orleans had a very large Italian population with a large anti-Italian populace to go along with it. The most exemplary instance of this was October 19th, 1890 when the police chief Hennessey was shot and Italians were immediately blamed due to his tense relations with them.[3] A hundred Italian men were rounded up; nine of these men were put to trial and found not guilty due to insufficient evidence. The people of New Orleans were not happy about this and on March 14, 1891 a mob stormed the prisons, hanged two of the suspects and shot nine other Italian Americans in the prison.[4] There was no strong backlash against the mob by white Americans; the New York Times even went so far as to publish an article entitled “Chief Hennessy Avenged, Eleven of his Italian Assassins Lynched by Mob” thus publically taking the side of the police chief.[5] Events like the lynching in New Orleans and many other attacks on Italian American citizens caused the Italian American community to feel alienated from the rest of American society.

Due to discrimination, Italian Americans saw themselves as different from the prominent American image which reinforced their ties to back home. Before WWII in the late 19th century and early 20th century Italians coming to America had to try to assimilate into the popular white American society as a part of “making it in America.”[6] The divide between racial and ethnic discrimination is very important to understand when looking at Italian Americans. Italians were viewed by most white Americans and the government as “white” in a racial sense but ethnically they were still viewed as Italian and therefore inferior.[7] Because of this, Italians were able to take advantage of the advantages of being white, such as access to housing, jobs, and public areas, though they still received more social discrimination. As a result of their ostracization they did not see themselves as white, even though the rest of society did, instead identifying with the “Italian race”. This idea is important to understand how they were treated and the draw to Mussolini’s campaign of “making the Italian race great again.”[8]

Istituto Luce, Fascist Italy Newsreel, published 1943, found on archive.org and listed in the National Archives.

The Italian American community looked homeward as Benito Mussolini rose to power in Italy during the 1920s and 1930s. His campaigns restarted Italian national pride in Italians residing in America. This came at a time when the American government enacted the 1924 Immigration Act which would severely stem the flow of Southern European immigrants, something that many Italian Americans saw as an attack.[9] Mussolini gained popularity within the Italian public as he campaigned for resurgence in Italian greatness. He was an incredibly powerful public speaker as well as a charismatic leader that garnered support from a lot of Italian citizens at first, as well as people abroad.[10] After Mussolini became leader in a coup replacing the old government he urged for a “triumph of law and order over anarchy and anarchism” in a highly-fractioned country still pulling its identity together after a recent governmental unification.[11] Mussolini most notably violently suppressed the mafia (a very large criminal institution within the country), socialists, anarchists, and any other radical groups. His methods were often violent and corrupt, thus leaving many Italian citizens under attack. Despite his tyranny, unbeknownst to most of the Italian American community, support for Mussolini reached its peak after two main events: the success of the Ethiopian War and the sanction of Mussolini’s rule by the pope[12] Due to this and other militaristic enforcement there was an anti-fascist movement within Italy and with the Italians that fled Italy to America, only to be confronted with a huge pro-fascist movement within the Italian American community there.

Photo taken by Marjory Collins, 1943 Feb., “New York, New York. Girolamo Valente, Italian-American newspaper editor correcting proof of La Parola, his progressive weekly newspaper.” From Library of Congress: Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information Photograph Collection.

The Italian-Americans were generally split into two political points of view in America leading up to WWII: the pro-Mussolini fascist Black Shirts, the name of Mussolini supporters, and the Italian anti-fascists. In America, pro-fascists were very pervasive and generally involved in pro-Mussolini campaigns as well as a rise in Itali

an nationalism. This took the form of Italian language newspapers, Italian taught schools, the Catholic Church, Italian American worker unions and fraternal organizations, and more.[13] They would also send back remittances to their relatives in Italy in support of the country and the unification of Italy.[14] On the other side though there was a minority of anti-fascists found in Italian-American communities that did not support what Mussolini was doing in Italy. Their political agenda was spread through anti-fascist newspapers like Il Progresso, La Parola, and Il Martello, the latter edited by known anti-fascist and anarchist Carlo Tresca. In addition to this, they had a letter-writing campaign protesting the fascist government, celebrated holidays like Primo Maggio, held rallies, and aided those persecuted back in Italy under Mussolini.[15] While the anti-fascist community was very small before the war, this divide in the Italian American community would become important in how their ethnic identity would change over the course of the war.

The start of the war and having Italy as an enemy brought on a new wave of distrust for Italian Americans in the eyes of white Americans. This increased the need for Italian Americans to assimilate into American society and be accepted by white America. Americans saw this rise of support for Mussolini as anti-American. After an investigation in the late 1930s by the House Un-American Activities Committee looking into the fascist movement happening on American soil, 600,000 non-documented Italians were seen as enemy aliens, 4,000 were taken into custody, and about 200, were interned like the Japanese Americans.[16] The ones seen as enemy aliens were under close observation by authorities, had to follow a curfew, and even had personal possessions taken from them.[17] Because of this, the Italian American fascist groups in America took a hit and eventually started break off out of fear of punishment from the government.[18] This fear of Italian Americans was not completely unfounded as up until the attack on Pearl Harbor, Italian American newspapers were still loyal to Italy.[19] This added to the question of whether or not Italian Americans could be trusted during the war. So if anything the war rekindled some of the fears of Italians from white Americans.

In response to distrust of Italian Americans from white Americans, they used the war as a way to politically ally themselves with America and cut off ties to their homeland. Tides were turned on the fascist movement as fascism quickly became anti-American, and anti-fascism gained popularity. Anti-fascist newspapers like Il Progresso and leaders like Carlo Tresca were put at the front of the resurging anti-fascist movement.[20] During the war, the movement aligned itself with America in its destruction of Mussolini and fascist dictatorships over in Europe. In Carlo Tresca’s words, “we hate Nazism, Fascism, totalitarianism… We hope, in the depths of our conscience, that victory smiles on the enemies of Italy, Germany, and Japan…today we say: on American bayonets rest, for all of us whose backs are against the wall in this difficult hour…”[21] After the war many fascist group leaders were arrested and held for trial for not supporting America during the war. Help with rounding up the fascists came from unexpected allies like Carlo Tresca who would often work with the FBI and supply of lists of people involved in fascism.[22] Anti-fascists and the Italian American community on a whole turned from their home nation and sought allegiance with their new home.

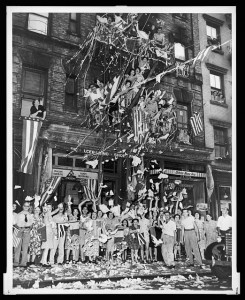

Photo taken August 14, 1945, “Residents of New York’s “Little Italy” in front of 76 Mulberry St., greet the news of the Jap[anese] acceptance of Allied surrender terms with waving flags and a rain of paper.” From Library of Congress: New York World – Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection.

As the war came to a close and Mussolini was defeated, Italian Americans started to see themselves in a new light. As a result of the war and due to their efforts, Italian Americans saw themselves as more of white Americans for their participation for the American side.[28] The war changed a lot within the community but ultimately did not do much for outside views of them. This whiteness that they embraced as a result of the war is sometimes described as a “conditional whiteness” because some Italian Americans feel that it is the assimilation with the American culture and loss of their old customs that has made them less Italian and more American.[29] Negative stereotypes popular before the war were still present in popular media and culture, especially in regards to mafia associations. These topics would become prominent questions that the Italian American community faced as they tried to figure out their ethnic identity and what it means to be American in the coming years.

References

[1] Jerre Mangione and Ben Morreale, La Storia: Five Centuries of the Italian American Experience (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1992), 201.

[2] Mangione and Morreale, La Storia, 203.

[3] Mangione and Morreale, La Storia, 205-206.

[4] Dorothy Hoobler and Thomas Hoobler, The Italian American Family Album (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 60.

[5] Mangione and Morreale, La Storia, 211.

[6] Fred L. Gardaphé, Leaving Little Italy: Essaying Italian American Culture (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2004), 125.

[7] Thomas A. Guglielmo, White on Arrival: Italians, Race, Color, and Power in Chicago, 1890-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 6.

[8] Guglielmo, White on Arrival, 113.

[9] Mangione and Morreale, La Storia, 316.

[10] John P. Diggins, Mussolini and Fascism: The View from America, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1972), 59.

[11] Diggins, Mussolini and Fascism, 30.

[12] Nunzio Pernicone, Carlo Tresca Portrait of a Rebel (New York: Palgrave MacMillian, 2005), 196.

[13] Guglielmo, White on Arrival, 114.

[14] Mangione and Morreale, La Storia, 319.

[15] Kathleen Neils Conzen, David A Gerber, Ewa Morawska, George E Pozzette, and Rudolph J Vecoli, “The Intervention of Ethnicity: A Perspective from the USA,” in American Immigration and Ethnicity, ed. David Gerber and Alan Kraut (New York: Palgrave Macmillian, 2005), 94.

[16] Pernicone, Carlo Tresca, 254.

[17] Diggins, Mussolini and Fascism, 400.

[18] Pernicone, Carlo Tresca, 252.

[19] Diggins, Mussolini and Fascism, 399.

[20] Diggins, Mussolini and Fascism, 402.

[21] Pernicone, Carlo Tresca, 252.

[22] Pernicone, Carlo Tresca, 254.

[23] Hoobler and Hoobler, The Italian American Family Album, 93.

[24] Thomas A. Guglielmo and Earl Lewis, “Changing Racial Meanings,” in Race and Ethnicity in America, ed. Ronald Bayor (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 179.

[25] Mangione and Morreale, La Storia, 340.

[26] Hoobler and Hoobler, The Italian American Family Album, 93.

[27] Hoobler and Hoobler, The Italian American Family Album, 93.

[28] Guglielmo, White on Arrival, 6.

[29] Gardaphé, Leaving Little Italy, 125.