Southern Trip Discoveries: An Addendum to a Past Post- Moravians Were Copyists Far and Wide

By Olivia Armandroff, WPAMC Class of 2020

In a previous post, I explored a collection of drawings from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries done by students at Nazareth Hall, a Moravian Boarding School in Pennsylvania, which are now collated in a scrapbook in the Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Ephemera at Winterthur. The students’ work shows they were adept at copying from prints, such as The Death of General Schwerin, which one student attributed to an original painting by George Beckel, and copies of architectural renderings from Pain’s British Palladio. These copies show how a small, rural early-American community was invested in a larger and longer art historical tradition.

Figure 1. Christian Daniel Welfare, after Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, c. 1825. Oil on canvas. 56 x 47 inches. Wachovia Historical Society Collection. Image courtesy of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.

On Winterthur’s trip to the South, I had the opportunity to visit a different Moravian settlement—Salem, North Carolina—and explore the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts’ collection of Moravian art and material goods—including paintings by Christian Daniel Welfare (1796–1841). Welfare’s early years in Salem were spent teaching at the Boys School, where he excelled at drawing instruction. Students were working with red chalk and likely watercolor, and Welfare would have facilitated the production of a body of work that was likely very similar to that going on simultaneously in Nazareth.

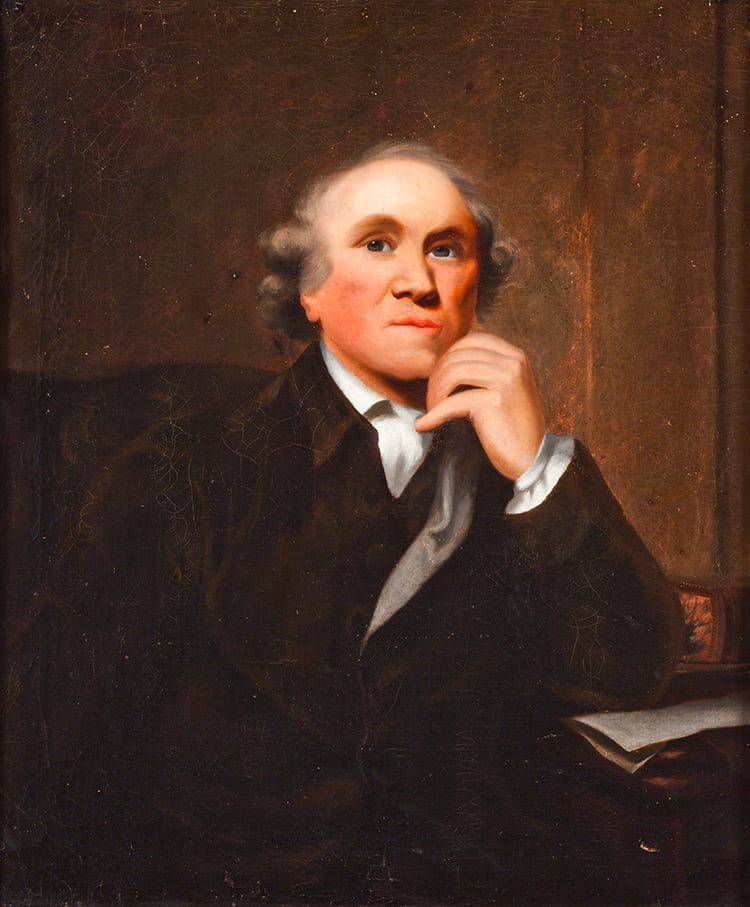

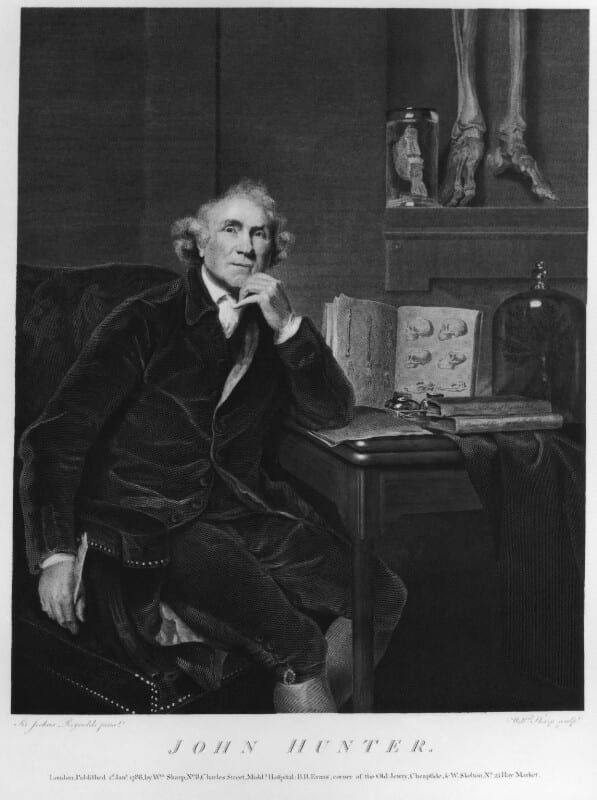

Figure 2. Christian Daniel Welfare, after Sir Joshua Reynolds, John Hunter. Image courtesy of Johanna Brown, Curator of Moravian Decorative Arts & Director of Collections, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.

While Welfare gave up his work at the Boys School, he did not abandon copying. At only twenty, he was known in his community as an artist, and he received a commission from the local botanist Ludwig Von Schweinitz to copy a book containing images of fungi. Eight years later, Welfare traveled to Pennsylvania to receive a formal education in painting with Thomas Sully, and part of that education, as was the norm in both American and European academies, included recreating the works of celebrated masters. In Philadelphia, Welfare copied Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps which was exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts between 1822 and 1829 (Figure 1). In addition, he copied Sir Joshua Reynolds’s portrait of John Hunter, taking artistic liberties, including endowing Hunter with a sterner countenance and simplifying the backdrop (Figures 2 and 3). Copying was not only an educational tool or a means for Welfare to establish his career, indeed, he continued to copy artwork throughout his life, and on a later 1832 visit to Europe for the Moravian Synod, he copied Pompeo Batoni’s The Reclining Magdalene.

Figure 3. William Sharp, after Joshua Reynolds, John Hunter, 1788. Line engraving. 20 1/8 x 15 1/8 inches. Image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

After his education was complete, Welfare returned to North Carolina not only with his copies but with a wealth of cosmopolitan experience, including a familiarity with exhibition spaces such as that of Charles Willson Peale’s museum in Philadelphia. It was likely this precedent that inspired Welfare to set up his own picture gallery in Salem in 1828, which featured changing exhibits of his own and other artist’s work, including the copies Welfare had completed in Philadelphia. As I discussed in my blog post about Nazareth, copies of famous artwork would have functioned as tools of instruction; but in Salem, their placement in a public display suggests copies were a source of entertainment for the community as well. For Welfare, they were a demonstration of his worldly knowledge.

Figure 4. Unknown Chinese Artist(s), after Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper. 94 x 58 inches. Image courtesy of Johanna Brown, Curator of Moravian Decorative Arts & Director of Collections, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.

While the copies in the Nazareth scrapbook are diverse in subject—from pastoral landscapes, to battle views, to anatomical renderings—no piece recreates a religious scene. In contrast, it seems Welfare sought out a religious copy for his gallery. On a subsequent trip to Philadelphia in 1835, he acquired a monumental Chinese copy from Thomas Sully of Leonardo da Vinci’s famous The Last Supper, measuring seven feet and ten inches wide by four feet and ten inches tall (Figure 4). Although Welfare may have been able to copy the precedent himself, he instead chose to invest in the work of other copyists, and by doing so, he involved himself in an international community of artists doing similar work as his own.

Once hung in the gallery, the copy of The Last Supper would have joined other religious works. Welfare had painting images of Christ early in his career, before departing for Philadelphia, and he continued to work on religious subjects after his return. He was also a collector of Christian works by the Bethlehem Moravian artist, John Valentine Haidth. It is interesting to wonder about how Welfare’s Moravian peers in Salem, the visitors to his gallery, would have reacted to Leonardo’s iconic Catholic image in contrast to other religious works by Moravian artists. Would the copy of Leonardo functioned as a devotional object in the gallery space? Or would it have served a similar role as the other copies exhibited in the gallery and been valued as an emblem of artistic virtuosity and painterly beauty?

Leave a Reply