“Preservation Through Production”: Lessons from Hatch Show Print and Dickinson Saltworks

By Elizabeth Palms, WPAMC Class of 2020

This past year, my classmates and I have encountered examples of people preserving historic craftsmanship by using the traditional techniques to make objects in the 21st century. To name a few, we witnessed traditional ceramics production at Gladstone Pottery in Stoke-on-Trent on our British Design History Trip, and we had the treat of working with craftspeople in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Trades during last semester’s Preindustrial Craftsmanship course. During our most recent Southern Field Study Trip, we visited more places where historic craft is alive and well. For now, I am going to discuss two in particular: Hatch Show Print in Nashville, Tennessee and the J.Q. Dickinson Salt Works in Charleston, West Virginia.

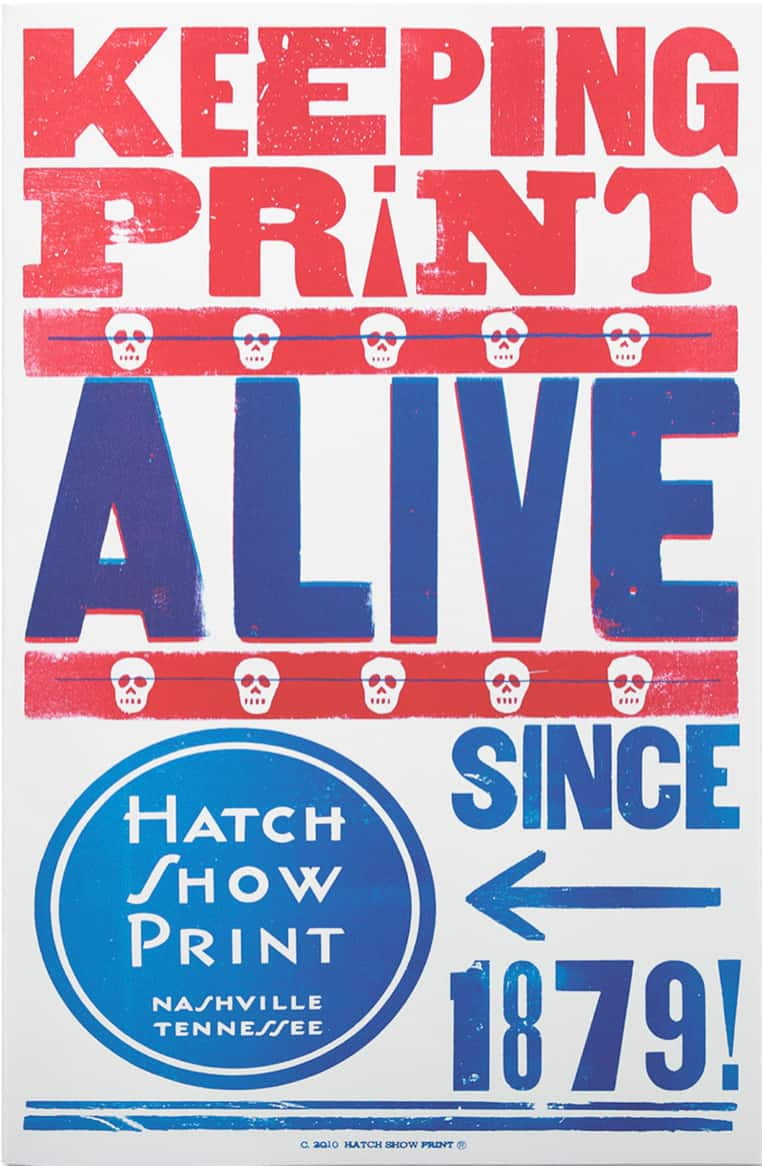

Poster from Hatch Show Print’s Online Collection. I think this particular poster nicely captures Hatch’s Preservation Through Production mission. Courtesy of Hatch Show Print.

In Nashville, our class visited Hatch Show Print, presently housed in the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum building. While it has a rich history, Hatch Show Print is not a museum, but rather an active artistic institution using the same letterpress techniques that its founders, Charles and Herbert Hatch, used when they founded the shop in 1879. Our wonderful hosts, Lauryn Blakkolb and Vicki Chittams, accordingly emphasized Hatch Show Print’s mission: Preservation Through Production. Hatch is preserving the true craft that is letterpress printing in its daily operations, using a variety of 20th-century printing presses, inked by hand, to produce posters that its workers design and set by hand. By appealing to printing connoisseurship, the Hatch website warrants the shop’s invaluable preservation effort: “Today, in this digital era, many consider the results of letterpress printing unrivaled for its subtleties of texture and color; Hatch Show Print carries on this centuries-old process with a 21st-century design sensibility.”[1] Hatch’s team of printer-designers pull from the thousands of pieces of wood type, many of which have been in use at Hatch for over a hundred years, to make their designs. With the equipment and historic wood blocks on hand, they often print restrikes of some of Hatch’s most famous posters, notably for country, folk, and rock and roll music greats such as Johnny Cash, Elvis, Dolly Parton, and more. Some of my classmates and I purchased some of these to take home. The restrike process provides an avenue for Hatch’s printer-designers to practice—and thus preserve—the block printing art form, but they also do so when they design new posters for today’s musical artists and other businesses. New commissions allow them to practice their craft, and execute their individual artistic visions within Hatch’s historical and unique stylistic framework. Hatch’s website describes these prints as “new work inspired by the celebrated blocks.”[2] These new posters, especially those from local Nashville musicians, preserve the Hatch’s original business ethos.

Furthermore, the “Preservation through Production” motto rings true at Hatch on an even deeper level. Not only are the printer-designers keeping the art form of letterpress printing alive in their daily operations, but they are preserving the very woodblocks that have and continue to make it possible by using them. Indeed, the fact that they are using century-old woodblocks is special on a sentimental level—especially for material culture geeks like ourselves.We have learned at Winterthur that utilitarian objects fare best in museum or private collections when they continue to be used. In this sense, Hatch is doing its massive type collection a great service by continuing to keep it in service.

On our drive back to Delaware, we stopped at the J. Q. Dickinson Saltworks in Charleston, West Virginia, where we further saw a “preservation through production” ethos at work. Now, when you think of material culture studies at Winterthur, salt probably does not come to mind! However, Assistant Events Coordinator, Ashton Pence, introduced us to the rich history of salt production in Kanawha County, West Virginia that stretches all the way back to the early 1800s. We learned about the ancient Iapetus Ocean that lies trapped beneath the Appalachian Mountains, making it a perfect and unique spot to harvest salt. William Dickinson, who drilled the first salt well on the property in 1817, founded the saltworks, and Dickinson salt went on to win worldwide acclaim for its high quality. Decades after the saltworks closed, Nancy Bruns and Lewis Payne, brother and sister and 6th-generation decedents of William Dickinson, reopened the saltworks. According to the company’s website, they “have reinvented [the saltworks’s] storied tradition, transforming the process by using natural and environmentally friendly concepts to produce small-batch finishing salt.”[1]

![Two hands cupped together facing upward and protruding into the image from the upper margin (hands pointing downwards in the image). These cupped hands are holding a pile of coarse-grained white salt. Beneath these hands are three planks of some sort of unfinished wood. Above this picture reads, “J.Q. Dickinson [underlined]/ SALT- WORKS.”](https://sites.udel.edu/materialmatters/files/2019/10/J.D.-Dickinson-Saltworks.jpg)

An image taken from the J.Q. Dickinson Salt-Works website. Screenshot from http://www.jqdsalt.com/our-salt/

A bed of salt brine in the final evaporating stage. The water’s salinity at this point is high enough for the salt crystals to form. (Cameo: Tom Guiler). Photo by the author, June 14, 2019.

So to the letterpress printers and natural salt makers of the world, thank you. Not only are you creating incredibly meaningful products, but you are also preserving centuries-old trades—and the histories that go with them—with every print and batch you produce.

[1] http://www.jqdsalt.com/our-story/

[1] http://www.jqdsalt.com/timeline/

[1] https://hatchshowprint.com/what-is-letterpress/

[2] https://hatchshowprint.com/haley-gallery/

Leave a Reply