Put a Cork in It: Classical Ruins and Ecological Time at the Soane Museum

Taylor Rossini, WPAMC ’24

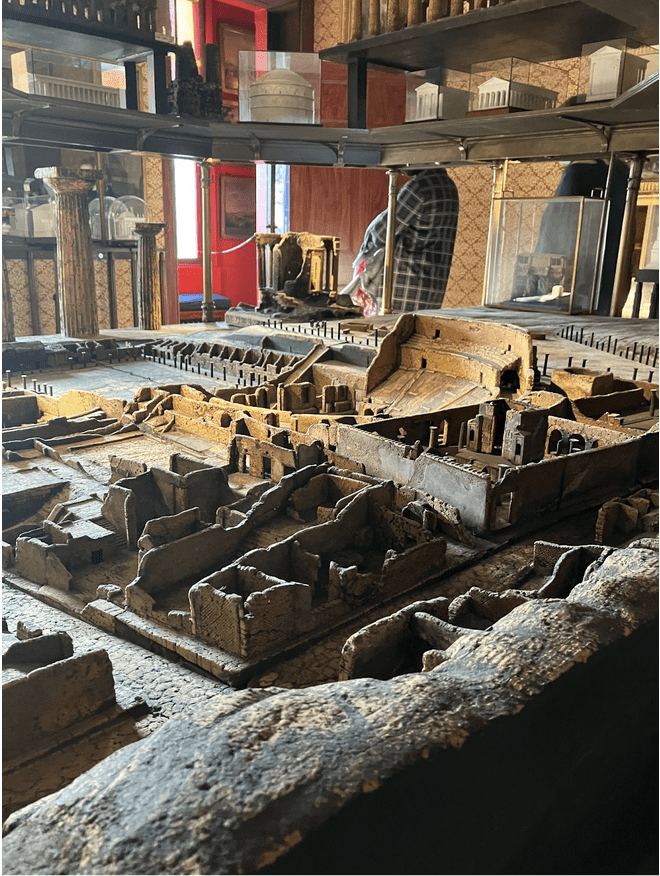

An entire classical city resides inside London’s John Soane Museum. One of the final additions to Soane’s collection, the breathtaking Model Room contains a display of architectural facsimiles depicting some of the most famous monuments of the ancient world alongside some of Soane’s own designs. Most impressive of all is a sprawling topographical model of the Roman city of Pompeii, only recently rediscovered in 1748 and the object of great fascination to an acquisitive and classically inclined Regency public. As it exists in the Model Room, however, Pompeii is not a sparkling classical city on the eve of catastrophe, but rather a weathered and only partially excavated landscape of hauntingly eroded cork.

By the mid-eighteenth century, the extended visit to Italy known as the Grand Tour had become a rite of passage for the British gentry. The purpose of such journeys was to acquire literacy in the classical world, an integral form of social currency in polite eighteenth-century circles, and the spoils of the Grand Tour, both material and intellectual, permeated the homes and collections of British tourists. Safely returned to the refined landscape of English sensibility, collectors could reflect on the aesthetic and moral lessons of a great civilization fallen into ruin.

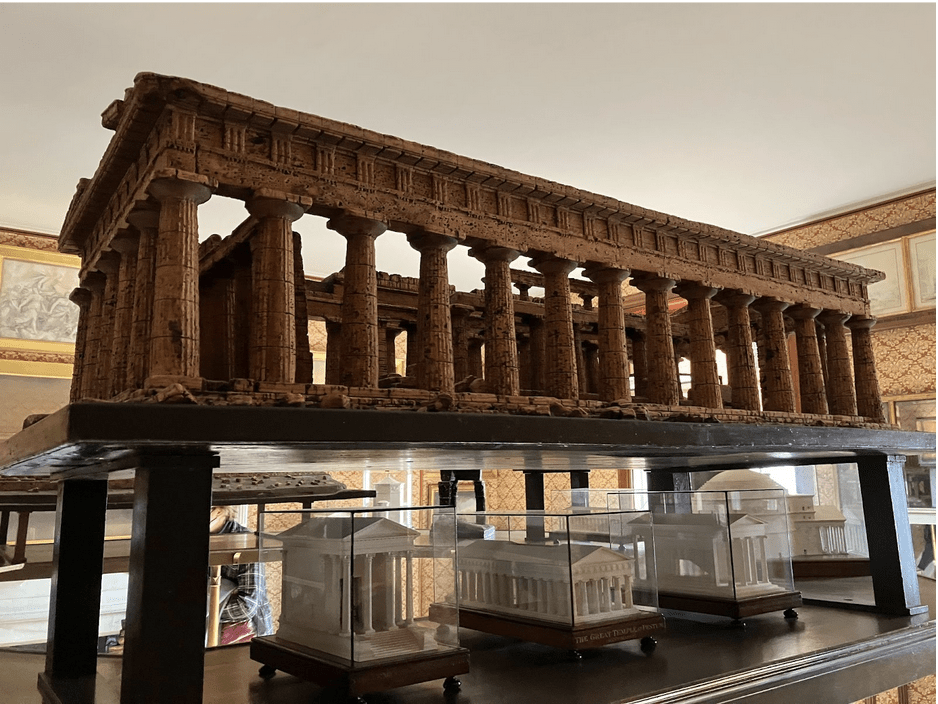

While the plaster architectural models that had become de rigueur purchases for English travelers provided a stark, unblemished, and indeed, as we know today, whitewashed, picture of antiquity, cork models offered a vision of the classical world that was in an evocative state of decay. The porous surface of cork emulated the materiality of classical structures that had weathered millennia of wear. Furthermore, the softness of cork lent itself to being easily worked in minute detail. Cork was thus especially well-suited for souvenir models, which carried the intellectual pedigree of a plaster architectural model, but were lightweight and flexible enough to travel safely home across the mountainous Continent.1

Soane, as a twenty-three-year-old architectural student, had embarked upon his own Grand Tour. His visits to Classical ruins across Italy would provide inspiration for his designs throughout his career, and later in life he amassed a teaching collection of architectural models for his students at the Royal Academy. Soane purchased the large scale model of Pompeii on view today in 1826. Famously buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 72 CE, Pompeii was a source of great fascination to British architects seeking to revive the architecture of the Classical world. Produced by model-maker Domenico Padiglione, the enormous cork model depicts the southernmost segment of the Roman city as it was while still being excavated in the nineteenth century.

Cork models offer a compelling convergence of human and ecological timescales. The cork oak, Quercus suber, is a slow-growing evergreen oak native to the western Mediterranean Basin. A quarter of a century of growth is required before the first harvest can occur, performed seasonally by highly skilled agricultural workers who ensure that the tree is not wounded during the stripping process.2 The trees, which can live over two centuries, are subsequently harvested every nine to twelve years, providing a sustainable biogenic resource. Thus, embedded within a model like Padiglione’s Pompeii are decades if not cumulative centuries of ecological time, harnessed to represent the affective decay of millennia.

Anyone visiting the Model Room today finds themselves, like Soane and his students, towering, godlike, over the antique world. The scale and portability of objects like Padiglione’s Pompeii allowed the grandeur and learning of classical antiquity to be transplanted into eighteenth-century Britain, a powerful ideological claim reinforced by the viewer’s physical dominance over the miniaturized structures. Though perhaps not as well-studied as contemporaneous plaster architectural models, the Soane Museum cork model collection reminds us of the central role such objects played in the British project of “bearing Rome across the Alps.”

1 Richard Gillespie, “The Rise and Fall of Cork Model Collections in Britain,” Architectural History 60 (2017): 118.

2 Oliver Wilton and Matthew Barnett Howland, “Cork: An Historical Overview of Its Use in Building Construction,” Construction History 35, no. 1 (2020): 2.

[…] https://sites.udel.edu/materialmatters/2023/11/20/put-a-cork-in-it-classical-ruins-and-ecological-ti… […]