“An Entirely New Note in Art”: Room Portraits in the Early-Twentieth Century

By Olivia Armandroff, WPAMC Class of 2020

We commonly think of portraiture as a genre dedicated to human sitters, but the phenomenon of house portraiture has been alive since the mid-sixteenth century. While depictions of the facades and grounds of stately country homes are common in the tradition of British painting, interior room portraits only came to flourish in the late-nineteenth century, when periodicals dedicated to interior design proliferated. Photography offered a new means of documenting interior spaces in the second half of the nineteenth century and voyeuristic articles and publications such as Artistic Houses, printed between 1883 and 1884, offered readers the opportunity to see behind the curtains, into the homes of the wealthiest American citizens. The home’s interior was understood as a place that reflected the character of its owner, and in many ways, a room portrait served an equivalent role to a human one, visualizing a person’s identity.

Fig. 1. William Bruce Ellis Ranken, The Gasperini Room, Royal Palace, Madrid, Spain, 1926. Oil on board, 45 5/8 x 34 5/8 in. Reading Museum and Town Hall.

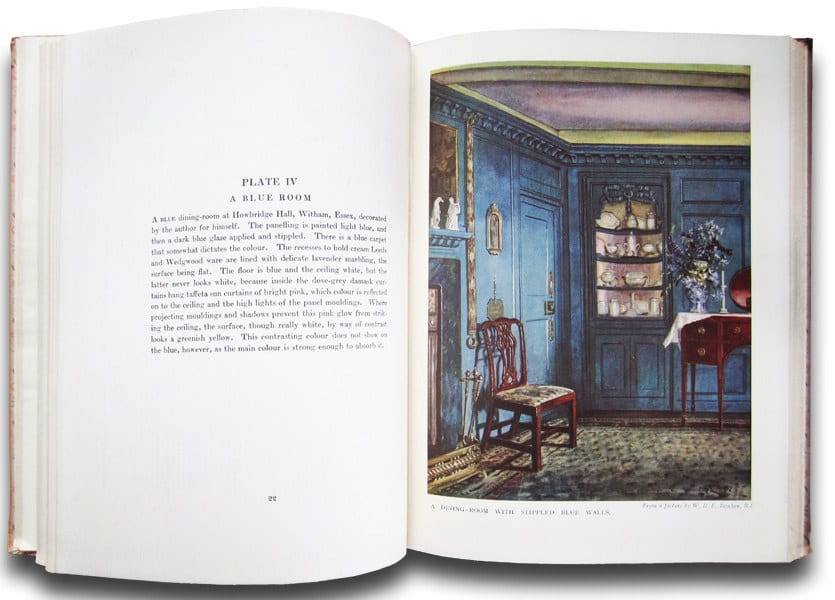

Although the technology existed to capture rooms with photography, and the majority of articles in periodicals such as Country Life and Arts & Decoration were illustrated with photographs, many periodicals opted to commission artists such as William Bruce Ellis Ranken to produce impressionistic renderings of interiors as illustrations for special features. The Scottish-born Ranken had grown up in a life of privilege, and after an education in art both at Eton and at the Slade School, he began to practice in Chelsea and in the milieu of John Singer Sargent. Ranken excelled technically in the qualities Sargent’s work is most often praised for: luminescent colors, rich texture, and an evocative rendering of drapery. But while he ventured into portraiture, he was most prolific in his production of room interiors, something he began in 1916 with the first renderings ever made of the interiors of Blenheim Palace. He continued in the tradition of British country house portraiture, courting Europe’s most elite patrons including in his series of Spanish royal palaces and in the completion of many commissions from the British Royal Family (Fig. 1). But he also had success in maintaining a transatlantic career, and with introductions from Sargent and the photographer Baron de Meyer, he rendered the homes of the Vanderbilts, Whitneys, Astors, and Havermeyers. He circle included independently-wealthy, American interior designers, and he maintained friendships and depicted the homes of Elsie de Wolfe and Henry Davis Sleeper. Partnering with the well-regarded British interior designer Basil Ionides in the 1920s, Ranken completed a series of illustrations for Ionides’s book, Color and Interior Decoration, released by Country Life in 1926 (Fig. 2). In a period before color photography, Ranken’s painted illustrations were essential contributions in effectively representing the rooms’ tonalities.

Fig. 2. William Bruce Ellis Ranken, “A Blue Room,” in Color and Interior Decoration (London: Country Life, 1926).

Fig. 3. Walter Gay, Interior of the Bedroom of the Chateau du Breau, ca. 1912. Oil on canvas, 21 3/8 x 25 13/16 in. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

These room interior portraits, especially those produced for publication, stand at a fulcrum between designs for stage settings and commercial displays, illustration, advertisement, and fine art. While Ranken’s work is perhaps best known today through reproductive illustrations, it ought to also be appreciated as art. It bears an uncanny resemblance to the work of his contemporary, Walter Gay. Although American, Gay’s biography has striking resemblances to Ranken’s. Born into a wealthy Boston family, Gay like Ranken crossed the Atlantic, this time in the opposite direction and many years earlier. In the 1870s, under Leon Bonnat’s gaze, and alongside John Singer Sargent, Gay received his artistic education in Paris where he developed an appreciation for light and color. Remaining in France, he became best known for his genre paintings of local peasants that followed. Like Ranken, Gay’s independent means allowed him to freely select his subjects, without regard for patrons’ taste, and he would abandon the figure by 1895 when he began to paint opulent interior settings of French homes (Fig. 3). In 1913, for Art and Progress, A. E. Gallatin wrote about Gay’s interiors, calling his “portraits of rooms . . . a record of their owner’s personality” and “an entirely new note in art.” Gallatin drew a connection between Gay’s meticulous rendition of interior décor with both the Dutch interiors painted by Vermeer and Georgian rooms Hogarth captured but, given that both these forbearers incorporated figures into their compositions, Gallatin concluded that “seldom . . . has an artist painted a room entirely for its own sake.”

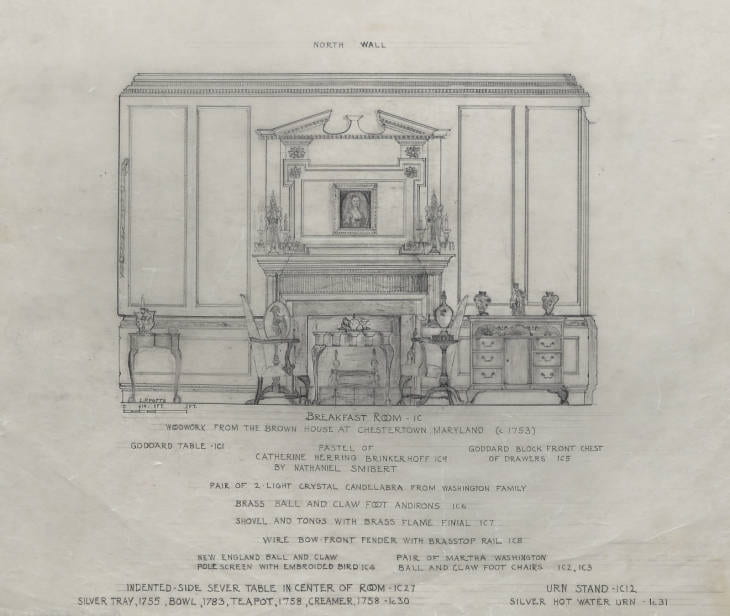

Henry Francis du Pont hung one of Walter Gay’s portraits of French interiors in the Cottage, his home after the main house at Winterthur opened as a museum. Even before this time, du Pont was invested in room portraiture. When building projects ceased during World War II, du Pont requested that Leslie Potts, who was already working at Winterthur in farming operations, occupy himself by rendering several rooms in the house. Potts had been trained as an architect, and he relied primarily on the genre of the birds-eye view, but he also completed elevation drawings of rooms which have much in common with interior room portraits (Fig. 4). In addition to taking into account the architecture of the spaces, his drawings meticulously represent the placement of objects and are a means of understanding the arrangement of the home in a time when du Pont was living in it.

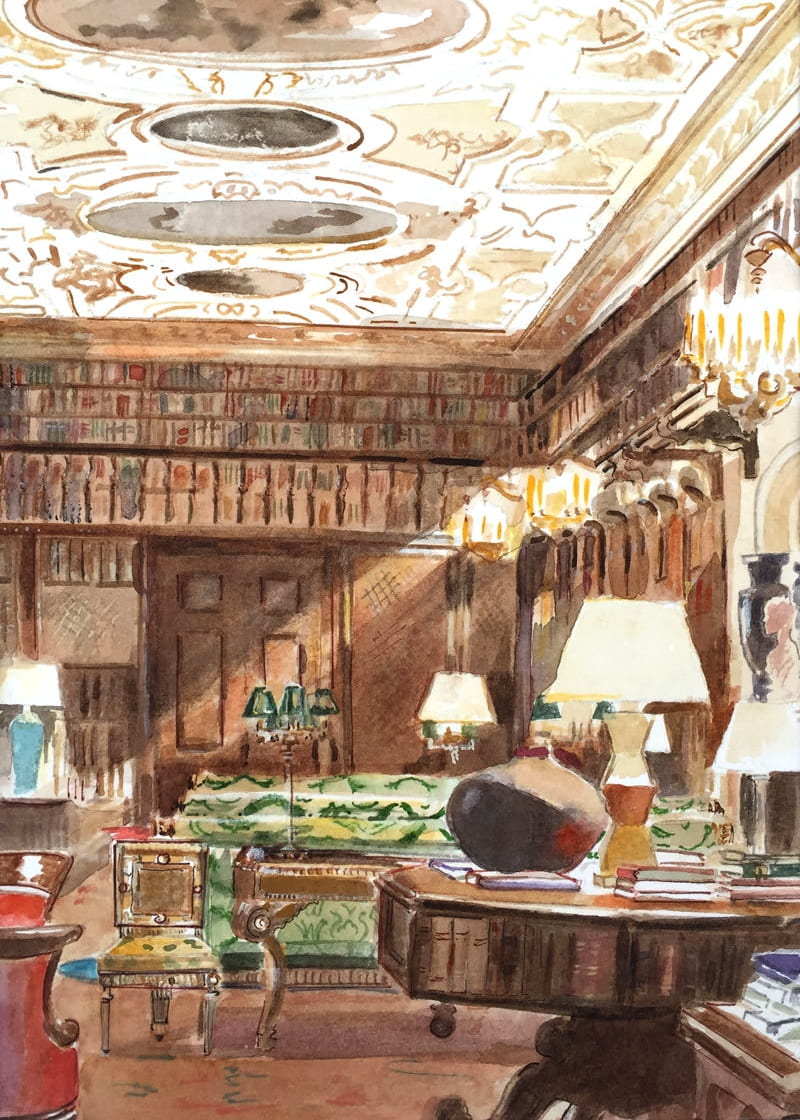

Gay’s unique subject choice did not stir legions of imitators in the world of fine art. Instead, when his French room portraits were exhibited in New York in 1920, they might have been recognized as the final, lingering traces of a Gilded Age aesthetic to be displayed in the face of rising modernism. But the art of capturing room portraits did not die out. In fact, magazines such as Architectural Digest remain patrons of such artwork today. In 2017, the magazine recognized the loss of Jeremiah Goodman who had captured the homes of both the wealthy and celebrities since beginning his illustration career in 1948. In his stead, it has recognized artists such as Mita Corsini Bland and Isabelle Rey, who continue to work in the lineage established by Ranken and Gay a century ago (Fig. 5). The palimpsest of John Singer Sargent’s Gilded Age style is still alive within the pages of interior design magazines today.

Leave a Reply