What Story Lies Behind Those Gray-Brown Eyes?

By Peter Fedoryk, WPAMC Class of 2021

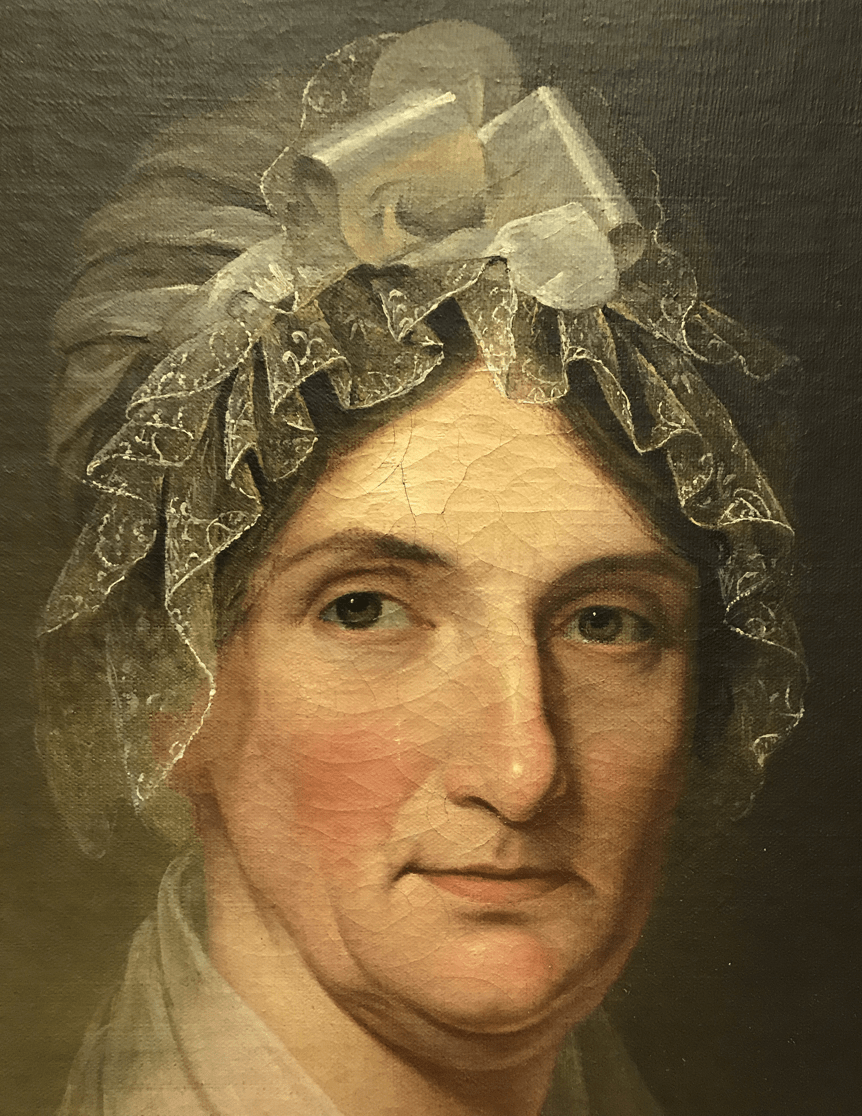

Peale, James. Portrait of Catharine Bicking Reynolds Kuhn, c.1804. Oil on canvas. 30 1/4 x 25 inches. Winterthur Museum, Gift of Stiles Tuttle Colwill, 2018.0001.

Sitting directly in front of Catharine, I know she isn’t looking at me. She’s looking over my shoulder, back when she was being painted, at James. He was probably standing a little behind me and to my left. I can tell from the way her pupils rise a touch higher in her eyes than they need to be to see me. Some portraits stare at you wherever you are, but not Catharine—her attention is fixed on someone else (Fig. 1).

Catharine was born Catharine Bicking, and then was Catharine Reynolds when she married John Reynolds, and after he died she became Catharine Kuhn when she remarried to John Kuhn. I know this because she wrote it down, or someone else wrote it down, and some third party-else decided that what they wrote down was worth keeping. It was when she was Catharine Kuhn that James Peale painted her in a golden-brown short sleeve dress that had a scooped neckline, with lace wrapped round her neck and tucked down the front. Even though someone wrote parts of her life down, oftentimes it’s more with the unwritten information that I feel I can connect.

James was very kind with her face; he painted it exceptionally soft (Fig. 2). He used gentle blends of creams to contour her skin, and added rosiness to her cheekbones where it may or may not have been, and only indicated that she might be an older woman by the highlighted shadows of her jowls and neck lines. There is no smile upon Catharine’s face—at first glance. The more I look, the more I see the gentle upturn that could just be forming at the corners of her mouth. Because I don’t think she looks severe. Austere, yes, maybe—but not severe. She’s sitting in a chair that seems to act the way I imagine she would. The sharp definition at the end of the right arm of the chair, where it looks like a perfect quarter-circle was carved out, seems pointed (Fig. 3). If I were James, I would have painted it so for a reason. Think of all the other ways he could have painted the end of the chair arm. It could be flowing and languid, or full of fretwork and playful, or it could have no arm at all.

I don’t know why Catharine commissioned James to paint this portrait. It’s possible it coincided with her marriage to John Kuhn, in 1804. Catharine is wearing a single golden band on the middle finger of her right hand, after all, but rings can mean all sorts of things (Fig. 4). There’s a signature on the portrait that tells me James painted it (a faint “IP” in muddied brown) and James seems to always include a date below his signature (Fig. 5). It must be there, but my eyes can’t see it. Time has worked against me there, aging the paint and adding layers of who-knows-what that prevent me from seeing the year 1804, or 1810, or 1817, or any other year. One high-resolution photograph later, several keystrokes to enhance the contrast, and a final click to flip the image to negative confirms what my eyes could not (Fig. 6). 1812. John won’t join us in the room for now, then, the portrait couldn’t have been painted for their marriage. But then, for what? And why?

These are the conversations I have while I puzzle in front of paintings. I put myself in each pair of shoes and think about what makes sense and what doesn’t. The better I get to know the person the better I can answer those questions. Right now I don’t know Catharine very well, nor James. But I have to, otherwise I’ll never know what story lies behind their lives, their interaction, and the world that was happening around them while Catharine sat in that chair looking a little up and to her left, towards James and his canvas, as he painted a mesmerizing moment in time that serves as my doorway into their lives.

Leave a Reply