John Shaw’s Annapolis

By Bethany McGlyn, WPAMC Class of 2020

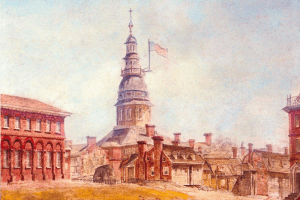

Detail of Charles Cotton Milbourne, View of Annapolis, Maryland, ca. 1794. Watercolor on paper. Image courtesy Hammond-Harwood House.

One of my favorite early views of Annapolis, Maryland is the above image, which was painted in watercolor by Charles Cotton Milbourne in 1794. Milbourne’s picture of Annapolis is dominated by the still-unfinished Maryland State House, which towers above the landscape. Attached to the balcony of the State House and waving proudly in the breeze is an American flag, one that is quite different than the other flag—the one associated with Betsy Ross—that often reminds us of early America.

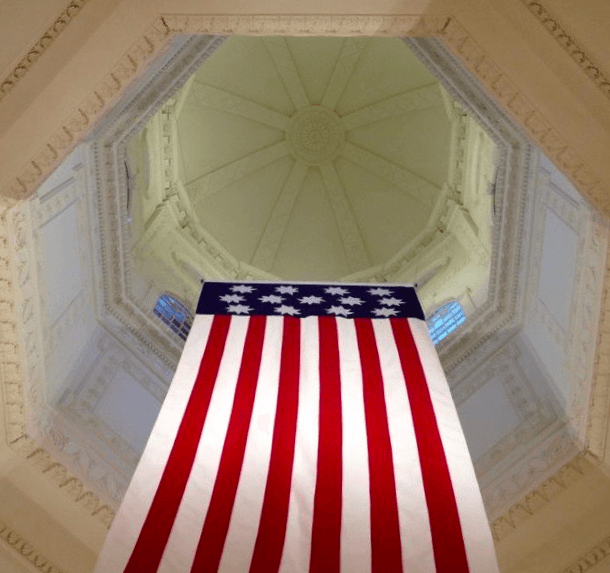

Though the flag that Milbourne painted flying high above the city of Annapolis is different, it contains all of the components necessary for an early American flag: thirteen stripes alternating in white and red, and thirteen white stars on a blue background. The flag depicted by Milbourne never gained the same popularity as the so-called Betsy Ross flag, but modern replicas still line the brick and cobblestone streets of the city, as well as a massive reproduction that sometimes hangs from the dome of the Capitol.

- Reproduction John Shaw flag hanging in the Maryland State House. Photo by Bethany McGlyn.

- Reproduction John Shaw flag hanging outside an Annapolis home. Photo by Bethany McGlyn.

The flag that once flew above Annapolis is a fascinating object—one that is testament to the talent and civic mindedness of its creator, Scottish immigrant and cabinetmaker John Shaw; and one that reminds us of a time when Annapolis was the most important city in the young United States.

John Shaw (1745-1829) left his native Glasgow for Maryland’s capital city sometime in the early 1760s. Little is known of his early life or the initial years of his career, but Shaw has become a figure emblematic of the quality and quantity of fine furnishings made in eighteenth-century Annapolis. Shaw built chairs, sofas, bookcases and more for some of the most prominent Marylanders—including the Carroll, Paca, Chew, Ridout, Ogle, and Chase families, for example.

However, like many artisans in early America, Shaw was skilled in a variety of trades and used his talents and connections for many purposes. He worked as an undertaker, sold imported goods, and made smaller objects like tea caddies and ballot boxes. Despite this impressive resume, I was puzzled when I first learned of Shaw’s American flags. Why commission a cabinetmaker to create a flag? Why choose Shaw in particular?

With the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783, Annapolis became the temporary capital of the United States of America. Maryland Governor William Paca commissioned Shaw to create two flags—one to hang outside of the Governor’s Mansion, and one to hang from the State House—in preparation for the arrival of Congress in Annapolis. The new flags would serve as a visual and material signal that not only represented the arrival of a new national government, but also denoted the importance of Annapolis itself.

Like Governor Paca, John Shaw was an ardent patriot. He was appointed Armorer of the State in 1777 and served during the Revolutionary War in the Severn Battalion, rising to the rank of sergeant-major by 1779. Additionally, Shaw had been commissioned to build furniture for the State House as early as 1775, when he worked in partnership with another Annapolis cabinetmaker, Archibald Chisholm. As Shaw became more and more successful, his involvement with designing, furnishing, and maintaining the interiors of the State House—especially the Old Senate Chamber—deepened. Shaw has often been described as an “unofficial caretaker” of the State House and the Armory, and it seems likely that his commitment to the building, to the city, and to the nation made him the perfect choice to create Annapolis’s new American flag.

The flag painted by Charles Milbourne speaks to the diversity of John Shaw’s talents and responsibilities, the high esteem with which he was regarded by members of his community, and to the importance of the city on the Severn to our understanding of early America.

For further reading:

- “John Shaw and the State House, 1783,” http://marylandstatehouse.blogspot.com/2012/07/john-shaw-and-state-house-1783.html

- “A Corrected Replica of the Flag From Maryland’s 1783 State House Will Be Raised,” http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/06/12/AR2009061203917.html

Leave a Reply