Leather as a By-Product: Moravian Edition

Last December, as I perused the leather conservation and tanning section in Winterthur’s library, I came across a single sentence that completely changed everything I thought I knew about the physical material of leather. In the first line of his 1922 handbook Practical Tanning, Dr. Allen Rogers states, “The hides and skins used in the manufacture of leather are generally obtained from animals killed for food.” Contextualizing leather as a by-product of our food industry, not solely as a by-product of animals, was a concept I had never fully realized despite having a few years of experience as a leather researcher under my floral-tooled belt. It is quite an obvious statement made by Rogers, but it was one that made me consider in new ways how museums of American decorative arts interpret the physical material of leather. It was not until my class took a gallery tour with Johanna Brown, Curator of Moravian Decorative Arts & Director of Collections at Old Salem Museums & Gardens on our 2018 Southern Trip, that I became fully content with a museum’s interpretation of leather objects.

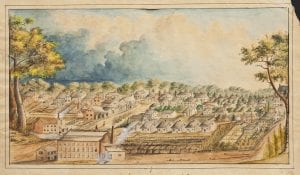

This c. 1852 landscape of Salem is overlooking the village from the West. Depicted in the left foreground is the Salem Cotton Factory and the Fries Woolen Mill. Possibly Mary Steiner Denke (1792-1868), Salem, North Carolina, watercolor on paper, Wachovia Historical Society (P-17), gift of Mr. Fred Bahnson. Photograph courtesy of Old Salem Museums & Gardens.

As my cohort stood near the entrance of the Dianne H. Furr Moravian Decorative Arts Gallery at the Frank L. Horton Museum Center at Old Salem/MESDA, Johanna pointed to an 1852 landscape of the Moravian settlement of Salem, North Carolina. She described the large buildings in the left foreground of the watercolor as depicting the village’s thriving industry. Two of Salem’s most prominent industries—the Salem Cotton Factory and the Fries Woolen Mill—dominate the scene, but Johanna was quick to add that a thriving leather industry also existed.

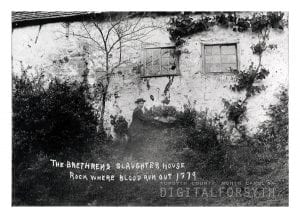

The man in this c. 1895 photograph is standing near the “rock” or drainage spout where blood from slaughtered livestock would dump out of the Single Brethrens’ slaughterhouse. The slaughterhouse, built in 1784, was a major industrial building in Salem. The building was used for the slaughter of cattle until 1803. In 1816, Karsten Peterson converted the building for use as a furniture-making shop. His descendants continued that business until the 1890s. In 1897, part of the building collapsed, and in 1917, it was demolished. Photograph courtesy of the Old Salem Digital Forsyth and Old Salem Museums & Gardens.

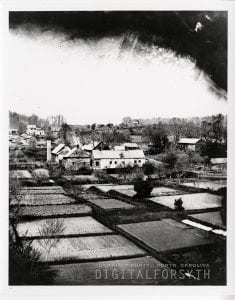

The flourishing leather industry in Salem’s early history was fueled by the Moravians consumption of meat. Like many bustling trade centers in early America, Salem’s leather industry boasted an industrialized urban plan where the slaughterhouse was built next to a flowing water source outside of the town.

In the foreground of this c. 1885 photograph is the Single Brothers’ garden in Salem, looking west from South Main Street. The buildings in the center of the photograph include the slaughterhouse, the tannery, and the brewery. Photograph courtesy of the Old Salem Digital Forsyth and Old Salem Museums & Gardens.

Part of the slaughtering process meant removing the hides and skins from the livestock and then selling the by-product to a tannery constructed not far from the slaughterhouse. Upon the currier finishing the tanning process, the leather would then enter the town after being sold to the likes of saddlers for upholstery and saddles, harnessmakers for equestrian tack, and trunkmakers for luggage.

The leather upholstered armchair in the Dianne H. Furr Moravian Decorative Arts Gallery at the Frank L. Horton Museum Center. The leather is original to the chair and was likely sourced from the leather industry in Salem. Photograph courtesy of the author.

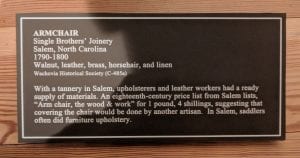

Johanna’s and the gallery’s interpretation of Salem’s leather industry did not end with the watercolor. As we moved further into the gallery I found myself standing in front of an armchair with what appeared to be original leather upholstery, and a label that read, “With a tannery in Salem, upholsterers and leather workers had a ready supply of materials.” I promptly double-checked with Johanna whether she believed the leather was locally sourced, and she gave me a reaffirming yes. This was the interpretation and label I had been waiting for since reading Rogers’ quote in December. The life of this leather likely began as the hide of a bovine whose meat was processed in the Single Brethrens’ slaughterhouse. The hide then travelled through the tannery next door, and the leather was finally distributed to the craftsperson who upholstered the material on the armchair that stood before me. The industrialized urban planning of the Moravian’s eighteenth century leather industry was not unlike that made famous by Chicago’s Union Stock Yard in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The interpretive label for the leather upholstered armchair in the Dianne H. Furr Moravian Decorative Arts Gallery at the Frank L. Horton Museum Center. Photograph taken by the author, courtesy of Old Salem/MESDA.

Furniture connoisseurs are captivated with identifying an object’s primary and secondary wood and determining whether the wood was locally or regionally sourced. This captivation is well placed, as determining those factors can tell a connoisseur a lot about the origin of a piece of furniture. However, what can leather on a chair that has never been reupholstered tell a connoisseur about its origin? What about a leather writing surface on a desk and bookcase? Leather, too, has distinct regional and cultural characteristics. With the advancing research in this field of study, museum visitors are sure to experience more excellent interpretations and labels like those found in the Dianne H. Furr Moravian Decorative Arts Gallery.

Kudos to Johanna and the Dianne H. Furr Moravian Decorative Arts Gallery.

By RJ Lara, WPAMC Class of 2019

Leave a Reply