Life in the Living Room: Exploring the World of a Plant Stand

When our furniture curator, Josh Lane, gave us the choice to research any wooden object in the collection for our semester long project, I had no idea what to pick. With so many options, I headed down to my favorite room, the Phyfe Room, knowing I could find something there. On the back wall, beneath the window, was a two tiered plant stand. I got to wondering: what, after all, is the difference between a plant stand and any other kind of table? When did people start keeping plants indoors anyway? And when did plants become so important to people that they started making specialized furniture?

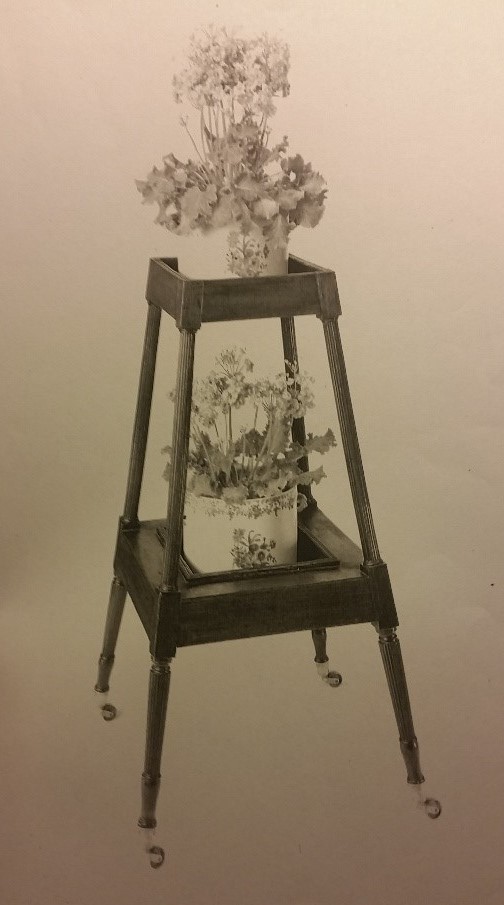

Plant Stand, New York, c. 1820. Mahogany, brass. Winterthur Museum 1957.724

While I knew that cut flowers have long adorned interiors, it was not until I got to digging that I learned that people had been cultivating and loving live indoor plants since the 18th century. However, during the Victorian era, larger sheets of window glass and better regulated household temperature allowed for increasing numbers of plants, and other critters, to survive inside human dwellings. This meant that curiosity cabinets and scientific collections no longer needed to be composed of dead specimens, but could actively grow in the home. And the craze for growing living creatures meant an increased demand for the gear and knowledge to make that possible.

Mrs. William Cooper sits in her parlor among her “pet plants.” The plant stand in the back right resembles Winterthur’s with its splayed legs. George Freeman, Mrs. William Cooper, c. 1816. Watercolor. Fenimore Art Museum, N0145.1977.

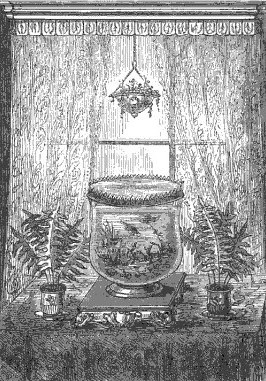

Simultaneous to and in tandem with the living collection craze was an explosion in written and visual materials. Increasing numbers of plant cultivation catalogs were published and articles in Good Housekeeping regularly advised plants as tasteful décor. In addition, houseplants began to make appearances in portraits and indoor genre scenes. While some were illustrated as living on shelves, others lived inside special glasses in the parlor, or in rooms dedicated to creating whimsical indoor gardens.

A Victorian aquarium among ferns and hanging plants. “The Aquarium in the Window,” Cassell’s Household Guide: A Complete Encyclopedia of Domestic and Social Economy (London: Cassell, Petter and Galpin, 1869).

One result of the increased expense and minute knowledge required to maintain a fashionable living collection was that collectors began specializing in specific types of collections. Owners now needed aquariums and manuals for fish cultivation, cases for crustaceans, jars and habitats for insects and cases for ferns. Not only that, they needed the knowledge to keep these critters alive, as well as to maintain their environments beautifully and efficiently. You can only imagine what kind of chaos would ensure from a dirty insect jar, or a spilled crustacean tank! So, rather than keeping a variety of specimans from the natural world on a set of shelves in a cabinet of curiosity, collectors began to keep only very specific collections –crustaceans, or insects, or ferns— in all kinds of new equipment.

Victorian Aquarium and Indoor Garden. From Bernd Brunner, The Ocean At Home: An Illustrated History of the Aquarium (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 2005)

In the case of plants, the most revolutionary equipment was the Wardian case. This special glass enclosure allowed Victorians to grow exotic ferns in a carefully regulated micro-environment. While the glass provided protection from city pollution for the precious pets, copper plates below helped maintain a semi-tropical environment inside. Additionally, owners seemed to have found the shape of the case stylish and beautiful. Inside the glass, they would design miniature faux ruins and archways which echoed contemporary outdoor garden designs, and would place the entire ensemble on complementary plant stands.

Shirley Hibberd, “Arrangement of Wardian Case, c. 1856. In Shirley Hibberd, Rustic Adornments For Homes of Taste (London: Groombridge & Sons, 1858).

Winterthur’s plant stand, specifically, reflects a number of these interests. It raises the plant up off the ground, which provided access to better light, contains a bezel for resting a Wardian glass, and casters so the plant could be moved around the room. Yet, it was constructed from rich mahogany with reeded, splayed legs and detailed decorative moldings. So the plant stand was not only practical–the material suggests it was also important that the stand be fashionable. It was not just about the plant, or the furniture to support it, but the visual harmony of matching the two together and carefully maintaining both. This could be done in an isolated display, or in over-the-top indoor forests. Regardless, if the owner was successful in creating a display, the plants would become the center of attention in the room, demanding questions and compliments from friends. Thus, the plant stand was inherently a specific kind of parlor furniture –not just any old table, but an active piece, filled with memories of life and lively discussion

From Bernd Brunner, The Ocean At Home

By Rebecca Duffy, WPAMC Class of 2018

Leave a Reply