As the growing season comes to an end, the hay buying and selling season begins.

It’s still amazing how many round bales get sold on a per bale/roll basis rather than by weight. It’s a practice that almost always ends up with someone getting the short end of the stick.

I recall a Wisconsin project from a few years ago that involved a couple of extension agents going farm to farm weighing large round bales with portable pad scales. Prior to obtaining the actual bale weights, the agents and the bale owner estimated the average bale weight of the three bales that were weighed at each farm.

Overall, both the agents and farmers missed the actual average bale weight by 100 pounds, sometimes being over and other times being under the actual weight. The extension agents noted that there was not only large farm-to-farm variability but also extreme differences within bales of the same size located on the different farms.

In my own extension agent days, I used to help coordinate a quality-tested hay auction once per month. I would summarize the auction results and then post them on the internet.

Some sellers preferred to sell their hay by the bale instead of by the ton. This always meant that I’d have to estimate bale weight and convert to a price per ton because that is how the results were reported.

Initially, I dreaded doing this because I didn’t always trust the accuracy of my own guess, so I would always ask a few farmers what they thought. As you might expect, there were often wide ranges among those people who I would ask, leaving me to guess which estimate was the closest. Sellers would sometimes tell me that most people underestimate bale weight, and that’s why they like to sell by the bale if they can.

Multiple factors at play

There are a number of factors that can influence bale weight. They include:

• Bale size/shape

• Bale density

• Bale moisture

• Time of sale

• Forage species (grass or legume)

• Forage maturity (percent leaves and stems)

• Model and age of the baler

It’s fairly intuitive that size of the bale will impact bale weight, but what may be overlooked is the degree of change that occurs when a bale is only 1 foot wider or 1 foot more in diameter. The latter accounts for the largest change.

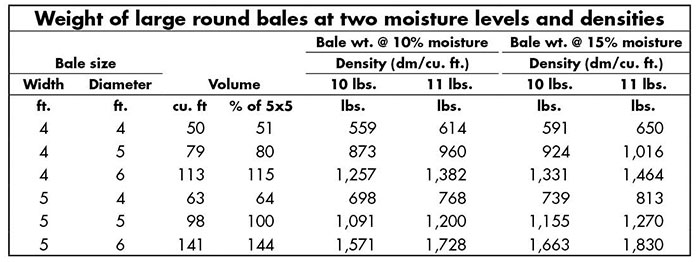

A bale that is 4 feet wide by 5 feet in diameter (4×5) has 80 percent of the volume of a 5×5 bale (see table). However, a 5×4 bale has only 64 percent of the volume of a 5×5 bale. Those percentages also translate to differences in weight if all other factors are equal.

Bale density also plays a rather large role in final bale weight. It often ranges from 9 to 12 pounds per cubic foot. In a 5×5 bale, the difference between 10 and 11 pounds of dry matter per square foot amounts to over 100 pounds per bale at both the 10 and 15 percent moisture levels. Missing the weight of a bale by 10 percent amounts to some pretty significant dollars when multiple tons are being purchased.

Forage moisture also plays a role in bale weight but to a lesser degree than bale density, unless bales are extremely dry or wet. Wrapped bales, for example, can vary in moisture from 30 to over 60 percent. When purchasing baleage, it is always recommended to either weigh the bales or have a rock-solid moisture test.

Time of purchase impacts bale weight in two ways. First, if you’re purchasing bales out of field, they are likely going to be at a higher moisture level and weight than they will be after being cured in storage. There is also a natural tendency for dry matter loss during storage that the buyer will incur if bales are purchased immediately after baling. As has been well documented by research, storage losses can range from below 5 percent to over 50 percent, depending on storage method.

Forage species also affects bale weight. Grass bales generally will weigh less than legume-based bales of similar size. This is because legumes such as alfalfa will make a denser bale than a grass species. In the previously mentioned Wisconsin study, the average weight of a 4×5 legume bale was 986 pounds. This compared to 846 pounds for grass bales of the same size.

Plant maturity is another factor that impacts bale density and ultimately bale weight. Leaves generally pack better than stems, so as plants mature and develop a higher percentage of stems to leaves, bales generally become less dense and weigh less.

Finally, there are many models of balers of differing ages. This variation, coupled with operator experience, lends further variability into the bale density and weight discussion. Newer machines are able to make a much denser bale than most older ones.

Given the number of variables that determine the actual bale weight, buying and selling large round bales based on a weight guess is likely going to result in a transaction that is either above or below market value. This can be extremely expensive for the buyer or seller, especially when a large number of tons are purchased over a period of time.

Weighing round bales might not be as convenient as not weighing them, but there are very few situations where a bale weight isn’t attainable. Take the time to weigh bales (all or a few) whenever a transaction is made.