Dan Severson, New Castle Co. Ag Agent; severson@udel.edu

Introduction

Quality of seed can vary greatly. The key to getting the best quality seed is to read and understand the information on the seed tag. Seed laws require that each lot is labeled to prevent misrepresentation of seeds offered for sale. This applies to a single species or a mixture, certified or non-certified seeds. Understanding the seed label will allow proper decision making when planning and installing a seeding.

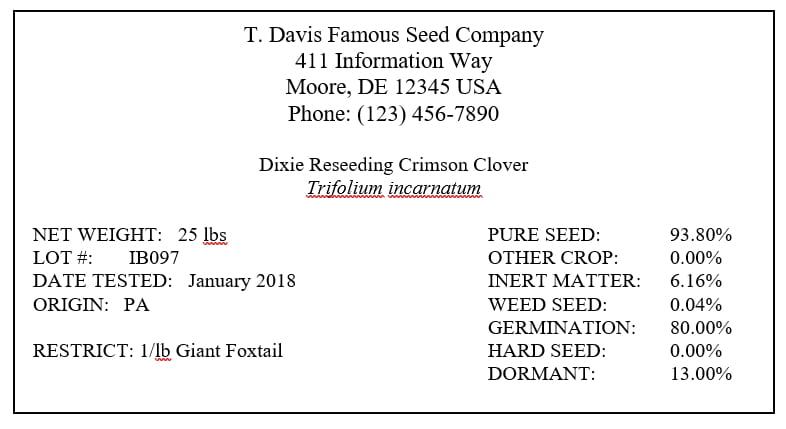

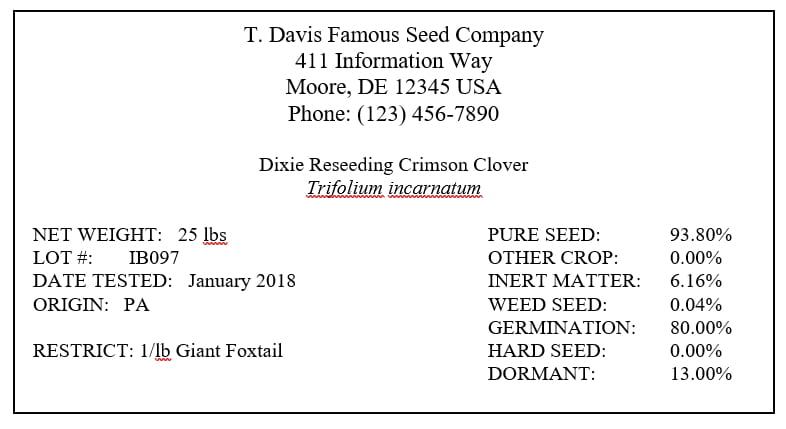

The Federal Seed Act (https://www.ams.usda.gov/rules-regulations/fsa) and the Delaware State Seed law Title 3 Chapter 15 (http://delcode.delaware.gov/title3/c015/index.shtml) specify the information required on the seed tag (see example seed tag on page 3). Seed tags are issued by the official seed certifying agency for each state. The Seed Laboratory of Delaware Department of Agriculture is the official seed certifying agency for the state of Delaware. All state certification agencies comply with the minimum requirements and standards of the Association of Official Seed Certification Agencies (AOSCA) (https://www.aosca.org/) to insure uniform testing methods and minimum standards of seed quality. Seed labels may vary from state to state, but all labels will have some semblance uniformity since the Federal Seed Act requires some information for interstate commerce.

Components of the seed label

- Type and Variety – Cultivar/release name, species, and common name;

- Lot number – a series of letters or numbers assigned by the grower for tracking purposes;

- Origin – where the seeds were grown;

- Net weight – how much material is in the container;

- Percent pure seed (purity) – how much of the material is actually the desired seed;

- Percent inert matter – how much of the material in the bag is plant debris or other materials that are not seed;

- Percent other crop seeds – other non-weed seeds;

- Percent weed seeds – seeds considered weed species;

- Percent germination (germ) – how much of the seed will germinate readily;

- Hard seed – seed which does not germinate readily because of a hard seed coat;

- Dormant seed – seed which does not germinate readily because it requires a pre-treatment or weathering in the soil (Some suppliers may combine hard and dormant seed on the label.);

- Germination test date – date should be within 12 months of the planned date for using the seed;

The date for how long the seed can be sold varies from state and type of seed. Delaware’s current time is 14 months, excluding the test date (total of 15). Most small packs of vegetable and flower seeds are marked packed for year 20?? They can only be sold for that year.

- Name and address of company responsible for analysis (seller or grower).

- Name of restricted noxious weed seeds (with number per pound of seed);

There are 2 types of noxious weed seeds – restricted and prohibited. Restricted weed seeds are listed as seeds per pound of material in the bag. There should be no prohibited weed seeds.

The restricted weed seeds for Delaware are dodder, bindweed, wild onion, wild garlic, corn cockle, horse nettle, cheat or chess, annual bluegrass and giant foxtail.

The prohibited list of weed seeds for Delaware are Canada thistle, quack grass and johnsongrass.

The prohibited and restricted noxious weed seed for Delaware are not the same as the Noxious Weeds list. Delaware currently has six noxious weeds: johnsongrass, Canada thistle, burcucumber, giant ragweed, Texas panicum and Palmer amaranth. https://agriculture.delaware.gov/plant-industries/noxious-weeds/

You may also see the following additional information on the label:

- Total Viability/Germination – this may or may not be stated. Total viability = Germination + Hard Seed + Dormant Seed. Total Viability may not equal 100%. This just means that some of the seed is not viable and will not germinate.

A typical seed label:

In addition to the seed analysis label, there may be a second label indicating the certification class of seed. The most typical second label would be blue and would indicate it as CERTIFIED SEED. Certified seed is the progeny of seed that has been handled to maintain genetic identity and purity and has been approved by a state certifying agency. Certified seed should be the first choice for any seeding project, especially when cultivars are used.

Using the Seed Label

- The total of Pure Seed, Other Crop, Inert Matter and Weed Seed should always equal 100%.

- If the purity or germination is very low, you may not want to use the seed.

- If there are noxious weed seeds, you should know what they are and whether they will be a problem on your planting site. You may not want to use this seed source because doing so risks introducing a problem.

- Always purchase and use seed based on Pure Live Seed (PLS). PLS is the amount of seed which will germinate and can be calculated using numbers from the seed label.

First, determine total viability

Viability = germination + hard seed + dormant seed

Viability is the percent of seed which will germinate, though it may not all germinate the first season. In our example, total viability = 93.00%.

Next, calculate the amount of Pure Live Seed (PLS)

PLS = (% Purity x %Viability)/100

In our example: PLS = (93.8 x 93)/100 = 87.23%

PLS can be used for calculating the amount of seed you will need to buy for a planting or when calibrating the output of a drill.

Bulk seed/acre = (lbs. PLS recommended/acre)/Percent PLS

If we want to seed 10 acres at 8 lbs. PLS/acre., then

(8 lbs. PLS/acre)/ 87.23% = 9.17 lbs. bulk/acre x 10 acres = 91.7 lbs. bulk seed needed .8723 PLS

Most native plant seed is sold on a PLS basis because germination and purity can be so variable. Always specify buying seed by the PLS pound to make sure you get the amount of seed you need. For example, percent germination rate of legumes is often lower than percent germination of grass species. Some of the cool-season turf-type grasses (fescues, orchard grass) and agronomic seed (oats, rye) are sold on the basis of bulk pounds only because germination and purity are typically very high and minimums are regulated by the Federal Seed Act.

Summary

The cheapest bag of seed is not always the best purchase. By understanding the information on the seed tag you can determine the quality of seed you are purchasing. By comparing the purity and percent germination you will be able to decide which bag of seed will produce a more successful, uniform and weed free stand.

Restricted and prohibited weeds vary by state and no seed can be sold if it contains prohibited weeds. Seed that is moved across state lines must meet the most restrictive state’s requirements. By monitoring the weed species in the lot, you can control what weeds are seeded in a planting.

Always order your seed as PLS seeding rate. Purity and germination percentages found on the seed tag determine Pure Live Seed (all seeding recommendations are given in Pure Live Seed rates) from which the bulk-seeding rate is calculated.

References

Englert, J.M. 2007. A Simplified Guide to Understanding Seed Labels. Maryland Plant Materials Technical Note No. 2. USDA-NRCS National Plant Materials Center, Beltsville, MD. 3p.

Kaiser, J. 2010. Reading Seed Packaging Labels (Seed Tags). Agronomy Technical Note – MO-38. Elsberry, MO.