This blog post is by Erica Lome, a student in the History of American Civilization Ph.D. program at the University of Delaware. This fall, she will be a Graduate Assistant at Nemours Mansion & Gardens.

A summer in Boston can really fly by when you’re exploring beautiful historic homes and encountering new types of furniture. My first blog post about my experience with the Boston Furniture Archive (BFA) covered only our orientation and the first few days of working at a site. Since then, we’ve visited four vastly different locations spanning distinct periods in American material culture. First, the 1749 Spooner House in Plymouth where one family lived for over 200 years. Then, onto the Bostonian Society (est.1881) located in the Old State House, where a dedicated group of antiquarians assembled to preserve the property and create a repository for objects significant to Boston’s history. Along the posh streets of Back Bay lay our next destination, the Gibson House Museum, a snapshot of Victorian domestic life circa 1860 untouched by modern museum interventions. Lastly, we recently finished a week at the Loring-Greenough House in Jamaica Plain, built in 1760 for Commodore Loring. While its gardens are used primarily as a public recreation space for the community, the house is often closed to visitors and contains both original objects and those collected by the historic Jamaica Plain Tuesday Club.

At these sites, we encountered English beds from the seventeenth century, ornately carved Renaissance Revival sideboards, Queen Anne tea tables, and reproduction Chippendales. While I’ve benefited tremendously as a historian from this experience, I have also learned a great deal about what it takes to manage, steward, preserve and interpret collections at small institutions and museums. Curators and board members alike were deeply invested in the holistic mission of their sites and provided us with records, inventories, and family histories so that we could view the objects we catalogued as part of a larger historic and personal narrative, rather than as isolated specimens.

That being said, the day-to-day work of cataloguing and photographing led to some unique learning moments. Rather than recap everything I did, I’ve decided to list some of the important and unexpected lessons I’ve learned which may benefit future scholars in the field.

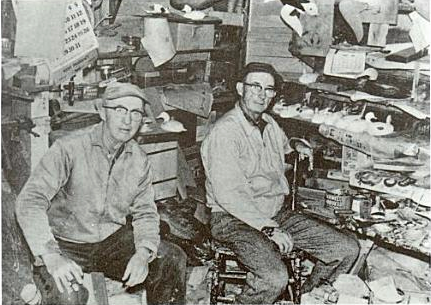

1) Space is nearly always limited. At the Bostonian Society, we worked in a narrow storage room, with chairs crammed into nearly every available corner. The Society started out collecting objects relevant to the interests of its founders, which included many nineteenth-century pieces. Presently, the Society is focused on building up its Colonial and Revolutionary-era collections, so many of the pieces formerly on view have been placed out of sight of the public. With these challenges, we had to be creative when it came to staging a photography studio, and flexible (literally) about moving around. We encountered similar space issues when it came to shooting furniture too heavy to move. You won’t always have a great space to work in, so come prepared to problem-solve!

Working in collaboration with the collection’s manager, we set up a tight but workable space for shooting at the Bostonian Society

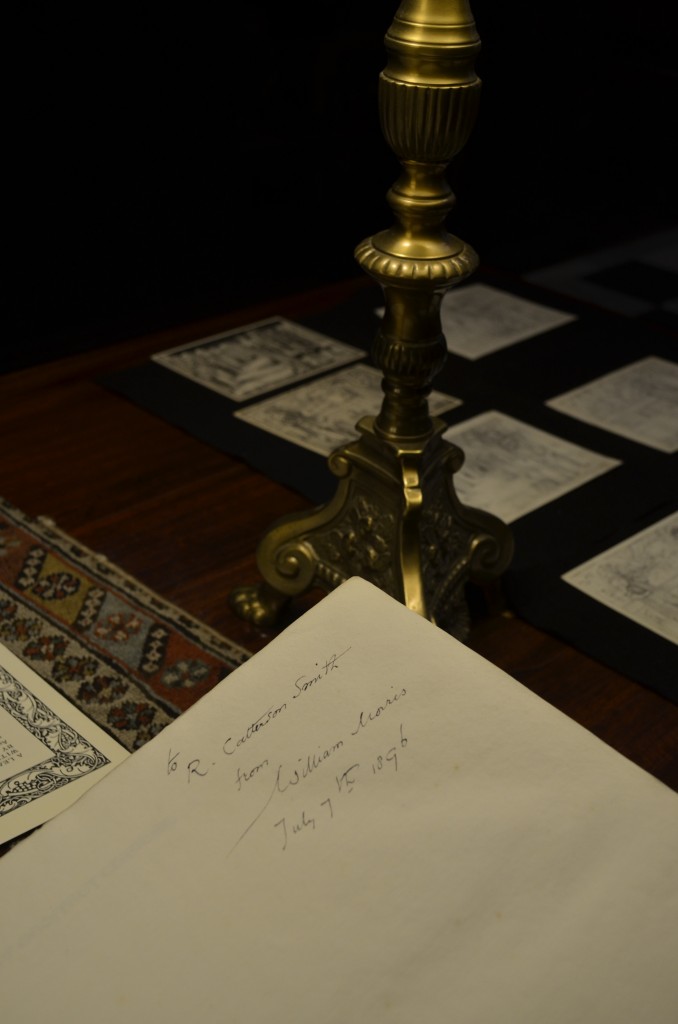

2) Furniture lies. A piece you thought you examined in one kind of light will end up having a bunch of marks (graphite numbers, signatures, chalk inscriptions) under the super-intense lights of the photo studio. Varnish, especially coatings applied during the late nineteenth to early twentieth-century, will disguise the wood grain and make identification difficult, or may appear to look deceptively like veneer. Additionally, a table that looks steady on its feet in the corner will turn out to have a pin loose, or is held together by some glue.

BFA intern Melissa examines each individual drawer for marks, while my nesting tables in the foreground turned out to have quite a few dowels loose

I found this chalk signature on the underside of a fall-front desk, after removing all the drawer components. Quite a surprise!

3) Be ready to face years and years of cobwebs built up in every nook and cranny. Likely, there will be some critter still crawling around and angry that you’ve disturbed their home.

4) Strength is key! We often joked that part of our training should have been a furniture boot camp, where we would deadlift armchairs and do squats with pedestal-base tea tables. In order to avoid straining our backs, we had to train ourselves to lift things the right way. Some pieces took all four of us to move, all while half-blind and maneuvering around obstacles.

An example of the diverse holdings of chairs from the Bostonian Society, and the problems their surroundings presented when it came to moving them.

5) Drink water, you fool! Summertime in Boston is no joke. You will likely one day work in a historic house with little to no air conditioning, and you’ll probably be working in the attic too. Our time at the Gibson house was punctuated by periodic water breaks and trips downstairs to the small fan for a moment of respite from the humidity. With the bright studio lights adding ten degrees to any space we were in, paying attention to our bodies was crucial.

A selfie taken in a moment of rest in between shooting at the Gibson House. Between the lights, carpet, and insulating wallpaper, it was a very hot stairway.

6) Communication and Collaboration. At the beginning of the summer, we worked in pairs to catalogue each object and photograph them. Once we grew more confident in our skills, we found it more effective to divide-and-conquer and work solo on smaller objects like chairs and side-tables. However, it is silly to think you alone can know everything there is to know about a piece of furniture. I still have trouble with wood identification, and frequently sought the advice of my cohort. Alternatively, I could helpfully point out the differences in a Federal (1795-1815) vs. Empire (1815-1840) example when asked. We also took turns consulting our traveling library, looking for similar examples to guide our decision-making. When it came to photographing stationary pieces like tall case clocks or secretaries, we all worked together to hold up white backdrops and brown felt to decrease the reflective glare on tabletop surfaces. Tiring work, but worth it for the catalogue-worthy picture.

7) Have fun! Once our group started clicking, we could approach our tasks with a good amount of levity and humor. Picture four tired, sweaty young women gazing with intense focus at a chair…inside of a thrift store with pop music blaring. After a day of moving and photographing (hot lights!), we took a well-deserved ice cream break and wandered into a local shop. Secondhand furniture lingered in the corner, and although it was clearly a reproduction, someone wondered aloud what kind of wood it was and the four of us leaned in for a beat of silence, faces screwed in concentration, and then we burst out laughing. Even in our off-hours, we still had furniture on the brain!

If this experience has taught me anything, it is to always be looking. Once you know how something is put together, or can recognize its stylistic influences, you see your material environment in a completely new way! One member of the BFA came to work sheepishly admitting she had spent the night before trying to figure out the wood of every piece of furniture in her bedroom; another claimed she couldn’t finish a movie set in the colonial era when she spotted an Eastlake piece in the periphery of the frame. As for myself, going with my mother through the famous annual Brimfield Antique Show became a chance to play “Antiques Roadshow,” to her delight.

With worksheets to transcribe and photos to edit, my summer in Boston will end on a more mundane note. However, I’m proud that my efforts will contribute to future scholarship and discoveries in the field of material culture. I return to the University of Delaware excited and prepared to tackle any new collections that come my way.

About the author: This blog post is by Erica Lome, a student in the History of American Civilization Ph.D. program at the University of Delaware. This fall, she will be a Graduate Assistant at Nemours Mansion & Gardens.

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)