By Elizabeth Jones-Minsinger

The first day of my graduate assistantship in the Manuscripts and Archives Department of Morris Library did not begin auspiciously. A truck carrying blank pennies had overturned on I-95 just north of our house, snarling traffic for hours on both the highway and local roads. I was already nervous to begin my archives assistantship because the work seemed so different from my own research, teaching, and scholarship. Having spent the last few years deeply entrenched in the specialized research and historiographical minutiae of my dissertation, would I be able to research a broad variety of collections and provide helpful access points to scholars? Would my knowledge of nineteenth- and twentieth-century history and materials be enough? Would I get crushed by the rolling stacks as I went to retrieve a box???

Luckily, I still managed to make it to the library on time and did not have to negotiate the rolling stacks on my first day. Throughout Special Collections, I found a wonderful community of librarians, archivists, and scholars and an outstanding repository of rare books, manuscripts, and ephemera. My own scholarship had brought me to Special Collections periodically over the years to research topics as diverse as eighteenth-century recipes, prisoner of war narratives, and household account books, so I already knew this was an incredibly rich repository.

However, I did not know just how much work went into making the collections available to researchers like me. The learning curve of this assistantship has been steep. Since September, I’ve been on a crash course in archival processing, learning to arrange materials, research and describe collections, and even encode finding aids. My first project exemplified the wide range of skills I would have to master. I was given a large, green, leather-bound manuscript and asked to provide a physical description, condition report, biographical and historical note, and scope of the contents. Relying on my limited knowledge of book construction and a healthy dose of Google searches, I completed the physical description of the manuscript fairly quickly. However, I quickly ran into an obstacle. The manuscript was a detailed volume of industrial weaving techniques from the late nineteenth century…in French. My knowledge of French is limited to two (essential) questions—how to get to the hospital and where to find the bathroom. However, I had some experience with textiles and their construction. Relying on cognates, similarities to Spanish, and Google Translate, I was able to muddle through.

In doing so, I discovered a fascinating story. The creator of the volume was J. Mercier, a student at the École Municipal de Tissage et de Broderie (Municipal School of Weaving) in Lyon, France. The school taught “the silk business” to the children of the Lyon’s residents, preparing them to be skilled weavers. Mercier likely created the manual, entitled “Cahier de Théorie,” to fulfill requirements during his third or fourth year in the program. In addition to lengthy discussions on the properties of various fabrics, Mercier included painstakingly detailed drawings of weaving patterns and diagrams for warping textile looms. Most pages of the volume are illustrated with multicolor drawings of repeating patterns and adorned with related fabric swatches. For my first project, I had been given a material culturist’s dream: a mixed media object that chronicled a craftsman’s acquisition of skill and expertise.

MSS 0097, Item 0174, J. Mercier, Cahier de théorie : notebook on weaving, Special Collections, University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware.

Following the Mercier project, I worked on several other French manuals related to textile production. Soon, I was also researching materials in German. For a brief moment, I was the expert in fin-de-siècle European industrial textile production manuals at the University of Delaware.

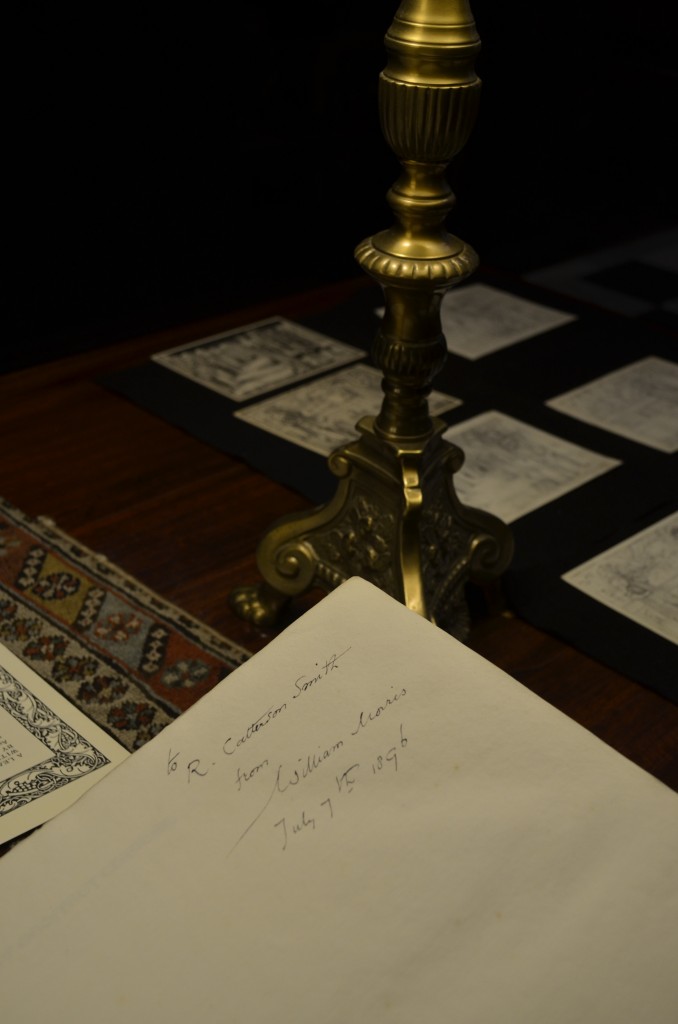

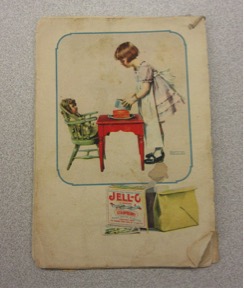

But I soon had to broaden my horizons once again. Since September, I have processed materials in French, German, Spanish, Latin, Italian, and, of course, English. My work has carried me to many times and places. I’ve processed a nineteenth-century devotional book created at a Catholic abbey in Ghent and a book casing constructed by a twenty-first-century paper conservator. I’ve read the accounts of itinerant Quakers, an American industrialist abroad, and a consumptive English poet traveling to Madeira in search of a cure. This assistantship has revived my interest in food history and allowed me to find a good home for my collection of gelatin ephemera (currently being processed by yours truly).

“It’s So Simple”: Jell-O, America’s Most Famous Dessert

The Genesee Pure Food Company, 1922.

University of Delaware, Special Collections

Formerly the Collection of the Author

I am now working on a processing plan for the U.S. Customs House papers from the port of Philadelphia, a collection spanning the 1790s to the 1930s. Once again, I’m encountering a steep learning curve, negotiating the myriad documents and specialized language generated by an expanding bureaucracy over three centuries. I’ve reconciled myself to the fact that I can’t be an expert in every collection I process. Instead, I need to rely on my research skills to identify reliable sources and make collections as accessible as possible to potential scholars. However, I’ve found that the Program in American Civilization has served me well, giving me a broader knowledge base than I realized I possessed and connecting me with a group of scholars willing to share their expertise when I’m out of my depth.

I look forward to further broadening my horizons in the coming months. And if you don’t hear from me for a while, PLEASE check the rolling stacks.

Elizabeth Jones-Minsinger is a doctoral candidate in the Program in American Civilization. For a sample of her work at the University of Delaware’s Morris Library, please visit https://library.udel.edu/spec/findaids1/view?docId=ead/mss0097_0084.xml