Upstate Stirpicults: Interpreting Childhood at Oneida

This post is part of a series of blogs completed for EAMC 606: Cities on a Hill: Material Culture in America’s Communal Utopias. This class examined the history and material culture of intentional communities throughout American history using Winterthur’s collections as well as field studies.

When most people talk about Oneida, they mention two things: the company made their mother’s silverware and the community practiced “free love.” Anything beyond that, particularly the connection between the two, is a mystery. This fall, Winterthur’s “Cities on a Hill: Material Culture in America’s Communal Utopias” class delved deeper into the history of the nineteenth-century intentional community. Besides our regular coursework, the class visited the Oneida Mansion House Museum on our tour of the utopian communities of Upstate New York. As the mother of a little one myself, I was particularly interested in the childhood experience in this unconventional setting and how it was interpreted in the museum.

A photograph of community members after a bee, c. 1870.

A photograph of community members after a bee, c. 1870.

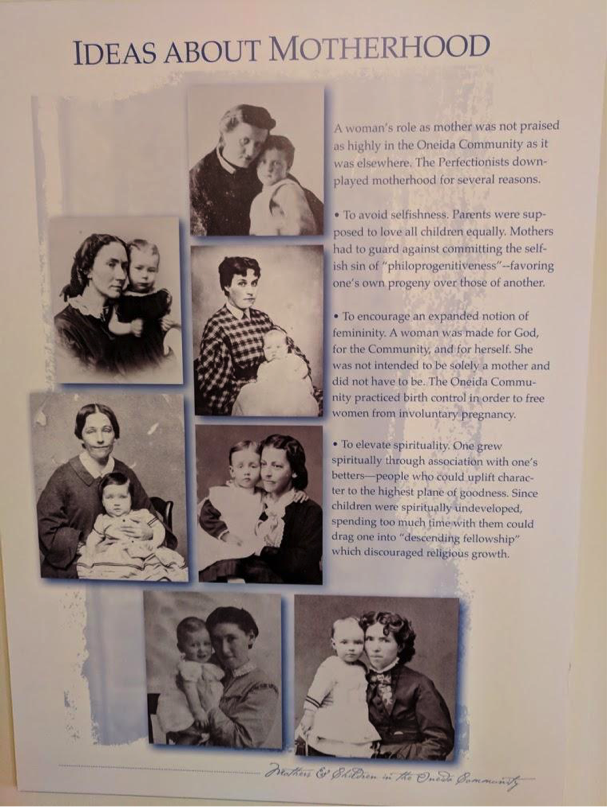

The Oneida Community practice of “complex marriage” stemmed from founder John Humphrey Noyes’ interpretation of Christianity known as Perfectionism. Noyes’ followers eschewed all selfishness, including exclusive relationships of all forms. To achieve this egalitarian social structure, Oneida Community members needed to overhaul traditional familial relationships. Under this new arrangement, each man ‘married’ every woman and vice versa. By extension, all adult were ‘parents’ to each child. Biological parents and grandparents lived separate from their offspring to keep them from developing exclusive, selfish attachments.

Main display of objects in the “Mothers & Children” exhibition

Main display of objects in the “Mothers & Children” exhibition

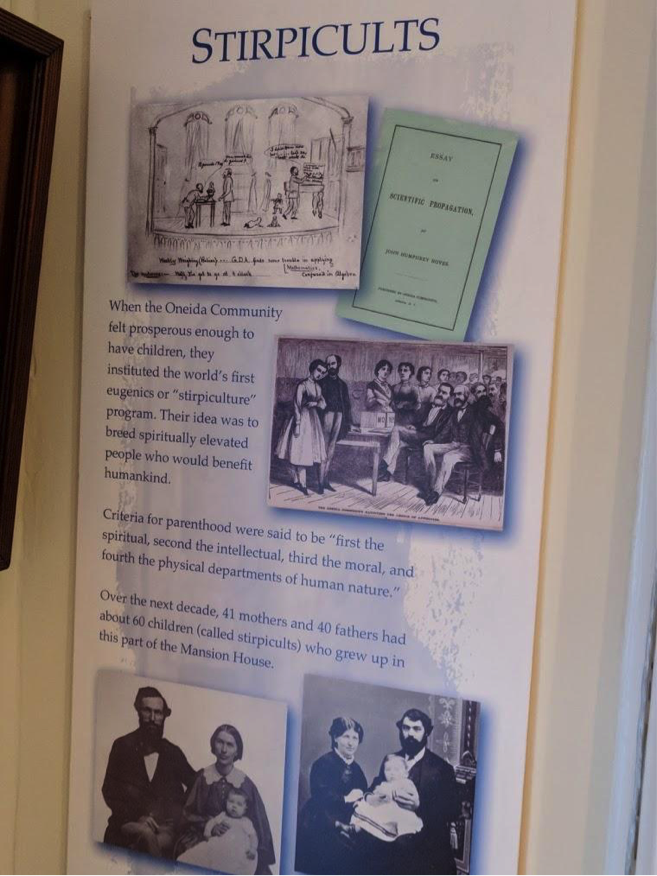

Despite their reputation for so-called “free love,” allegedly few unplanned children were born. Between 1869 and 1879, the Perfectionists began an experiment in “stirpiculture.” This brand of positive eugenics led to the planned conception and birth of fifty-eight selectively-bred children or “stirpicults.” Unlike the eugenics practices of forced sterilizations and abortions aimed at weeding out bad genes, stirpiculture encouraged breeding between people with desirable traits. The goal was to create genetically and morally “perfected” children. As fascinating as it may be to read about the Community’s unusual approach to relationships, the topics of sexuality and the ‘side effects’ of sexuality can be tricky to translate with physical objects to a mixed audience.

Being able to ‘step behind the stanchions” is one of best perks of traveling with Winterthur. This trip was no exception. Molly Jessup, the museum’s Curator of Education, tailored her tour to discuss the exhibitions from a museological perspective.

The exhibition “Mothers & Children in the Oneida Community,” held appropriately where the Children’s Department once stood, relies primarily on photographs and quotes from those who grew up at Oneida. Interpretive panels explain the structure of communal child-rearing succinctly and Jessup explained that in the usual tour the guide uses the space to explain stirpiculture.

Two of the “Mothers & Children” interpretive panels. These panels explain the main ideas behind the exhibition.

Two of the “Mothers & Children” interpretive panels. These panels explain the main ideas behind the exhibition.

Though it was interesting to see the clothing and toys used by the children, their role was more decoration than elucidation. Within the Children’s House, the community’s youth shared toys in common and were discouraged from claiming favorites as their own. In addition to having communal toys, the toys themselves underwent intense scrutiny to determine whether they encouraged inappropriate behaviors. The exhibition did not discuss how communalism was taught or that the objects were shared. Unfortunately, this problem is not uncommon in smaller house museums. Even with the many excerpts from the memoirs of the stirpicults, it is difficult to get a sense of how the objects on display fit into the larger narrative.

Close up of objects on main exhibition table.

Close up of objects on main exhibition table.

Being part of the Winterthur class tour, however, provided us with another uncommon experience: we had the chance to discuss the design of the exhibition with the curator. Jessup graciously discussed how they intend to integrate the objects into the conversation when the museum revamps the exhibition. As a future museum professional, it was a great opportunity to see how museums engage in self-reflection and address issues within permanent exhibitions.

Collection of toys on display. The labels state they were donated by former community members.

By Sharon Folkenroth Hess, University of Delaware, Museum Studies MA Program

Leave a Reply