Nathan Kleczewski, Extension Specialist – Plant Pathology; nkleczew@udel.edu

Over the past 5-6 years much progress has been made in producing varieties with moderate resistance to Fusarium head scab. Advancements in biotechnology and agricultural genomics have enabled university and industry researchers to produce varieties with better, more consistent resistance than those of the days when I had a much thicker, fuller head of hair. In addition, the newer moderately resistant varieties still yield well in the absence of head scab. This is an active area of research, and better varieties continue to be released.

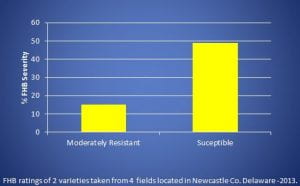

Below is an example of what planting a resistant variety can do. Last June an astute grower asked me to assess his wheat for scab. Below are the head scab severity ratings across fields planted with a moderately resistant and a susceptible variety.

FHB severity is one thing, but the most important part of FHB management is keeping mycotoxins at acceptable levels. If you want the best price for your grain, you want DON below 2ppm. Anything above that will likely get docked and in some cases loads can be rejected when levels are excessive. Interestingly, you can have symptoms of FHB, but your DON levels may not be high. DON results from the activity of the fungus, so the particular strain, chemotype, and environment all play a role in how much DON is produced. Thus, when you choose a variety you want one that helps keep DON in check. A quick look at the University of Maryland variety trial results for FHB provides an excellent example of the impacts of resistance on mycotoxins. These nurseries provide a more or less, “worst case” scenario for scab, with constant misting and FHB-infested corn kernels distributed throughout the nursery. The following is a brief summary of the 2012 and 2013 results:

Results from the UMD head scab variety evaluations is located at: http://www.psla.umd.edu/extension/extension-project-pages/small-grains-maryland

Due to how the resistance works, and an array of additional environmental, host, and pathogen factors, the apparent resistance can vary a bit from year to year or site to site. Overall, the resistance we see in our newer varieties is stable across environments or years, meaning, moderately resistant varieties consistently have much lower levels of DON than susceptible varieties. On average, moderately resistant varieties can cut down your DON by 50% compared to a susceptible variety. As you can see above, sometimes the difference can be far greater when you compare across many varieties. Take a minute and visit the UMD variety trial link posted above. You will notice that some of our popular varieties don’t perform so well in terms of DON. Where do your varieties fall?

Let’s consider the worst case scenarios for DON based off of the UMD variety trials in the following example. I’ve mentioned that on average, our best fungicides for scab, applied when conditions favor scab as fields enter flowering, get you on average 42-45% reduction in DON. If you planted the worst variety from the 2013 trials under those conditions you still would have around 13ppm DON AFTER making a fungicide application. Now if you had planted the most resistant variety and made a fungicide application, you would be around 2ppm DON. That’s right at the threshold. When you start with a resistant variety, and add in a fungicide such as Prosaro, Caramba, or Proline around flower when conditions are conducive for FHB, it increases the likelihood that you will not have loads outright rejected and improves your chances of selling your grain at a premium.

To finish, I want to show you, again, the results of 40 FHB management trials conducted over 7 states from 2007-2010. This work was published in 2012 in Plant Disease. As you can see, fungicide use on a susceptible variety gets you almost halfway there. However, it’s when you use a moderately resistant variety and a properly timed fungicide (if the environment is favorable for FHB) that you really can start to see a benefit.

FHB, like most plant diseases, requires an integrated approach to manage it. It is not like powdery mildew or leaf rust. Read my article on disease resistance from last week’s WCU to find out some reasons why this is the case. What we have for management is not perfect and we continue to look how to best manage the disease. We’ve come a long way from the, “rotate and plow” mindset of 10-15 years ago and no doubt will continue to make progress in managing this difficult to control disease in the future.