Richard Taylor, Extension Agronomist; rtaylor@udel.edu

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been called out to a couple of orchardgrass fields that are showing initial evidence of orchardgrass decline syndrome (ODS). This syndrome often results from a mix of several problems that develop on orchardgrass. ODS can be caused by one or more of the following problems: an imbalance between the rate of nitrogen (N) fertilizer and potash or potassium (K) fertilizer applied to the crop; an infestation by one or more pest species (white grubs, wireworms, billbugs, curculio, mites, thrips, aphids, and/or nematodes); mowing too close to the soil surface and leaving too little stubble for orchardgrass regrowth; and the development of a series of diseases such as anthracnose, septoria leaf spot, brown stripe, brown leaf blight, and barley yellow dwarf virus.

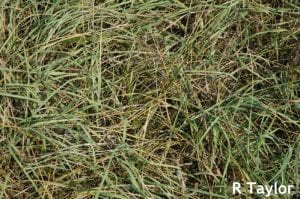

In the fields that I observed, the browning leaf tips and leaves (photo below) were an indication that the disease complex was present in the field. The real telling story however was where woods that were on two sides of the field blocked wind movement and resulted in higher humidity and longer periods of moisture on the leaves following dew or rain events. Near the wood line, the orchardgrass stand had been reduced by 95 to 99 percent with only a few small plants showing a few struggling small tillers.

Leaf symptoms on orchardgrass from a complex of diseases

Along some of the wood line, the stand loss extended only a few tens of feet into the field; but where the two sides of woods came together, the stand loss extended as much as several hundred feet into the field. This suggests that if anyone is interested in determining if they have a potential situation developing with ODS, they should evaluate the orchardgrass stand along wood lines or wherever the winds are blocked, resulting in longer periods of moisture on the leaves or higher humidity conditions. The excessive rainfall that we’ve had this year could have resulted in a number of fields at risk for ODS.

Now is the time to evaluate orchardgrass fields to determine if it will be necessary to replant the field early this fall. The best thing to do would be to rotate to another less susceptible grass crop or to rotate completely away from grass hay if there’s a market available to you for legume (such as alfalfa) hay. No matter what the decision is, you should take a soil test for the field to determine the K status. Inadequate soil K levels have been linked to the disease especially when a lot of N fertilizer is applied to boost hay yields.