Speaking of Speakeasies: Baltimore and Prohibition in Collective Memory

By Rachael Kane, ’22

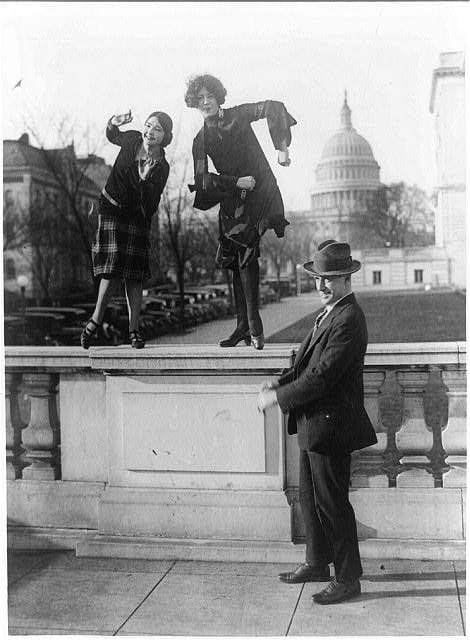

For many people, the 1920s hold a uniquely enticing historical appeal. Steeped in carnivalesque imagery of flappers, suffrage marches, speakeasies, and jazz music, the charm of the roaring twenties often obfuscates the underlying political unrest of the era.

Figure 1: Rep. T.S. McMillan of Charleston, S.C. with flappers, Miss Ruth Bennett and Miss Sylvia Clavins, who are doing the Charleston on railing, with U.S. Capitol in background. National Photo Co., Charleston at the Capitol. 1920-1930. Library of Congress. https://lccn.loc.gov/93508925.

One of the clearest examples of this type of misdirection is prohibition and its relationship to other narratives of urbanization, race, and the redefinition of American morality.1 The common distortions in the pervasive memory of this period present an interpretive challenge for historic sites: How do we both celebrate the popularity of the roaring twenties while also emphasizing the long-term effects and consequences of this era?

One way to help contextualize this series of events is to utilize surviving interior spaces that remain functional: they often draw tourist interest while also offering opportunities for visitors to form deeper connections. During a summer field study trip, Winterthur students visited the Owl Bar in Baltimore, Maryland. We were all deeply taken by the quirky, turn-of-the-century space.

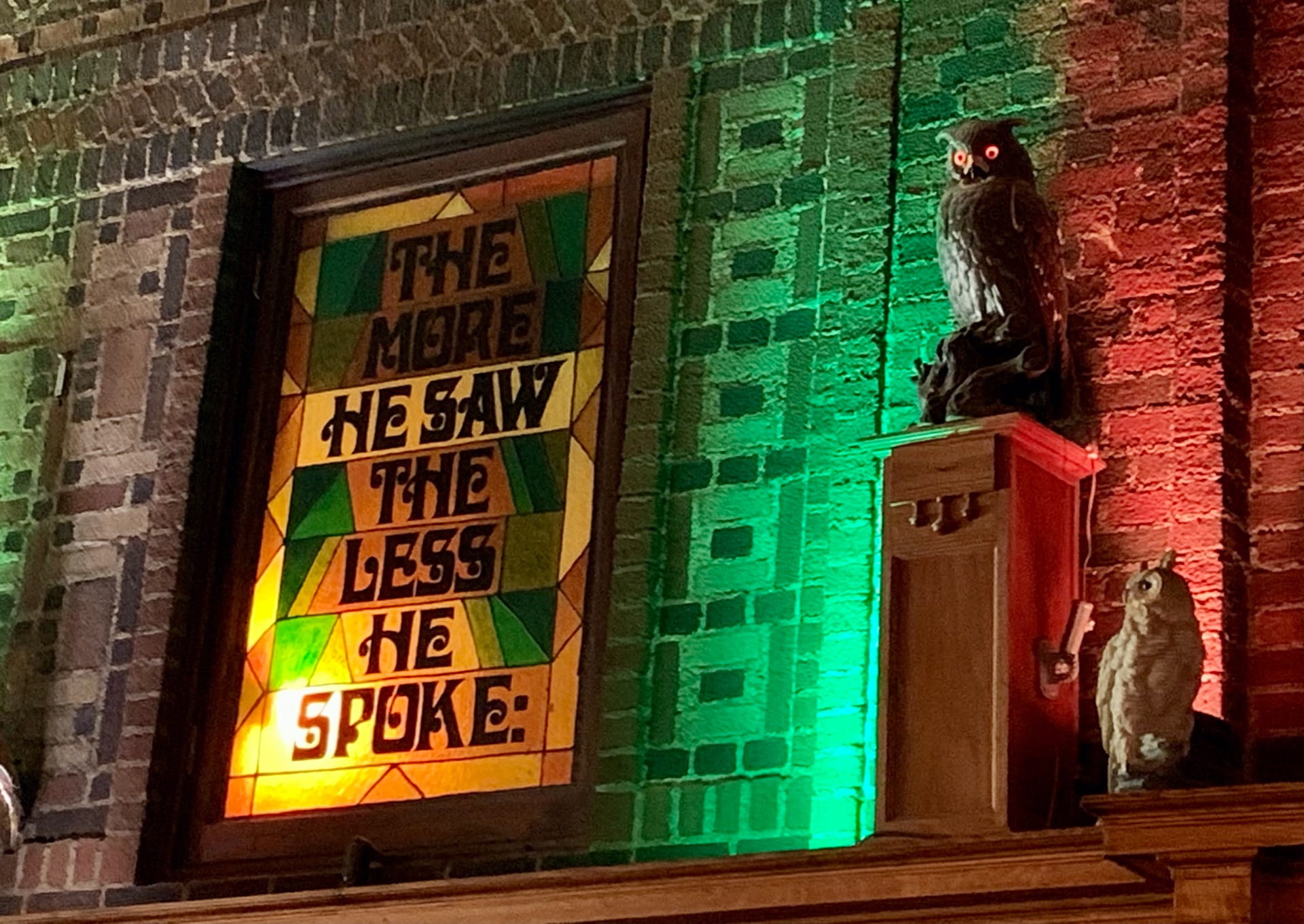

Figure 2: This is one of the stained-glass windows used for decoration in the bar. Image taken by author.

Like many twentieth-century maritime ports, Baltimore had a significant liquor and grain trade prior to prohibition.2 The industry held such importance that Maryland, as a state, passed few laws enacting the federal prohibition mandate and enforcement was uneven.3 This led to a prolific underground liquor industry including a number of prominent speakeasies such as The Owl Bar, located in the Belvedere Hotel, which opened in 1903.4 Originally known simply as the bar room, the moniker “Owl Bar” came from the decor which featured statues and stained glass windows depicting owls. During prohibition, the eyes of the owl statues would light up, signaling an incoming police raid and allowing knowledgeable patrons to hide or discard their drinks.5

Figure 3: This is one of the owl statues with illuminated eyes used to signal arriving raids. Image taken by author.

The architecture and decorative history of this space are inherently part of its appeal as a destination bar in the city. The bar harkens back to Maryland’s unique relationship to prohibition and provides a satisfyingly scandalous narrative that aligns with the popular view of the thrilling and subversive culture of the 1920s. How can places like this both maintain their status as fun and functional cocktail bars while also paying homage to their own complex histories? What narratives about prohibition should we be highlighting in our cultural institutions?

The early twentieth century saw the incredible gains of the suffrage movement, but it also saw the growing influence of racially targeted “Jim Crow” laws. In 1904, one year after the bar opened, Baltimore adopted segregated street cars, and in 1910 the city enacted discriminatory housing laws which would become the underlying structure for the modern urban landscape.6 Prohibition itself was a divisive issue within Black communities.7 For some, liquor served as an economic resource. However, many prominent civil rights leaders, including Frederick Douglass, were strongly in favor of prohibition.8 They feared that drunkenness, or even simply the perception of drunkenness, would be weaponized against Black individuals in order to unfairly incarcerate them or to accuse them of being a burden on society.9 We encountered Black history at several other sites in our field study trip, including at the Maryland State House. However, Douglass was largely addressed as an extraordinary individual, rather than as part of a larger narrative of Black activism. One exception to this was the Reginald F. Lewis Museum, a space dedicated to the history of African Americans and their role in social justice, activism, and community building in the Mid-Atlantic region. These critical stories were often left as secondary notes to the contributions of white activists during the early twentieth century, omitting critical understandings of the development of Black activism.

However, even after the laws were enacted, they did not have the intended effect. Instead, during the campaign for prohibition, Black people were barred from larger temperance movement groups.10 Furthermore, the ultimate failure of prohibition led to significant death tolls from imbibing poorly produced bootlegged booze, as well as racially motivated policing strategies that targeted Black and immigrant neighborhoods while ignoring similar violations in white areas.11 As a visitor to the Owl Bar, I wondered who would have been seated in the space, and to what extent the warning flashes in those owlish eyes helped protect the diverse community of Baltimore, or if they only reinforced existing racial prejudices in the city.12

The fun-fueled and whitewashed history of the prohibition era minimizes Black activists’ contributions to the movement while erasing the adverse effects of the era on non-white and immigrant populations. Baltimore and the Owl Bar represent a city in the process of reinventing itself in the modern era. More than just a wink and a nudge from a stained-glass window, this bar can remind us of the realities of police brutality, the birth of twentieth-century American activism, and the failure of the “Noble Experiment” of prohibition. While many of us enjoy a good speakeasy-themed bar, it is worth considering which people are included in our shared memories of the roaring twenties, and how cultural and historic sites can do more to bring awareness to the layered narratives hidden behind the bar room door.

- In this case, prohibition refers to the 1920-1933 ban on producing and selling alcoholic beverages federally enacted by the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act of 1919. ↩

- Hays, Jo N. “Overlapping Hinterlands: York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, 1800-1850.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 116, no. 3 (1992): 299. ↩

- Kelly, Jacques. “Baltimore looked the other way during Prohibition,” The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, MD), April 30, 2010. ↩

- To learn more about the Owl Bar, their history, and their connection to the Belvedere Hotel, visit their website here: https://www.theowlbar.com/. ↩

- Lennon, Beth. “The Owl Bar in Baltimore, Maryland,” National Trust for Historic Preservation. October 30, 2014, https://savingplaces.org/stories/historic-bars-owl-bar-baltimore-maryland#.YO3kZBNKj2Q. ↩

- Laws of the State of Maryland. Department of Legislative Reference. 1904: 186. This law established “separate but equal” accommodations for street cars as a state-wide mandate for Maryland ↩

- Lieb, Emily. “The “Baltimore Idea” and the Cities It Built.” Southern Cultures 25, no. 2 (2019): 104. ↩

- Schrad, Mark Lawrence. “The Forgotten History of Black Prohibitionism,” Politico. February 6, 2021. https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/02/06/forgotten-black-history-prohibition-temperance-movement-461215. ↩

- Douglass, Frederick. “Temperance.” Speech, 1870s. Library of Congress,https://www.loc.gov/item/mfd.32022/. ↩

- Yacovone, Donald. “The Transformation of the Black Temperance Movement, 1827-1854: An Interpretation.” Journal of the Early Republic 8, no. 3 (1988): 290. ↩

- García-Jimeno, Camilo. “The Political Economy of Moral Conflict: An Empirical Study of Learning and Law Enforcement under Prohibition.”Econometrica 84, no. 2 (2016): 521. ↩

- Malka, Adam. ““The Open Violence of Desperate Men”: Rethinking Property and Power in the 1835 Baltimore Bank Riot.” Journal of the Early Republic 37, no. 2 (2017): 196-200. ↩

Leave a Reply