An Intimate Meeting by Candlelight: Remote Learning at Winterthur

By Alexandra Izzard, ’22

Since March of 2020, our lives have changed dramatically: no more dropping into collections, spending long hours crowded around a library table, or traveling around museums in groups. How do students of material culture connect with objects in a world of Zoom lectures, virtual conferences, and remote research? So many of the fundamentals of object-based learning are made dangerous by COVID-19, but the professors, curators, and staff at the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture have gone above and beyond to give students the richest experience possible. Though lectures are online, fellows are given every opportunity to safely visit the objects in the collection, institutions are giving out more scholarships for virtual conferences than it is possible to take advantage of, and instructors are always willing to meet with you to figure out how to make your wildest research dreams a reality.

During our Prints and Paintings block, I approached curator Stephanie Delamaire with such a dream. Curious about 18th century mezzotints, I wanted to explore the concept of tactility, which had occurred to me while conducting research in the rare book archive at Winterthur. The Winterthur collection contains the second edition of John Evelyn’s famous treatise Sculptura (1755) which walks readers through the history of printing; a singular mezzotint is inserted within its pages.1 Evelyn talks about the “illustrious touching” of the artist in the creation of the print, encouraging readers to have their own tactile experience with the mezzotint.2 His words led me to imagine gathering around this object with fellow print enthusiasts, touching it, enjoying the experience of not just looking.

I wanted to recreate a part of this experience with a mezzotint, looking at it in period-accurate lighting rather than the bright, artificial light of a collection study room. I asked Stephanie if I could bring a mezzotint home to look at it in daylight and candlelight, and she was immediately supportive of my slightly outlandish request. Since it isn’t possible for me to remove an object from the official Winterthur collection and introduce it to a potentially dangerous environment in my home, we scoured Ebay for a cheap print but were met by the predicted reality of steep prices.

Turning towards resources within our own institution, Stephanie connected me with Joan Irving, Senior Paper Conservator of the Winterthur Museum. She generously lent me a 1741 mezzotint portrait of Thomas Birch, created by John Faber the Younger, from her lab’s collection. The likeness depicts Thomas Birch, an English historian and Trustee of the British Museum, dressed in a white powdered wig, a white stock, and a dark, billowing robe, lightly holding a book ajar and gazing over his right shoulder.3 Though the subject is certainly interesting, I was more concerned with the materiality of the print, so the next step was to consider the lighting under which it would have been observed in the 18th century.

Since this print was viewed in an album, flat on a table, it could have been seen through both filtered indoor light and artificial light, likely from a flame.4 A survey of scholarship led to the conclusion that that the print should be examined in direct sunlight, indirect sunlight, light from a chandelier, light from flame through glass, and light from a bare candle.5 Since the lighting was dictated by the confines of my apartment, the daylight was through the panes of 1929 metal casement windows with northern light, dimmed LED bulbs were used in the chandelier, a candle was placed in a 19th century lamp for the glass filtered light, and an assortment of beeswax candles were used for the bare flame.

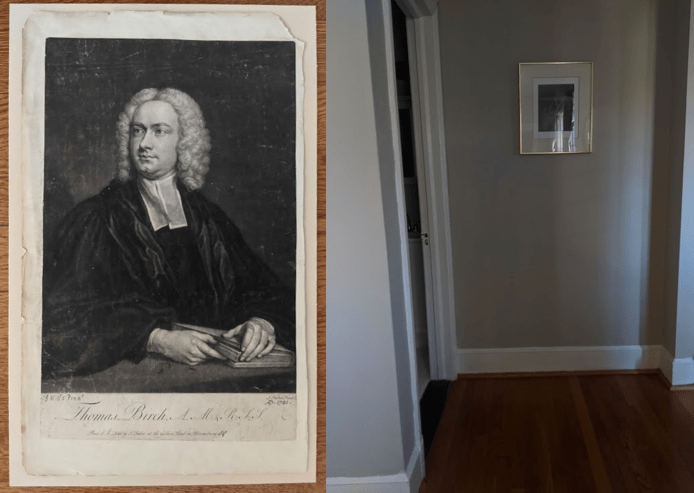

Examining this print in direct sunlight, its many flaws and relatively medium quality were quite evident. I could see the wrinkles in the paper, the scratches on the surface, and places where it has been later marked. The velvety blacks of the mezzotint were not very strong – the sitter appeared fuzzy and slightly undefined, ghostly in the bright light (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Thomas Birch Print, John Faber the Younger after J wills, 1741, mezzotint on paper, British, in direct sunlight partnered with an image of the lighting source.

Much of the same held true in darker, less direct daylight (Figure 2). However, the darkness brought out the dark in the mezzotint, beginning to conceal the fact that it was lighter, and likely more in the middle of the run.

Figure 2: Thomas Birch Print, John Faber the Younger after J wills, 1741, mezzotint on paper, British, in indirect sunlight partnered with an image of the lighting source.

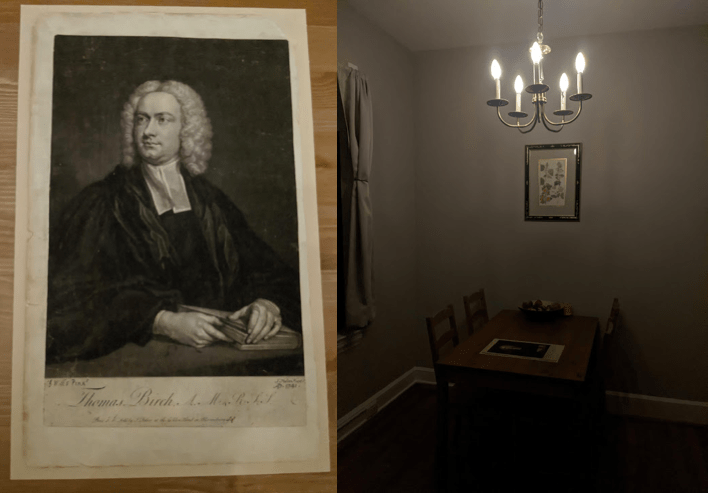

In dim chandelier light, the focus moved from the darkness of the ink to the lightness of Thomas Birch’s features (Figure 3). The print became much more animated as the focus moved to him as an individual rather than the subject of a print.

Figure 3: Thomas Birch Print, John Faber the Younger after J wills, 1741, mezzotint on paper, British, in chandelier light partnered with an image of the lighting source.

Lit by the flame encased in glass, the mezzotint took on a new life. The reddish glow of the glass of the lamp cast a color onto the sitter while the flickering light seemed to animate his face. The details of the print suddenly disappeared, and I was met with an almost mobile figure of a man. Though the detail of the craft was lost, the animation of the subject was gained (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Thomas Birch Print, John Faber the Younger after J wills, 1741, mezzotint on paper, British, in glass-filtered candlelight partnered with an image of the lighting source.

Finally, lit by candles, there existed a middle ground between the indirect sunlight and the darker light of the glass lamp. The detail of Birch’s face was preserved while the movement of the light brought it to life (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Thomas Birch Print, John Faber the Younger after J wills, 1741, mezzotint on paper, British, in light from a bare candle partnered with an image of the lighting source.

Broadly speaking, this experiment made clear that light changes the perception of a print. In daylight, I was able to analyze the print more as an object, seeing flaws, additions, and technique in the plates. As the print progressed into darkness, it became more of a personal object, something to interact with on an intimate level, something to converse with, something that could consume one’s entire world. The subject came to life, making the print a more dynamic object. This experiment in lighting led to research into who would have seen these prints in each lighting scenario, where they would have seen them, and what prohibitive factors may have stood between individuals and access.6 Though I returned to fairly conventional research questions, the unconventional path I took to reach them, open flames and all, led to a more nuanced and genuine understanding of their lived experience. Though we are in a time of unfamiliar modes of learning, creativity and unyielding professorial support have led me to ask exciting new questions of my research.

References and Further Readings:

Cooke, Lawrence S. Lighting in America: from Colonial Rushlights to Victorian Chandeliers. Pittstown, NJ: Main Street Press, 1984.

Dillon, Maureen. Artificial Sunshine: a Social History of Domestic Lighting. London: National Trust, 2006.

Early Lighting: a Pictorial Guide. Boston: The Rushlight Club, 1972.

Evelyn, John. Sculptura : or, The History and Art of Chalcography, and Engraving in Copper: with an Ample Enumeration of the Most Renowned Masters and Their Works. To Which Is Annexed, a New Manner of Engraving, or Mezzotinto, Communicated by His Highness Prince Rupert to the Author of This Treatise. 2nd ed. London, England: Printed for J. Payne, 1755.

Mayor, A. Hyatt. 1980. Prints & People : A Social History of Printed Pictures. Princeton Paperbacks. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Moss, Roger W. Lighting for Historic Buildings. Washington, D.C.: Preservation Press, 1988.

The British Museum. “Thomas Birch, Biography.” Collections Online | British Museum. Accessed November 1, 2020. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG84830.

Wax, Carol. 1990. The Mezzotint : History and Technique. New York: H.N. Abrams. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG84830.

- Evelyn, John. Sculptura : or, The History and Art of Chalcography, and Engraving in Copper: with an Ample Enumeration of the Most Renowned Masters and Their Works. To Which Is Annexed, a New Manner of Engraving, or Mezzotinto, Communicated by His Highness Prince Rupert to the Author of This Treatise. 2nd ed. London, England: Printed for J. Payne, 1755. ↩

- Evelyn, Sculptura, 128. ↩

- The British Museum, “Thomas Birch, Biography,” Collections Online | British Museum, accessed November 1, 2020, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG84830. ↩

- The print has evidence of binding holes, so it can be deduced that this mezzotint was originally bound in an album. ↩

- In order of reference: Roger W. Moss, Lighting for Historic Buildings. (Washington, D.C.: Preservation Press, 1988).; Early Lighting: a Pictorial Guide. Boston: The Rushlight Club, 1972.; Maureen Dillon, Artificial Sunshine: a Social History of Domestic Lighting (London: National Trust, 2006).; Lawrence S. Cooke, Lighting in America: from Colonial Rushlights to Victorian Chandeliers (Pittstown, NJ: Main Street Press, 1984). ↩

- Mayor, A. Hyatt. Prints & People: A Social History of Printed Pictures. Princeton Paperbacks. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1980. 514. ↩

Leave a Reply