Through the Eyes of the World’s People: The Materiality of Visiting Early Shaker Villages

By Christopher Malone, ’21

“Having heard of various accounts of the very singular mode of worship practiced by the people called Shaking Quakers, I this day went to visit them.”

-Moses Guest, Sunday October 10, 1796

Woodcut showing a view of Hancock Shaker Village, founded in 1790 by the Shakers in western Massachusetts. The village contains a stone round-barn built in 1826, one of the only round barns made by the Shakers. The barn can be seen at the back of the image to the right. Photograph of Woodcut, Hancock Shaker Village, Massachusetts, Gelatin, SA 368 a-b, The Edward Deming Andrews Shaker Memorial Collection, Courtesy, Winterthur Library.

The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, or Shakers as they came to be known, were so peculiar to people during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, that a cult of visitation grew up around their earlier villages of Watervliet, Hancock, Tyringham, and New Lebanon. The Shakers both discouraged and encouraged visitors to tour their villages. They saw visitation as a means to proselytize outsiders, who they called the World’s People; strangers who didn’t share in their beliefs. People came from all over to see how they lived, how they dressed, how they worked, and how they worshipped. The Shakers hoped that by allowing the public to visit, they might dispel outsider’s erroneous beliefs about their religious practices and ascetic lifestyle. For instance, some outsiders believed the Shakers danced naked or sacrificed children during their religious rites. Regardless of their opinions of the Shakers before or after visiting, outsiders generally had favorable accounts of their cleanliness and order, the style and layout of their architecture and villages, and the serious nature with which the Shakers comported themselves among strangers.

When visitors wrote about the Shakers, it was usually to explain their curiosity and to tell someone else what they had experienced. Most wrote with some sort of prejudice or malice, while others were just ignorant to Shaker religious practices and their chosen lifestyle. Some visitors knew the Shakers intimately, perhaps after visiting numerous times or through a friend or family member who was a Believer. Others knew very little. These were the people who perpetuated wide-spread myths about the Shakers. Visitor accounts were published in letters to family and friends, in newspapers, and in travel journals. Visitors came from all over the world, but most came from surrounding villages and towns in New York and New England. The Shakers welcomed some very prominent visitors including writer James Fenimore Cooper, author and statesman Horace Greeley, president of Yale College Ezra Stiles, and English writer and social critic Charles Dickens.

Why Had They All Come

Visiting Shaker villages was first and foremost a sort of public sideshow, a curiosity that one could experience while taking in the waters at the popular Lebanon Springs resort, or on the way to Albany for business. Visitors began hearing of the Shakers almost immediately, and by the 1820s, their peculiar ways and lively Sabbath services were well-known. The spectacle of dance brought many outsiders out on a Sunday afternoon, and the ritual didn’t usually disappoint. Visitors saw first hand how industrious the Believers were with their oval boxes, flat brooms, and time-saving inventions. They could walk away with various products being made on the premises. Often, visitors came because they knew someone within the village or one of their relatives was a Believer. Some were interested in joining the society while others came because the Shaker’s accepted what some called “Winter Shakers.” These were people who professed interest in joining the society, but would often leave when the weather became nicer. Visitors who came were overwhelmingly wealthy individuals who could afford to travel up the Hudson River to the many spa towns and resorts in Upstate New York. Sometimes, Europeans taking a “Grand American Tour” visited the Shakers. Others were literary scholars or social critics writing about the benefits or detriments of communal living. Still others were poor, down-on-their-luck individuals looking for free room and board. Many visitors who experienced Shaker culture remain anonymous, lost to time.

Shakers dancing inside the meetinghouse, women and men danced separately, while Shakers of different ethnicities and races danced together. Shakers near Lebanon by Nathaniel Currier, 1823-1888.

Outsiders best encountered Shaker culture through the materials and objects they experienced while visiting. Visitors often recalled the way in which the Shaker Brothers and Sisters were dressed. Some were pleased with their plain clothes, while others derided their old fashioned outfits as archaic relics of the past. Shaker architecture and landscapes were revered and pleasing to the eye. Their straight lines and geometric symmetry were said to give off an air of prosperity to many in the outside world who couldn’t understand how people this “well off” could live this simply. The most unifying belief surrounding the Shakers was that they provided some of the best meals visitors ever ate. Praise was lauded on the bread and butter and on the quantity and quality of the food served. Most visitors remarked on the incredible attention the Shaker sisters gave while waiting on them at the dinner table.

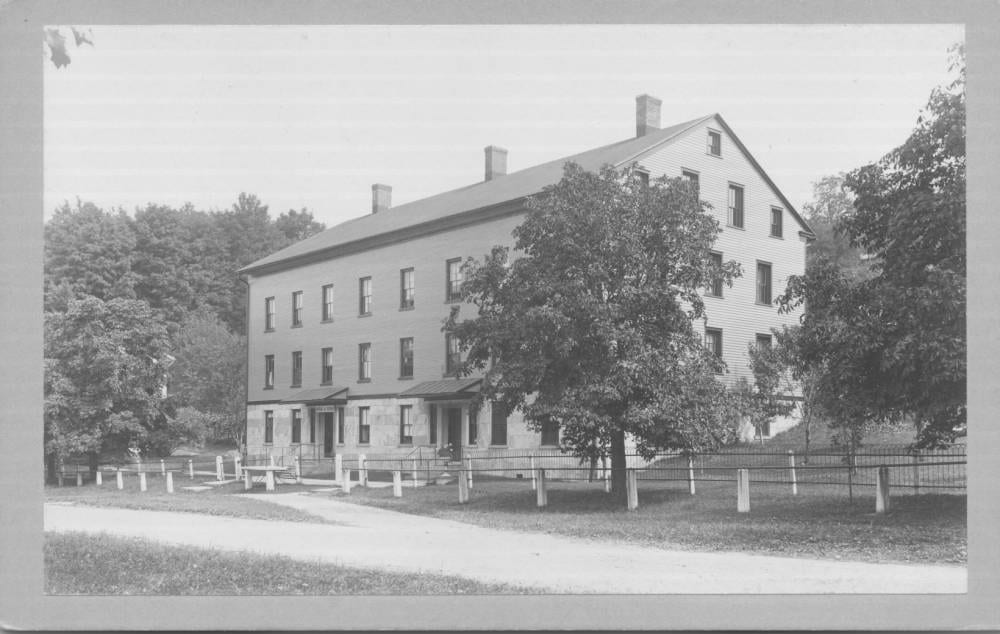

Most visitors came to the Trustees’ Office to purchase goods, have dinner, or stay overnight. Trustees’ Office, New Lebanon Shaker Village, New York. The Edward Deming Andrews Memorial Shaker Collection, Courtesy, The Winterthur Library

The tête-à-tête between the Shakers and the World’s People caused the Believers to develop their seemingly insular world around public sentiment. For example, Shaker elders codified spiritual dance into a more choreographed set of movements because of the endless ridicule by outsiders. In the 1840s, this led to the suspension of public worship and public meals for a short time until they were more comfortable opening themselves up to public opinion. Finally, the Shakers systematized “touring the village” by introducing the Trustees’ House in the early nineteenth century, making this building a repository for visitors who were more than willing to commodify the Shakers by buying their goods as a token or souvenir of their visit. The material culture of visitation was so ingrained in the expectations of outsiders. The cult of Shakerism can be traced to these early Shaker villages and the visitors who popularized them. By writing about their encounter with the Shakers and Shaker material culture, these outsiders immortalized the United Society of Believers into our cultural memory and tangible world.

Leave a Reply