View Finding: Thomas Davies and the Assault on Fort Washington

The objects at the Winterthur Museum are inspirational. This is not a new idea. Duncan Phyfe dining chairs, silver teapots, and Staffordshire creamware have stimulated questions and thoughts in the minds of the museum’s material culture fellows since the program’s inception in 1952. During my first semester as a Lois F. McNeil fellow, one object inspired me to travel to New York.

Hanging on the wall of the sixth floor of the museum is an ink drawing tinted with watercolor made by Thomas Davies in 1776. The drawing depicts the British and Hessian assault of Fort Washington, an American fortification located on the heights at the northern end of Manhattan Island. The battle took place on November 16, 1776. Davies, a captain in the Royal Artillery and an eyewitness to the battle, executed this drawing soon after the assault. The loss of Fort Washington resulted in a massive American surrender, precipitating the Continental Army’s abandonment of Fort Lee on the palisades across the Hudson River and its despairing retreat through New Jersey.[1]

A View of the Attack against Fort Washington and Rebel redouts near New York on 16 of November 1776 by the British and Hessian Brigades. Thomas Davies, 1776, Ink and Watercolor on Laid Paper, Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, DE, Museum Purchase

A View of the Attack against Fort Washington and Rebel redouts near New York on 16 of November 1776 by the British and Hessian Brigades. Thomas Davies, 1776, Ink and Watercolor on Laid Paper, Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, DE, Museum Purchase

The focus of Davies’s drawing is the topography in which the assault took place. Prior to the American Revolution, Davies trained at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich, England. At Woolwich he learned geometry, the technical aspects of artillery, and how to draw. Before photography, military drawings served as functional records of battles and landscapes.[2] Drawings provided perspectives of elevation, terrain, and sightlines that maps could not. With the landscape in front of him, Davies recorded the assault, detailing the rocky heights and lower farm land around Fort Washington. As I looked long and hard at this drawing, a few questions came to mind: How did Davies choose his viewing location? Does his drawing faithfully record the landscape? Why was this site important enough to record? My fascination with Davies’s creation of this drawing inspired me to travel to New York and view, first-hand, the landscape he saw 238 years ago. I hoped that my personal engagement with his drawing would help me understand its creation.

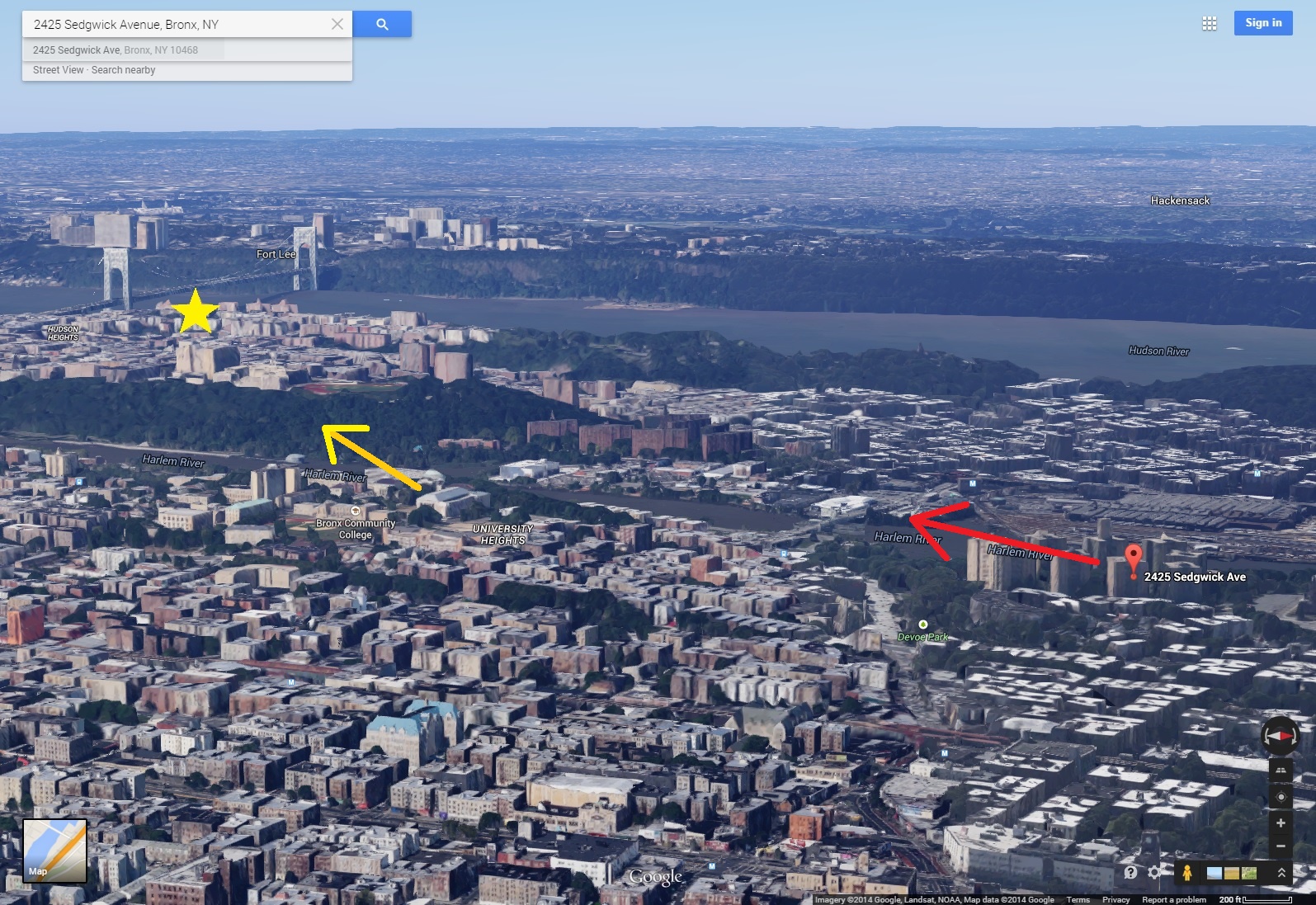

I first needed to figure out Davies’s location. The Continental Army built Forts Lee and Washington about where the George Washington Bridge is located today. With the Hudson River and New Jersey palisades visible in the background of the drawing, Davies shows the assault as viewed from the northeast. In the foreground of the drawing is the Harlem River, meaning Davies stood in what is today the Bronx. In order to see such a broad view of the landscape on the west side of the river, he must have stood on elevated ground. In consultation with modern topographical maps of the Bronx, there are two significant rises above the Harlem River to the northeast of Fort Washington, known as University Heights and Kingsbridge Heights. I planned to explore these two areas and take photographs of the views to figure out if my placement matched Davies’s location.

Topographical map of Manhattan Island and the Bronx. The heights are visible along both the Harlem River and the Hudson River. Star marks approximate location of Fort Washington. This map is courtesy of National Geographic: http://maps.nationalgeographic.com/maps

Topographical map of Manhattan Island and the Bronx. The heights are visible along both the Harlem River and the Hudson River. Star marks approximate location of Fort Washington. This map is courtesy of National Geographic: http://maps.nationalgeographic.com/maps

In preparation for my trip, I employed Google Maps, especially the Street View function, to find spots on each of the heights with unobstructed views of Manhattan Island. The amount of trees made this difficult. On October 13th, my first stop would be the Bronx Community College located at the crest of University Heights. While trees did partially obstruct my view from the College’s Hall of Great Americans, I was able to see the geographical features across the river that Davies included in his drawing. I could see the tops of the support towers of the George Washington Bridge, I could see the heights where Fort Washington stood, and I could also see the areas of Manhattan Island with lower elevation. However, the viewing angles did not match Davies’s drawing. I was in a spot that was east-northeast of Fort Washington, not quite northeast. To correct this, I decided to head north to Kingsbridge Heights.

View from the University Heights. Photo by author.

View from the University Heights. Photo by author.

My searching on Google Maps provided me little hope of finding an unobstructed view of Manhattan from Kingsbridge Heights. However, as I walked north on Sedgewick Avenue on the south end of the heights, I came upon a two level parking deck that would put me just above tree level, mimicking the unobstructed view Davies had in 1776. After receiving permission from the parking deck attendant, I went up to the second level to see what I could see. When I made it to the top I knew I found the view. The angles roughly matched. The landscape was recognizable. I could see the New Jersey Palisades in the distance, as well as the high ground that is now the location of the Cloisters. The Harlem River flowed in the foreground of my view. I could also see my previous location, University Heights, to my extreme left, matching the location of the cannon battery on the extreme left of the drawing. Therefore, the southern end of Kingsbridge Heights seems to be the approximate viewing point Davies used to draw the assault.

View from the Kingsbridge Heights. Photo by author.

View from the Kingsbridge Heights. Photo by author.

By placing himself on the Kingsbridge Heights, Davies had a broad view of the northern Manhattan landscape. If he chose to draw from what is now the University Heights, Davies would have been viewing the landscape on more of an east-west axis, minimizing his ability to convey the north-south situation of the heights on Manhattan Island. Taking the view from the northeast allowed him to see the length of the heights across the Harlem River. From the Kingsbridge Heights he could also include each body of troops involved in the assault. Seeing this area with my own eyes helped me to understand why Davies chose this spot. It provided him with the best vantage point to convey the distance, depth, and terrain of the landscape.

The difference between the viewing angles from the University Heights (yellow) and the Kingsbridge Heights (red). Star marks approximate location of Fort Washington. Pin marks my location. Image courtesy of Google Maps.

The difference between the viewing angles from the University Heights (yellow) and the Kingsbridge Heights (red). Star marks approximate location of Fort Washington. Pin marks my location. Image courtesy of Google Maps.

My trip also confirmed the topographic accuracy of Davies’s drawing. The comparison images I include below show the corresponding features that have not changed significantly in 238 years.

The matching features. Images courtesy of Winterthur Museum and the author.

The matching features. Images courtesy of Winterthur Museum and the author.

Seeing this landscape first-hand conveyed to me its former strategic significance. It is topography, after all, that encouraged the placement of Fort Washington and turned the area into a battlefield. In relation to the Hudson River, fortifying the rocky heights of Manhattan provided a commanding presence on the waterway. These heights rise nearly two hundred feet above sea level. By dislodging the Americans, the British and Hessians took control of not only the heights of the island, but also the adjacent section of the Hudson. Such a significant action on a strategic landscape gives reason for this drawing and its emphasis on topography.[3]

In one sense I performed experimental archaeology on my trip. I went where Davies went and saw the topography he saw. I walked up the hills that Davies climbed. Time separated our experiences. It is personal engagement with objects that can be helpful to gain insights about their creation and use. Other examples of this type of engagement include working clay on a potter’s wheel to understand the techniques and difficulties of pot construction or feeling the rhythm of a spinning wheel when making wool thread. Although these experiences occur in a modern context, they can still be moments of learning inspired by objects that have stories to tell.

Today, the sounds of trains, car horns, and residents animate northern Manhattan. However, in 1776 this landscape became a battlefield, as musket and cannon fire echoed through the heights. However, the rocky heights have not changed much since British and Hessian soldiers assaulted Fort Washington. In comparison with Davies’s drawing, it is still a recognizable landscape.

[1] R.H. Hubbard, ed., Thomas Davies (Ottawa: The National Gallery of Canada, 1972), 46 and 58.

[2] Hubbard, Thomas Davies, 60; Jim Burant, “The Military Artist and the Documentary Art Record,” Archivaria 26 (Summer 1988): 33-34, accessed October 20, 2014, http://journals.sfu.ca/archivar/index.php/archivaria/article/viewFile/11491/12435.

[3] The fort was renamed Fort Knyphausen for the Hessian General Wilhelm von Knyphausen, Hubbard, Thomas Davies, 60.

By Matthew Skic, Winterthur Program in American Material Culture, Class of 2016