The Art of the Book: Bookbinding at Colonial Williamsburg

On Sunday morning, the last day of our field trip to Colonial Williamsburg, our class split into two groups—one headed off to the Wigmaker’s shop, while the rest of us went to the Bookbinder’s. Located in a small, one-room, unassuming frame building just off of Duke of Gloucester Street, the bookbindery business represented by Colonial Williamsburg was originally established by William Parks. Having first been a book publisher in England, Parks immigrated to America in the 1720s. He originally settled in Annapolis, Maryland—where he started a printing press and founded the Maryland Gazette newspaper in 1726. Around 1730, he established the printing press on Duke of Gloucester Street in Williamsburg.

Bookbinder Dale Dupree discusses the history of the bookbinder’s shop in Williamsburg.

Our guide for the visit, bookbinder Dale Dupree, told us about the various roles the bookbindery played during the 18th century. It functioned as a stationer’s, post-office, advertising agency, a newsstand, and a bookbindery, in addition to being a printing press. Like many other trade shops in Williamsburg, the bookbindery needed to serve a variety of functions—since relying on the bookbinding trade alone was not an option due to the high cost of bound books and the lack of demand for such items.

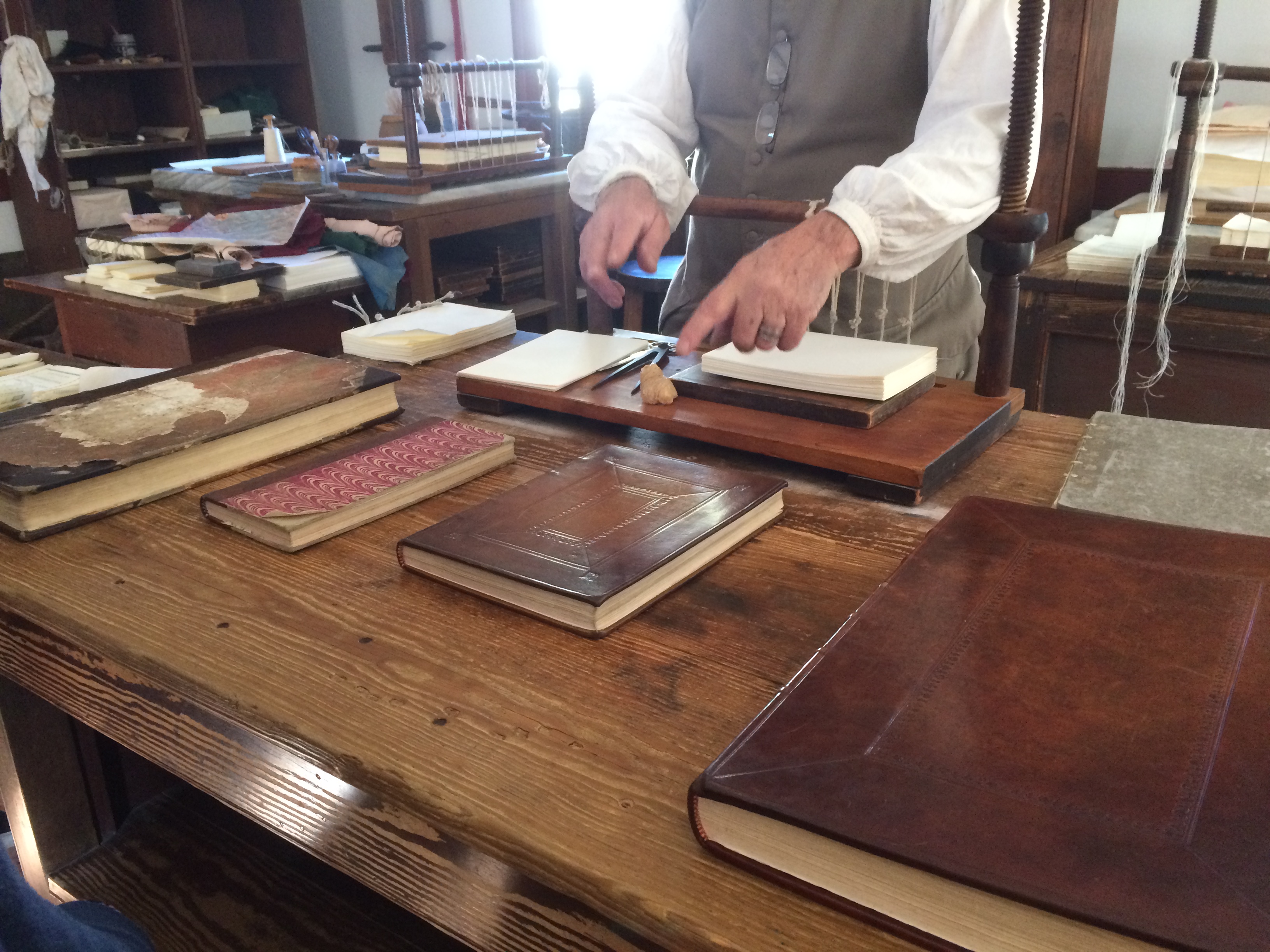

Examples of the different sizes of bound books sold in William Parks’ shop.

During the colonial era, the bookbindery in Williamsburg never sold printed books. Instead, the local market demanded blank bound books, sold in an assortment of styles—including ledgers, waste books, and account books. Each of these books were available in many different sizes and binding finishes. Dupree showed us a variety of blank bound volumes, and discussed the most noticeable difference between these blank books—their sizes. The most common sizes were folio, quarto, and octavo, all made from the same size of paper. Folio books were made by folding a piece of paper once to form two leaves (or four pages)—resulting in a folio. A quarto-sized book had four pages of text on each side of the paper, which, folded twice, creating eight leaves of text. An octavo book had eight pages per side of paper, and when folded three times, produced a sixteen-page gathering. Thus the naming convention for book sizing is correlated to the number of pages per side of paper.

The bookbinder group attempts to align margins.

In order to get a better sense of how bookbinders created books, Dale gave us each two printed sheets of paper that, when folded correctly, came together as the children’s nursery book Tom Thumb’s Play-Book. The pages of the story were printed with eight pages per side of paper, creating a 32-page, pocket-sized book. Dale told us when folding our paper the most important thing was to match the margins of the text, rather than the edges of the paper. The edges can be trimmed with a special tool to cut off the waste (a plow)—but if the margins are misaligned the text will be cut off.

The gatherings of Tom Thumb’s Play-Book prior to being bound.

After the group successfully folded the pages of our children’s books, we each had two “gatherings” of paper that needed to be bound together. Dupree taught us the easiest and most affordable way to bind books. We punctured three holes along the folded side of our gatherings with an awl. Using flax thread we bound our books together with a kettle stitch—the stitch ended on the backside of the book, and we tied off the thread with a simple knot. Dupree told us many books would have been finished this way in colonial America. A simple exterior binding, with no cover, made the printed material more affordable to a wider audience—allowing the dissemination of knowledge more cheaply.

UD Ph.D. student Kyle VanHemert binds his book.

So where did Williamsburg printers get their paper? Perhaps unsurprisingly, the industrious William Parks established a paper mill outside of Williamsburg. Parks travelled to Philadelphia—the papermaking center of the colonies—and enlisted the help of Benjamin Franklin to establish the first paper mill in Virginia. The mill was only in operation from about 1743 to 1750, when Parks died. However, the craft of papermaking was never terribly successful in this region, and Virginians relied heavily on paper imported from England.

Winterthur Fellow Allie Cade applies paste onto her paste-paper

For our second activity, Dupree had us try our hand at making paste-paper. Paste-paper was a cheaper alternative to the marbled paper commonly used as decorative endpapers. Dupree told us that in Europe during the 18th century the Dutch were responsible for most of the printed material. They helped popularize the marbled endpaper used by designers to mimic stone—hence the name marble paper.

Paste paper was faster and less expensive to produce, and still resulted in a designed look. All that was required to create our designs was water, flour, and the dye cochineal. Dupree mixed up the ingredients, and demonstrated how to apply the red paste to the paper. He took a special tool with carved teeth and made a wave design by scratching away the paste from the paper, exposing white lines. While I was unsuccessful at making the pattern Dupree demonstrated, I think I came up with a pretty pattern of my own. The paste-paper was then hung over a rope in front of the fire to dry.

Examples of the different leather used in the book binding trade.

Lastly, Dupree pulled out several pieces of treated leather and discussed the variety of finishing options a bookbinder might choose. He showed us sheep leather, calf, and Morocco leather. Sheep leather was the most inexpensive binding option, and typically lasted about 100 years. Leather from a calf costs in the 18th-century twice as much as sheep leather, but would last twice as long. Morocco leather was the best, softest, and most pliable leather. It was often made of goatskin, and carried the heftiest price tag—costing twice as much as calfskin.

Dale Dupree demonstrates how to plow the waste edges of the books.

Bright, clean, and well lit with large amount of natural light, the workspace of the bookbindery was one of the most enjoyable stops on the trip. It was a great way to start the last day of studying craft—starting with two large sheets of paper and finishing with a tiny and aptly named pocket-sized book.

.

By Catherine Morrissey, Ph.D. Candidate, University of Delaware Department of Historic Preservation

.

For many years, the Department of Historic Trades at Colonial Williamsburg has generously hosted Winterthur students as part of a course in pre-industrial craftsmanship. Over the course of several days, we students work closely with the tradespeople, trying our hands at a wide range of eighteenth century occupations that bring our studies, quite literally, to life. Every year, we leave with a deeper understanding of the material world. This post is part of a series that chronicles our visit in March, 2017.

this is good