Seats of Power: Comparing Thomas Constantine’s Chairs

When you have the opportunity to put two chairs made in the same cabinetmaker’s shop around the same time together, what might you find? Students in the Winterthur program are thrilled when we come across objects that help enrich the stories of other objects through comparison. Through analyzing their constructions, not only can we discern possible information about a shop or a region, but we can use the comparisons to raise questions about larger themes throughout history.

United States Capitol after the burning of Washington, D.C. in 1814. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

On November 2, 1819, the New York Daily Advertiser reviewed the recently unveiled House of Delegates Chamber at the United States Capitol. Of the furniture, they wrote, “We are told it was executed by Mr. Constantine of New York by contract, and is said to be equal to anything of the kind for strength, solidity, and excellence of workmanship, manufactured in the United States.” The furnishing marked a significant stage of completion for the Capitol, which had met with several obstacles in its construction, including the burning of Washington, D.C. by the British in the War of 1812. The cabinetmaker of this new set, Thomas Constantine, had finished upwards of 200 chairs for the House in just over a year and would go on to complete a set of 48 chairs for the Senate by the end of 1819.

Chair, Thomas Constantine and Co., New York, NY; 1819. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, maple, brass. 65.00106.000, Courtesy of the United States Senate.

At Winterthur, another chair made by Thomas Constantine shares many similarities to the armchairs made for the use of the Senate. The chairs would almost be twins, if not for some crucial differences. It is these small changes in carving, construction, and changes made over their lifetimes, that we must pay attention to in order to understand the individual contexts in which they were commissioned and functioned.

Armchair, Thomas Constantine, New York, NY; c.1819. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, white pine, maple, brass, leather. 1998.009, Courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Garden, & Library.

As material culturists, we have to ask the question: was the armchair in the Winterthur collection created by Constantine before or after his Senate commission? Perhaps more importantly, why should we care? By understanding one cabinetmaker’s shop, we can hope to better understand the greater world in which they were operating. Had Constantine created the Winterthur armchair after his Senate commission, he might have been using his most famous commission as advertising. Had it been created beforehand, it may have been a template for what would later furnish the nation’s capitol.

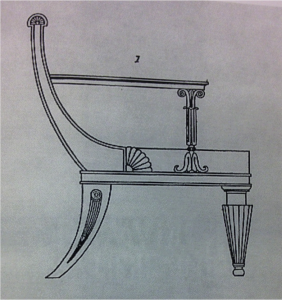

Without documents, students of material culture do what we learn to do best: look at the objects that survive. There are unique details to Winterthur’s armchair not found in the surviving Senate armchairs. Though some Senate chairs have since lost their arms, remaining details closely match an image in Thomas Hope’s Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (1807). Though not a pattern book, Household Furniture would serve as one of the go-to fashion source for classical revival furniture, a style popular in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries inspired by the empires of the ancient world. The Winterthur armchair has similar lines, but with more simplified carving. This can be seen in the lesser number of reeds on the front and back legs.

Thomas Hope, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (1807), pl. 59, no. 1. Courtesy of the Winterthur Library.

The Winterthur armchair could have been crafted similar to the Senate chairs for several reasons: as a means for Constantine to profit off of his most famous commissions, a way to accommodate the taste of his clientele, or even an economic choice to create a chair based on a model his shop would be familiar with. Details aside, the armchairs have one thing in common: they both stand as symbols of power, indicating wealth and status through material and ornamentation. The Winterthur armchair is almost entirely made of mahogany and would have sent a clear message of its owner’s wealth and social status regardless of its relationship to the Senate.

By comparing only the appearances of two chairs with very different histories, we begin to explore these assertions of power identity from the government to the home. Whether as representatives of power of the nation, or power of the private citizen, Constantine’s chairs mark a valuable statement made across the early United States.

By Michelle Fitzgerald, WPAMC Class of 2017.

Leave a Reply