Love by the Sackful

Dorian Cole, WPAMC ’24

It hurts to be a mother. My own mother told me that women forget the pain of childbirth. How else, she asked, would we ever be convinced to do it again? Pain can be hard to remember, but blurry memories turn sharp in other ways. How do you hold a memory without cutting yourself on its edges? The things that hurt us hurt to think about even years removed from them, even across generations. When we do remember our pain, we often fail to articulate it. Elaine Scarry famously described “the tendency of pain not simply to resist expression but to destroy the capacity for speech.”1 Often, suffering silences. After all, how can we talk about hurt without reproducing it?

This is a question historians of enslavement think about a lot. When their stories are told, enslaved people are described as victims. Extrapolated from a thin archive that consists almost entirely of writing by their enslavers, thousands of names merge into a single Black experience, characterized by suffering and dehumanization. Of course, their lives were bigger than that, filled with hard choices, beautiful memories existing alongside the ugly ones. Most importantly, they loved each other. They acted on that love, in big and small ways, every day. Sometimes history is just a word for the memories that got written down. If the only memories about your family that got written down were written by the people who hurt you, then they become a history of that hurt. To tell a different story, we need different sources.

Tiya Miles’ All That She Carried tells the story of one such source, a feed sack from South Carolina in the 1850s. Ashley’s sack, as it is now called, has a profound effect on visitors to the Middleton Place House Museum. Senior curator Mary Edna Sullivan recalls handing out tissues to guests. Likewise, the institution’s former vice president Tracey Todd once confessed, “I cry when I read it aloud.”2 By it, she meant the short paragraph stitched in elegant red letters onto the sack’s front:

My great grandmother Rose

mother of Ashley gave her this sack when

she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina

it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of

pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her

It be filled with my Love always

she never saw her again

Ashley is my grandmother

Ruth Middleton

19213

Ruth’s words transform the object into an archive of its own. In stitching out what happened to her family, Ruth engaged in a powerful act of remembering. Perhaps knowing that no historian of her time would do it for her, she boldly wrote her own history. Moreover, she wrote a history that acknowledged suffering while insisting adamantly on love. In addition to carrying the objects listed in her inscription, Ruth makes it clear that Ashley’s sack also carried Rose’s love for her daughter and the memories they shared.

Miles too insists on love, arguing that love was an act of resistance to a cruel system that sought to dehumanize Rose and her daughter. When Miles first presented her research for this book at the 2019 Modern Language Association conference, scholar and quilter Kim Hall commented, “I’m frustrated because I don’t know how to talk about love” and speculated that perhaps by locating “love in the archive,” scholars could begin to talk about the love that existed in the lives of Black people.4 That history of capital L Love–the same capital L Love that Ruth memorialized in her needlework–is often erased in favor of a focus on suffering, the memories of Black life in America reduced to often unspeakable histories of harm or presented didactically to white audiences. Stuck behind glass and under the stewardship of white curators, the presentation of Ashely’s sack at the Middleton Place House Museum risks falling into this trap. The sack, packed to the brim with Rose’s love and hope, only seems to inspire tears.

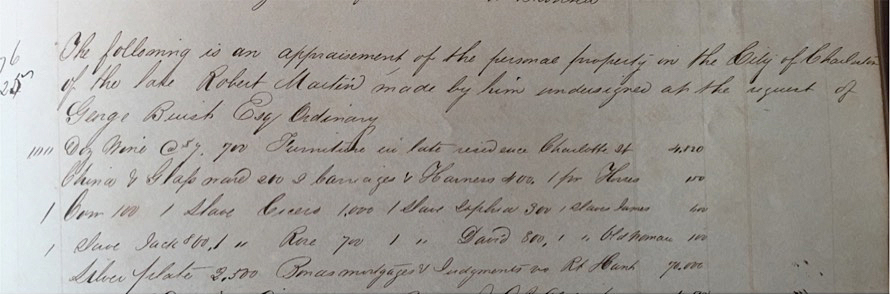

South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

Conscious of the archival absences created by systemic racism and slavery, Miles combines a material culture analysis of Ashley’s sack with an innovative reading of more traditional sources to reinsert love into the archive. In doing so, she not only makes the historically marginalized stories of Black mothers visible and immediate, but also highlights the resilience and agency of these women.

While Rose’s story was tragic, it was not only tragic. At times, it could even be triumphant. Rose gave her daughter pecans, an exotic nut compared to the much more common local chestnuts. Even if she was a cook with greater access to the plantation’s food supplies, taking these pecans would have put Rose at great risk. In her 1859 memoir, the free black woman Eliza Potter recounted how enslaved people, near starving, would resort to stealing from the plantation’s food supplies. “If they are not caught, they are smart;” she wrote, “and if they are, they are punished.”5 We do not know if Rose was smart or punished. In all likelihood, she was both. But when she learned her daughter would be sold away from her, she was determined to provide her with something to hold onto, to eat, maybe even to plant as a seed someday. Rose stole those pecans from the kitchen she worked in and, whatever happened to Rose next, Ashley received them and lived to tell the tale to her granddaughter as a free woman, many years later. Those “3 handfulls of pecans” made Ashley’s sack a cornucopia, so full it inspired Ruth to add an extra L to the word handful.

Many of the items placed in the sack follow this pattern, at first appearing meager and sad, but actually signifying a life-affirming resilience communicated from mother to daughter. For instance, though it was tattered, the dress Rose gave to Ashley was likely precious, carrying with it a heavy symbolic connection to bodily autonomy. Within the system of slavery, which sought to exert complete control over Black women’s bodies, acts of self-care involving hygiene and beauty could be revolutionary. Sumptuary laws attempted to control how enslaved people dressed, using fashion as a visual language to affirm intertwined race and class boundaries. In 1735, section 26 of South Carolina’s slave code bemoaned that “many slaves in this Province wear clothes much above the condition of slaves, for the procuring whereof they use sinister and evil methods” and listed the types of inferior material enslaved people should be wearing.6 The existence of these laws suggests that rather than capitulate to these markers of inferiority, enslaved people took pride in their appearance, using their clothing to blur the boundaries sumptuary laws were trying so hard to enforce. In this context, Rose’s gift to Ashley–a tattered dress, a dress that may have been Rose’s first before being handed down–is also a message: you get to dress yourself.

Finally, we come to Rose’s braid. Human hair is often associated with Victorian mourning jewelry. While its inclusion in the sack does speak to some amount of grief at their separation, rather than a symbol of death, the braid symbolized the unbreakable connection between mother and daughter. Hairwork, jewelry finely crafted from the hair of deceased loved ones, signified the lasting connection between the dead and the living and the hope that they would someday be reunited in heaven. This association translates easily to the forcible separation of Rose and Ashley. That said, hairwork was primarily worn by white people. For many enslaved people, hair was instead associated with conjure bags, cloth sacks used to provide magical protection in their syncretic religious practices. Certainly, the material similarities between a conjure bag, packed with symbolic items that created magical protection, and Ashley’s sack, packed with equally symbolic items that offered tangible physical protection, are striking. Hair was also one of the many sites of struggle between Black women’s autonomy and white enslaver’s sense of entitlement to their bodies. Some slaveholders sought to control hair length or cut the hair of Black women as a punishment. Cutting her hair, then, was an opportunity for Rose to reassert her own sense of belonging, not to a slaveholder, but to her daughter. Denied most physical possessions, her hair was one of the few things Rose truly owned. And so she gave it to Ashley, hoping her daughter would remember her by it. Ruth’s words prove that this braid worked just as intended.

In addition to her material analysis, Miles also uses more traditional archival sources. To characterize Rose, Ashley, and Ruth’s emotional lives, she extrapolates from the few written accounts of contemporary figures with similar positionalities like Eliza Potter and Harriet Jacobs. Meanwhile, she fills in some of the more concrete details of Rose and Ashley’s lives by delicately interrogating the records of enslavers. Miles tells us that Rose and Ashley lived at Milberry Place Plantation, the country estate of a planter named Robert Martin, who spent most of his time in Charleston. However, when she searched for a Rose who was enslaved in South Carolina in the 1850s, Miles discovered a whole “garden of captured roses.”7 One was listed as “a nurse for the children.”8 Another appeared as a child amidst a family of nature names. In this archive, our Rose had a single distinguishing feature: She loved a little girl named Ashley. That narrowed the search a bit. Miles writes that “While Rose is a recurring name among enslaved women and girls in South Carolina, Ashley is a rarity.”9 Unfortunately, though her name may have been rare, we know that there were in fact countless other Ashleys just as there must have been many other Roses by other names. Communicated through their sack, Rose and Ashley’s grief and love help us to imagine the emotions of countless other mothers and daughters separated by slavery, just as the written accounts of Potter and Jacobs have helped us to better imagine Rose herself.

Miles begins All That She Carried with the suggestion that the lives of enslaved Black women like Rose can help us to navigate the existential threat of climate change. This framing device appears odd at first. What does slavery have in common with our current ecological crisis? Well, in a word, pain. The world seems dark, like there’s no fixing it. We worry for our children, for their future. We wonder if they’ll even have a future. It’s a point that bears repeating: it hurts to be a mother.

In the essay on process that appends her book, Miles quotes David Glassberg on climate change declension narratives: “Parables of resilience have the most value for public historians since properly told they neither romanticize the past nor imply that it’s too late to avoid a pre-determined dystopian future.”10 In March of this year, the UN released a climate change report claiming that the climate crisis has caused “irreversible damage.”11 In fact, the word irreversible appeared in the document ten separate times as if to say no, really, there’s no coming back from this. And yet, we are not doomed. In the wake of its release, IPCC Chair Hoesung Lee told reporters, “This report offers hope and it provides a warning.”12 Tragedy makes us passive. If there’s no hope, why bother? But if we take action to change our course, we can survive irreversible damage. We’ll make hard choices, and beautiful memories will come to exist alongside the ugly ones.

Too often, stories like Rose’s are confined to pain. This makes them hurt to remember and hurt to retell. But Ashley kept her mother’s story. She passed it down to her daughter and to her daughter’s daughter, who wrote it down for everyone to see. Perhaps, for Ruth, it was a story that both offered hope and provided a warning. In the face of an existential threat, Rose did what she could. Her story was not defined by pain, though it had pain in it. Instead, it was filled with love–packed full of it always.

1 Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 54.

2 Tiya Miles, All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake (New York: Random House, 2021), 295.

3 Tiya Miles, All That She Carried, 5.

4 Tiya Miles, All That She Carried, 298.

5 Tiya Miles, All That She Carried, 212.

6 Tiya Miles, All That She Carried, 133.

7 Tiya Miles, All That She Carried, 62.

8 Tiya Miles, All That She Carried, 63.

9 Tiya Miles, All That She Carried, 67.

10 Tiya Miles, All That She Carried, 295.

11 “Summary for Policymakers,” in Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III tothe Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, ed. The Core Writing Team, Hoesung Lee, and José Romero (Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC, 2023), 1-34.

12 Sarah Kaplan, “World is on brink of catastrophic warming, U.N. climate change report says,” The Washington Post, March 20, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2023/03/20/climate-change-ipcc-report-15/.

Leave a Reply