Retail Encyclopedias: The Materials and Making of Sears Roebuck Catalogs

By Naomi Subotnick, ’22

When Richard Warren Sears and Alvah Curtis Roebuck founded their mail order company in 1886, they were responding to major changes in transportation and communication technologies.1 An expanding rail system was increasingly connecting the country, allowing retail items to be shipped to once-remote rural areas. The introduction of Rural Free Delivery in 1896 meant that rural Americans could now have goods shipped directly to their homes. Sears, Roebuck & Co. grew rapidly, offering a wide selection of goods at standardized prices. The selection of merchandise was comprehensive: the 1897 catalog listed everything from general hardware and cutlery to groceries and musical instruments.2 Indeed, between 1908 and 1940, Sears even sold kit houses. By 1916, Sears was mailing more than 50 million catalogs yearly. 3

As objects, mail order catalogs have generally been considered to be a type of trade catalog. Several scholars have documented the history of trade catalogs in the United States: Lawrence B. Romaine’s Guide to American Trade Catalogs, 1744–1900 represents the foundational bibliography on the subject, and Theodore R. Crom has written about both European and American trade catalogs, dating the development of the form to the eighteenth century.4 The more detailed studies of mail order catalogs tend to consider their social function over their form, positioning them as primary sources for histories of nineteenth-century American consumer culture. However, mail order catalogs represent a distinct category of book: the particular circumstances of their development dictated the ways in which they were designed and printed.

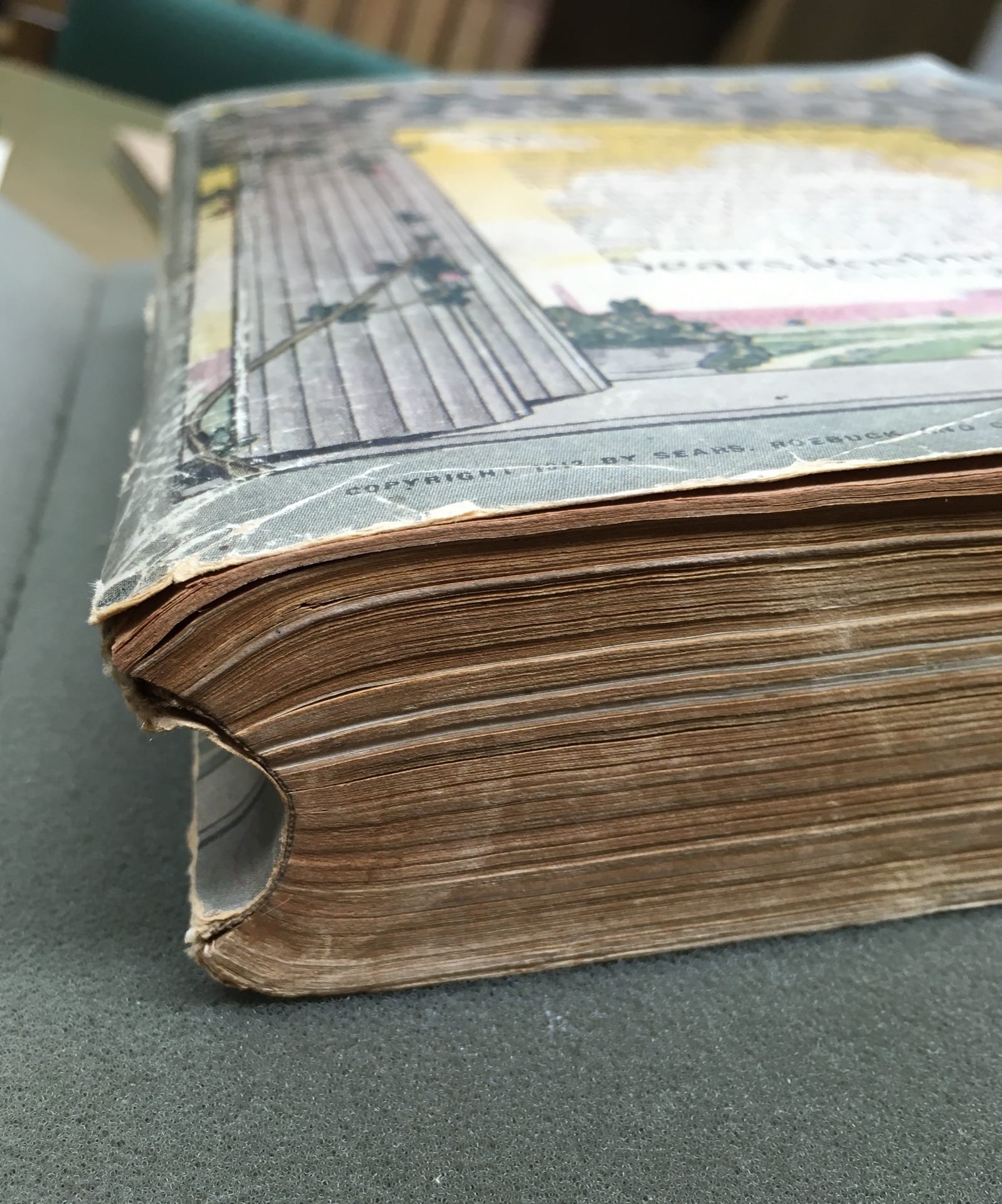

The adhesive binding and newsprint-like pages of a 1912 catalog from Sears, Roebuck & Co. were chosen as materials because the book had to be easily mailable: the soft binding and lightweight paper reduced shipping costs, allowing for the inclusion of more detailed information about the company’s merchandise.

Sears, Roebuck and Company. Catalog No. 124. Chicago: Sears, Roebuck and Company, 1912. Winterthur Library. Photograph by author.

Sears, Roebuck and Company. Catalog No. 124. Chicago: Sears, Roebuck and Company, 1912. Winterthur Library. Photograph by author.

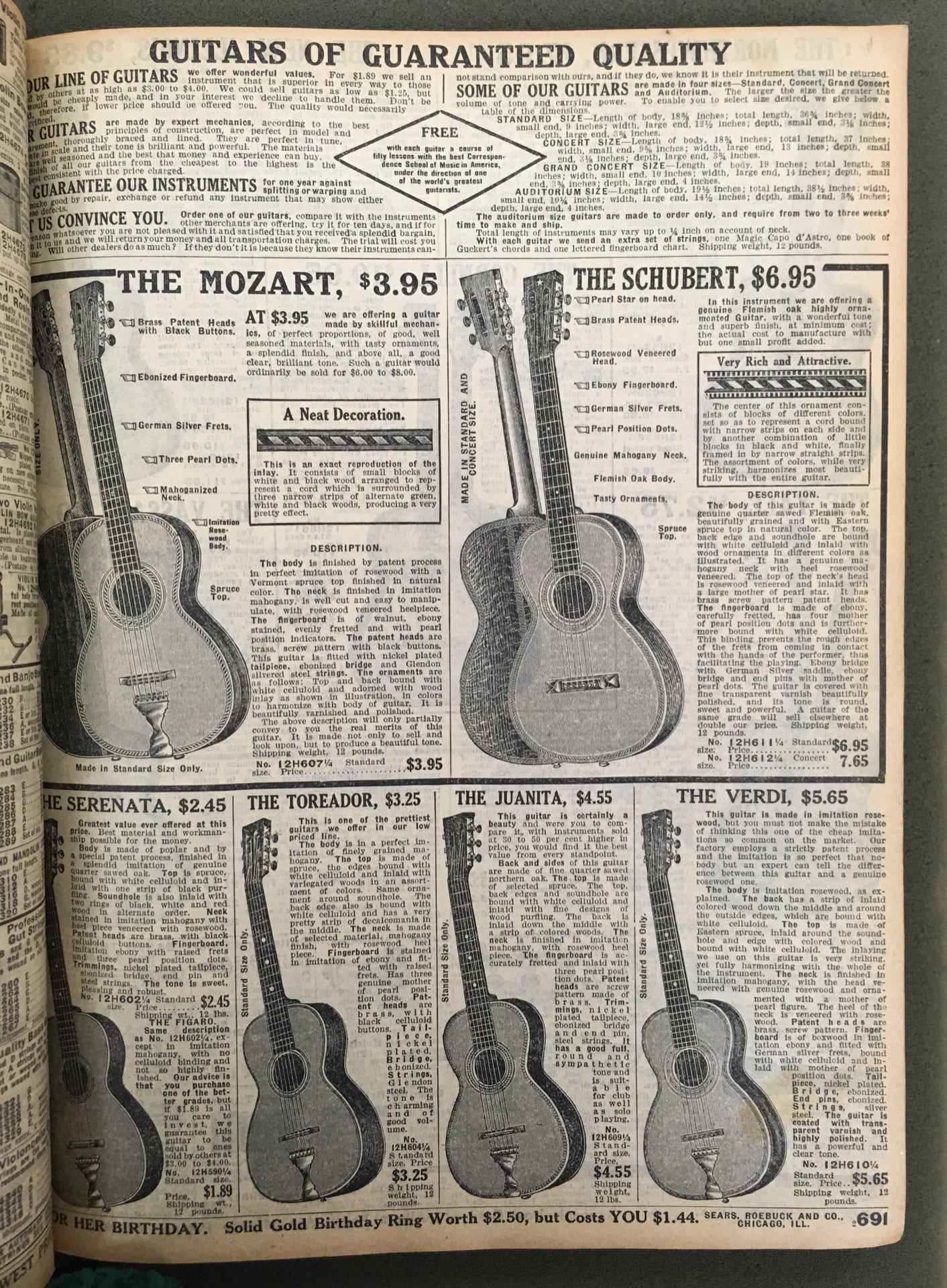

Because the items sold by Sears were purchased by consumers remotely, visual depictions needed to be as accurate as possible. As Richard Rovere notes, “one had to take it on faith that Sears Roebuck & Co. was more than a fiction. The pictures of the warehouses, the plausible addresses in large print and the testimonials of the bankers helped, but they did not establish the materiality, to say nothing of the reliability, of the merchants.”5 In order to faithfully represent products and to build consumer trust, catalog images were engraved directly from photographs of the objects. The 1897 catalog assuaged the doubtful consumer: “Our illustrations and descriptions,” the catalog declared, “are such as will enable you to order intelligently; in fact, so that you can tell what you are getting as well as if you were in our store selecting the goods from stock.”6 A catalog entry for “Guitars of Guaranteed Quality” provides a detailed description of the item, even including a reproduction of the decorative inlay.

Sears, Roebuck and Company. Catalog No. 124. Chicago: Sears, Roebuck and Company, 1912. Winterthur Library. Photograph by author.

Sears, Roebuck and Company. Catalog No. 124. Chicago: Sears, Roebuck and Company, 1912. Winterthur Library. Photograph by author.

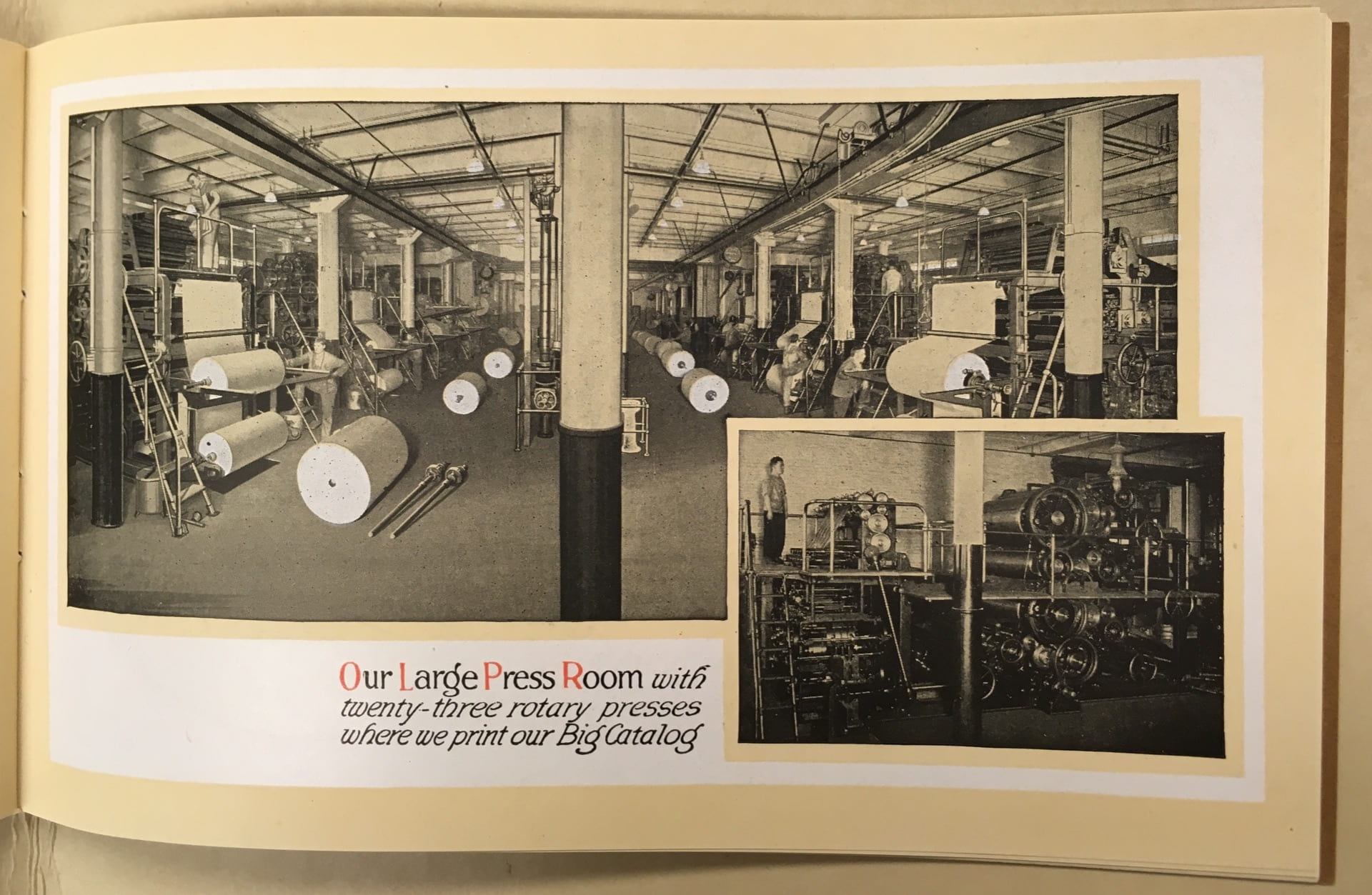

The sheer volume of catalogs printed by Sears meant that production had to be as efficient and streamlined as possible. A promotional pamphlet issued by the company in 1916, titled A Visit to Sears, Roebuck and Co., gives some sense of the printing process. The pamphlet aimed not only to make transparent the shipping process but also to convince the consumer of its revolutionary efficiency and scope. Here one could see pictures of the mail opening department, the correspondence department, and the grocery stockrooms, all populated by uniformed employees.7 “No sooner is one edition ready for the presses than copy is being prepared for the next edition,” proclaimed the pamphlet.8 Catalog production was centralized in one building: after being formatted on a Linotype machine, the type forms were then sent to an electrotype foundry, and printed on rotary presses. Four-color process printing presses were used to create color images. The printed sections were then bound and covered before being mailed directly to consumers.9 “To get an idea of the tremendous output of the Printing Building,” the pamphlet proudly explained, “the yearly product in Big Catalogs alone, if the catalogs were placed end to end, would stretch 1,000 miles; or if placed one on top of the other, they would make a pile more than 150 miles high.”10

Sears, Roebuck and Company. A Visit to Sears, Roebuck and Co. Chicago: Sears, Roebuck and Company, 1916. Winterthur Library. Photograph by author.

Sears, Roebuck and Company. A Visit to Sears, Roebuck and Co. Chicago: Sears, Roebuck and Company, 1916. Winterthur Library. Photograph by author.

Sears, Roebuck and Company. A Visit to Sears, Roebuck and Co. Chicago: Sears, Roebuck and Company, 1916. Winterthur Library. Photograph by author.

The Sears catalogs functioned as retail encyclopedias, but they were also advertisements. A great deal of attention was paid to making objects look attractive to the consumer: image and text were appealingly coordinated. In an advertisement for “The Piccadilly” suit from the 1912 catalog, a man steps deftly across the page towards the viewer, confidently crossing the printed red border around him. A page from the same catalog advertising “Veils and Motor Scarves” depicts not only the items being sold, but also gives some suggestions about how to style the garments.

Sears, Roebuck and Company. Catalog No. 124. Chicago: Sears, Roebuck and Company, 1912. Winterthur Library. Photograph by author.

Sears, Roebuck and Company. Catalog No. 124. Chicago: Sears, Roebuck and Company, 1912. Winterthur Library. Photograph by author.

Sears was not only selling goods, but an entire consumer experience. With its beautifully rendered images and exciting descriptions, leafing through the catalog was enjoyable. More importantly, it reminded readers that they had immediate access to an endless variety of retail goods. Contained within the pages of the Sears, Roebuck & Co. mail order catalogs was the promise of material availability, an aspirational consumer lifestyle, and an accompanying faith in the technologies that made it possible.

References:

Sears, Roebuck and Company. Catalog No. 124. Chicago: Sears, Roebuck and Company, 1912. Winterthur Library.

Sears, Roebuck and Company. A Visit to Sears, Roebuck and Co. Chicago: Sears, Roebuck and Company, 1916. Winterthur Library.

Crom, Theodore R. Trade Catalogues 1542 to 1842. Florida: Storter Printing Company, 1989.

Emmet, Boris and John E. Jeuck. Catalogues and Counters: A History of Sears, Roebuck and Company. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1950.

Graydon, Samuel. Some Notes on Catalog Making. New York: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., 1921.

McKinstry, E. Richard. Trade Catalogues at Winterthur: A Guide to the Literature of Merchandising, 1750–1980. New York: Garland Publishing, 1984.

Romaine, Lawrence B. A Guide to American Trade Catalogs, 1744–1900. New York: Dover, 1990.

Sears, Roebuck and Company. 1897 Sears Roebuck Catalogue. Introductions by S.J. Perelman and Richard Rovere, ed. Fred L. Israel. Reprint, New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1968.

- Boris Emmet and John E. Jeuck, Catalogues and Counters: A History of Sears, Roebuck and Company (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1950), 26. ↩

- Sears, Roebuck and Company, 1897 Sears Roebuck Catalogue, with introductions by S.J. Perelman and Richard Rovere, ed. Fred L. Israel, (Reprint: New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1968), vii. ↩

- Sears, Roebuck and Company, A Visit to Sears, Roebuck and Co. (Chicago: Sears, Roebuck and Company, 1916). ↩

- Theodore R. Crom, Trade Catalogues, 1542 to 1842 (Florida: Storter Printing Company, 1989), 5. Most scholars identify the first example of an American trade catalog to be Benjamin Franklin’s 1744 illustrated pamphlet advertising his new stove. However, according to Romaine, this was likely not the only American trade catalog produced before 1750, but rather the only one that has been preserved. Prior to around 1830, Crom notes that trade catalogs were not widely used in the United States, although he does identify some catalogs advertising drugs and scientific instruments: Romaine also identifies booksellers as early users of the catalog format. ↩

- Richard Rovere, “A Mirrored Image,” introduction to 1897 Sears Roebuck Catalogue, Sears, Roebuck and Company (Reprint: New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1968), xvii. ↩

- Sears, Roebuck and Company, 1897 Sears Roebuck Catalogue 1897 (Reprint: New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1968), 1. ↩

- Sears, Roebuck and Company, A Visit to Sears, Roebuck and Co., 1916 ↩

- A Visit to Sears, Roebuck and Co. ↩

- A Visit to Sears, Roebuck and Co. explains that trimmings from from the catalogs “amount to 2,200 tons a year and they are conveyed from the machines by blowers which shoot them into a packing plant on the railroad side of the building, where they are baled by machinery and sold as a by-product.” It would be interesting to explore whether there were other byproducts of the printing process, and if so, how they may have been used. ↩

- A Visit to Sears, Roebuck and Co. ↩

Can you tell me how much a Sears catalog from 1902 and in excellent condition is worth?