Misidentified for Nearly One Hundred Years: The History of a Maine-Made Chest of Drawers in the Winterthur Museum

By Catherine Cyr, ’22

In September 1928, Henry Francis du Pont wrote to furniture dealer Isaac Sack indicating his desire to purchase a “Satinwood and mahogany chest of drawers with five oval satinwood panels.”1 Not long after acquiring the chest of drawers from Sack, du Pont loaned the item to the 1929 “Girl Scout Loan Exhibition” in New York City.2 The exhibition aimed to showcase extraordinary examples of American-made furniture in private collections. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., Louis Guerineau Myers, and Henry Francis du Pont were just a few of notable collectors involved in the exhibition. After making its grand public appearance at the blockbuster exhibition, the chest of drawers eventually made its way to du Pont’s home, the future Winterthur Museum. It was placed in the Albany Room, and would be in the public eye once more when the museum opened a few decades later. While this chest of drawers has been a fixture in the Albany Room for many years, it has only been within the last twenty that the object has been properly identified as a product of the Cumston and Buckminster workshop, representing one of the finest examples of Maine-made furniture in the Winterthur collection.

Bow Front Chest of Drawers (ca. 1809-1816), attributed to Cumston and Buckminster Workshop, Saco, Maine (Winterthur Museum, 1957.0564). Photograph by author.

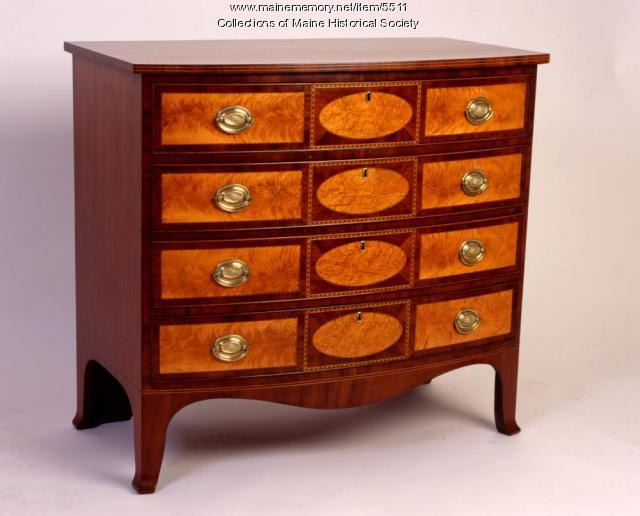

H. F. du Pont’s initial description of the chest of drawers is misleading: the bow front chest of drawers, dating between 1809 and 1816, contains no satinwood in its construction or decoration. Rather, the case is constructed of white pine, and the curved drawer fronts and attached apron are exquisitely decorated with mahogany and flame birch veneer panels. Six different stringing designs, all exhibiting geometric patterns of alternating light and dark wood, are used to outline the veneered panels. Each drawer is finished with two stamped brass handles and decorative backplates attributed to the Hands & Jenkins firm of Birmingham, England.3 Due to this distinctive construction and design, the chest of drawers was assumed to be Portsmouth-made for much of the twentieth century. It was not until a 2001 article published in The Magazine Antiques by Thomas Hardiman, Jr. that the true history of this object was revealed: it was made in Saco, Maine, about forty miles north of Portsmouth, by Joshua Moody Cumston and David Buckminster.

Detail of top drawer (featuring Hand and Jenkins stamped brass hardware), Bow Front Chest of Drawers (ca. 1809-1816), attributed to Cumston and Buckminster Workshop, Saco, Maine (Winterthur Museum, 1957.0564).

It is no coincidence that the Cumston and Buckminster chest of drawers bears resemblance to contemporary Portsmouth-made examples. Joshua Moody Cumston (1784-1835) was most likely apprenticed under his cousin Joseph Clark (1761-1851), who operated a cabinetmaking shop in Portsmouth around the turn of the nineteenth century.4 It was in Clark’s shop that Cumston would have learned to replicate the construction and decoration of bow front chests of drawers in the Portsmouth style. Cumston eventually returned to his native Saco after his apprenticeship, bringing his new skills with him, and established a shop in 1808, hiring David Buckminster (1786-1849) as a journeyman one year later.5 Born in Framingham, Massachusetts, it is assumed that Buckminster relocated to Saco around 1809, as his brother had moved to the area a few years prior.6 Little is known about Buckminster’s training: Hardiman suspects that he may have been apprenticed in a cabinetmaking shop in Worcester County before moving to Saco, but no known documentation supports this assertion. In 1811, the two men officially became partners and the Cumston and Buckminster shop was born.

Detail of top drawer center, showing the mahogany and flame birch veneered panel, Bow Front Chest of Drawers (ca. 1809-1816), attributed to Cumston and Buckminster Workshop, Saco, Maine (Winterthur Museum, 1957.0564).

No advertisements for the Cumston and Buckminster shop appear to have survived, and histories of the City of Saco have generally neglected to mention their work. Their absence from local papers and later histories is odd, as they appear to have maintained consistent commercial success: the shop employed at least seven men by 1815, and Cumston was known to have trained multiple apprentices.7 It is possible that the shop was sustained by a steady stream of commissions, which would have kept multiple workers busy and limited the need for advertisements. Cumston certainly had strong familial ties to wealthy Saco families, including the Pepperell family. On May 14, 1816, an advertisement in The Portland Gazette informed the public that Cumston and Buckminster’s partnership would officially dissolve, and one month later Cumston sold the shop and property to Buckminster.8. Deed. Joshua M Cumston to David Buckminster, June 15, 1816. Saco, Maine.] Buckminster led the shop for many years, and after his death in 1849 the business remained open under the guidance of Abraham Forsskol, a Swedish immigrant who joined the shop in 1814 as a journeyman and was later promoted to partner by Buckminster.

Detail of apron and skirting, Bow Front Chest of Drawers (ca. 1809-1816), attributed to Cumston and Buckminster Workshop, Saco, Maine (Winterthur Museum, 1957.0564).

Today, a small group of objects, including chests of drawers, sideboards, and tables, have been attributed to the Cumston and Buckminster shop. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many have been misidentified as Portsmouth-made furniture. Cumston and Buckminster’s most noteworthy furniture form appears to be the bow front chest of drawers with oval flame birch veneer panels. These chests of drawers differ from those made by Portsmouth cabinetmakers during the period in three distinct ways: the French feet lack spurs, the stringing on the skirt warps around the sides and bottom of the oval panels rather than traveling straight across the bottom of the chest, and the drawers appear to exclusively feature Hand and Jenkins brass hardware.

Winterthur’s Cumston and Buckminster chest of drawers points to the high level of craftsmanship present in the District of Maine in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, and to the presence of fashionable neoclassical furniture outside major city centers. Saco, and southern Maine more generally, was a place of wealth and influence during the period: homes built in Saco rivaled those of Portsmouth and Salem.9 The stylish furniture that was readily available in those larger shipping ports was also needed to fill the grand homes of southern Maine. Indeed, multiple Cumston and Buckminster chests of drawers have established provenances from prominent families in the area. Winterthur’s chest of drawers is believed to have connections to the Wingate family of North Hampton, New Hampshire, who have noted ties to Saco resident Dr. Thomas G. Thornton, a U.S. Marshal for the District of Maine during the War of 1812.10 Thanks to Cumston and Buckminster’s training and knowledge of period tastes, the shop was able to deliver outstanding craftsmanship and design to their Maine clients, mirroring and possibly exceeding the quality of products produced by their New Hampshire and Massachusetts counterparts.

Bow Front Chest of Drawers (ca. 1809-1816), attributed to Cumston and Buckminster Workshop, Saco, Maine. Collection of Maine Historical Society, Wadsworth-Longfellow House. Image courtesy of Maine Memory Network and Maine Historical Society. https://www.mainememory.net/artifact/5511.

The chests of drawers made at the Cumston and Buckminster shop are works of art. However, scholars, collectors, and even visitors to the Winterthur Museum remained unaware of Maine’s flourishing cabinetmaking tradition for much of the twentieth century. There may yet be misidentified Maine-made furniture in collections across the country. It will take the work of local scholars like Hardiman, curators, and furniture historians to better understand, identify, and share the history of Maine cabinetmakers. It is this author’s hope that any future blockbuster exhibitions highlighting the history and craftsmanship of American-made furniture will rightfully include pieces from early Maine cabinetmakers, preserving and celebrating their important achievements.

- Henry F. du Pont, Henry F. du Pont to Israel Sack, Southampton, Long Island, New York, September 5, 1928. ↩

- For more information about the ‘Girl Scout Loan Exhibition,’ see Wendy Cooper, “A Historic Event: The 1929 ‘Girl Scout Loan Exhibition,’” The American Art Journal 12, no. 1 (Winter 1980): 28-40. ↩

- Donald L. Fennimore and George J. Fistrovich, Metalwork in Early America: Copper and Its Alloys from the Winterthur Collection (Winterthur: Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 1996), 441. See catalog no. 312. ↩

- For more information about Joseph Clark, visit the Joseph Clark (1761-1851) Biographical Entry in the New Hampshire Historical Society Online Collection Database, https://www.nhhistory.org/object/1222315/clark-joseph-1767-1851. ↩

- Thomas Hardiman, Jr. “Veneered Furniture of Cumston and Buckminster, Saco, Maine,” Magazine Antiques, May 2001, 757. ↩

- “Births, Marriages, Deaths: Volume II, 1708-1808, Town of Framingham.” Massachusetts Vital and Town Records. Courtesy of Ancestry. (Accessed April 7, 2021). ↩

- Hardiman, “Veneered Furniture of Cumston and Buckminster, Saco, Maine,” 757. ↩

- “Advertisement,” Gazette (Portland, Maine) XIX, no. 8, May 14, 1816: [3 ↩

- Hardiman, “Veneered Furniture of Cumston and Buckminster, Saco, Maine,” 758. ↩

- Hardiman, “Veneered Furniture of Cumston and Buckminster, Saco, Maine,” 756. ↩

Leave a Reply