“A Mass of Barbarous Splendour”: A Papier-Mâché Writing Desk in the Winterthur Collection

By Jena Gilbert-Merrill, ’22

This ladies’ writing desk, a recent and somewhat anomalous acquisition to Winterthur’s collection, presents us with a unique materiality, extravagant ornamentation, and an intriguing multipurpose function. This object combines a writing desk, a game table, a sewing box, and a vanity. The desk also comes apart, transforming so that the user may access the different functions contained within.1

On a black japanned background, a mélange of hand-painted Rococo swirls and swags embellish mother-of-pearl details, surrounded by geometric borders that are vaguely classical in design. The top portion of the desk contains the writing surface, a small cabinet with four drawers, and a mirror at the very top. The front of the desk depicts Osborne House, Queen Victoria’s beloved country estate to which she retired upon the death of her husband, Prince Albert. This front face folds out to reveal a bright blue, velvet-lined writing surface embossed with floral decoration.

The top portion of the desk can be removed, revealing a chess board whose checkered surface is delineated with gilt lines and mother-of-pearl decoration. Inside the table is a drawer divided into several compartments lined with blue moiré silk and embossed paper. The drawer contains a thimble and ornamented bobbins, and several of the compartments have removable lids also lined in silk and paper. The desk stands on scrolled legs which lock together to form the elegant shape of a lyre, embellished with colorful painted detail, iridescent swathes of pearl, and meticulously stenciled gilding.

Ladies’ Writing Desk. Jennens & Bettridge, ca. 1847-1864. Papier-mâché, mother of pearl, paint, gilt, varnish. Winterthur Museum, 2020.0018 A-C. Image by author.

This desk was likely made between 1847 and 1864 by the Birmingham firm Jennens & Bettridge, a company which specialized in papier-mâché furnishings. The glittering, almost garish decoration on this desk is eye-catching, but it was the materiality of this object that truly captured my attention. The use of papier-mâché in the construction of this desk helps to situate this object within the history of British design.

Papier-mâché was used in Britain as early as 1672, but a number of technological and material developments over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries allowed for it to be used in new and innovative ways. Throughout its history, papier-mâché was used as a cheaper alternative to carved wood: first in architectural ornament and decorative frames, then in lieu of carved elements on chairs, and finally as a building material itself. The techniques used to cast papier-mâché allowed for more complex designs than a wood or plaster carver could reasonably expect for the same cost, and its ease of use created an interest in expanding the functions of this material.2

By the mid-eighteenth century, interest in papier-mâché was spreading throughout Europe and the material became somewhat fraught for the political implications it carried. In England specifically, papier-mâché became something of an outlet for Francophobic sentiment. Thomas Johnson, a prominent eighteenth-century English wood carver, produced a design which “incorporated a cherub setting fire to a scroll inscribed ‘French Paper Machee.”3 However, despite this patriotic commitment to the traditional material of wood, papier-mâché slowly took hold in England between the 1750s-60s, and the material was eventually claimed as a uniquely British innovation. During this period, papier-mâché was used for small domestic objects such as frames, trays, and boxes, and as an alternative for decorative and architectural woodwork, with designers as prominent as Thomas Chippendale incorporating it in small quantities. The late eighteenth-century saw further technical improvements in the manufacture of papier-mâché: Henry Clay patented a technique for pressing up to ten sheets of heat-resistant paper panels into metal molds, using a binding agent and linseed oil before drying the composite in a kiln to create a hard, strong material that could be carved and worked like wood.4

Within the first half of the nineteenth century, Jennens and Bettridge had taken over Clay’s factory, expanding upon these earlier innovations to patent two techniques that allowed them to mass produce larger, more extravagant pieces of papier-mâché furniture. With their use of steam-powered press molding and an efficient new technique for mother-of-pearl and gem inlay, Jennens and Bettridge established themselves as the premier manufactory of papier-mâché furnishings in Europe.

Balloon back chair. Jennens & Bettridge, ca. 1850. Japanned and painted wood, papier-mâché, mother-of-pearl, replacement upholstery. Victoria & Albert Museum, W.3B/1,2-1929. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O80330/chair-jennens-and-bettridge/.

In 1847, Theodore Hyla Jennens secured a patent for a steam-molding technique in which 120 sheets of paper were pressed into metal molds, heated, and dried. This development allowed for papier-mâché to be cast in large quantities into pre-shaped molds, rather than built up from individual layers of paper. The decorative “inlay” technique used by Jennens and Bettridge’s was not truly inlay, as the pearls and gems added to an object were actually very thin pieces affixed to the surface with layers of varnish, rather than embedded within it.5 The result of these two processes was a strong, moldable material that could be easily cast into any number of shapes, assembled from its pre-fabricated parts, and decorated in such a way that appeared much more technical than it really was.

Detail of decoration on a bottom rail of Winterthur’s papier-mâché writing desk. Jennens & Bettridge’s decoration technique is visible here: the mother-of pearl that makes up the center of the floral design is treated as a ground, and paint is applied as embellishment on the top. Some of the paint has worn away, revealing the iridescent surface underneath. Image by author.

Charles Frederick Bielefeld, an early nineteenth-century innovator in the material of papier-mâché, extolled the modernity of this process, boasting in an 1842 treatise of the material’s strength, flexibility, and technical mystery.6 The concept of a modern technical process that resulted in the new quality of plasticity was surprisingly controversial. With form no longer restrained by limitations of material, craftsmanship, or human labor, the tastefulness of these new consumer goods was called into question. Papier-mâché, with its plastic, moldable properties and potential for mass production, sparked disagreement over the role of human intervention in material aesthetics.

Jennens and Bettridge won accolades at the 1851 Great Exhibition for their material and technical innovations.[7. Jennens & Bettridge’s Illustrated Catalog of Papier-Mâché, 1851-1852, (London: Peter, Duff, and Co., 1851-1852). Available at: https://archive.org/details/jennensbettridge00jenn/mode/2up] The new, mysterious, plastic quality of papier-mâché (qualities also evident in cast iron and vulcanized rubber), were taken by some as evidence of Britain’s industrial might and national superiority. Others expressed anxiety at the new material: early design reformers like A.W.N. Pugin denounced “the mechanical contrivances and inventions of the day, such as…papier-mâché, and a host of other deceptions,” which “only serve to degrade design, by abolishing a variety of ornament and ideas, as well as the boldness of execution, so admirable and beautiful in ancient carved works.”7 Landscape architect Humphry Repton noted, “the cheapness and facility with which good designs may be multiplied in papier maché…have encouraged bad taste in the lavish profusion of tawdry embellishment.”8 For its critics, the absence of visible handwork seemed a disastrous threat to the humanity in craftwork and design, which had historically presented itself through detailed embellishment that was impressive and valuable precisely for the amount of labor it implied.

Pages 4 and 5 of Jennens & Bettridge Illustrated Catalogue of Papier Mâché, ca. 1851-52. London: Peter, Duff, and Co., 1851-1852. Winterthur Library, NA3680 J54 TC. The entire catalog has been digitized and is available here: https://archive.org/details/jennensbettridge00jenn/mode/2up.

This desk tells a story not only of nineteenth-century industry and technology in Britain, but of the shifting aesthetic ideals that would come to shape the Arts and Crafts movement. This object may be situated within a liminal moment in the history of British design– at the cusp of industrialization’s crowning achievement and its rejection– embodying British anxieties about industrial materials as both modern innovations and sinister threats to design principles.

This desk represents a moment of change in the perception of craft, materiality, and labor. It also prompts a series of further questions. How would such an object fit into daily life in Victorian Britain? What does the multifunctional dimension of this object say about what nineteenth century British consumers demanded of their furnishings? There is ample evidence of British interest in fancy, convertible, or mechanical furniture in this period, but what would it have been to live with this object at a time when such an item was a novelty?9 Furthermore, how is gender encoded in the functionality and materiality of this ladies’ writing desk, as opposed to desks made for gentlemen?

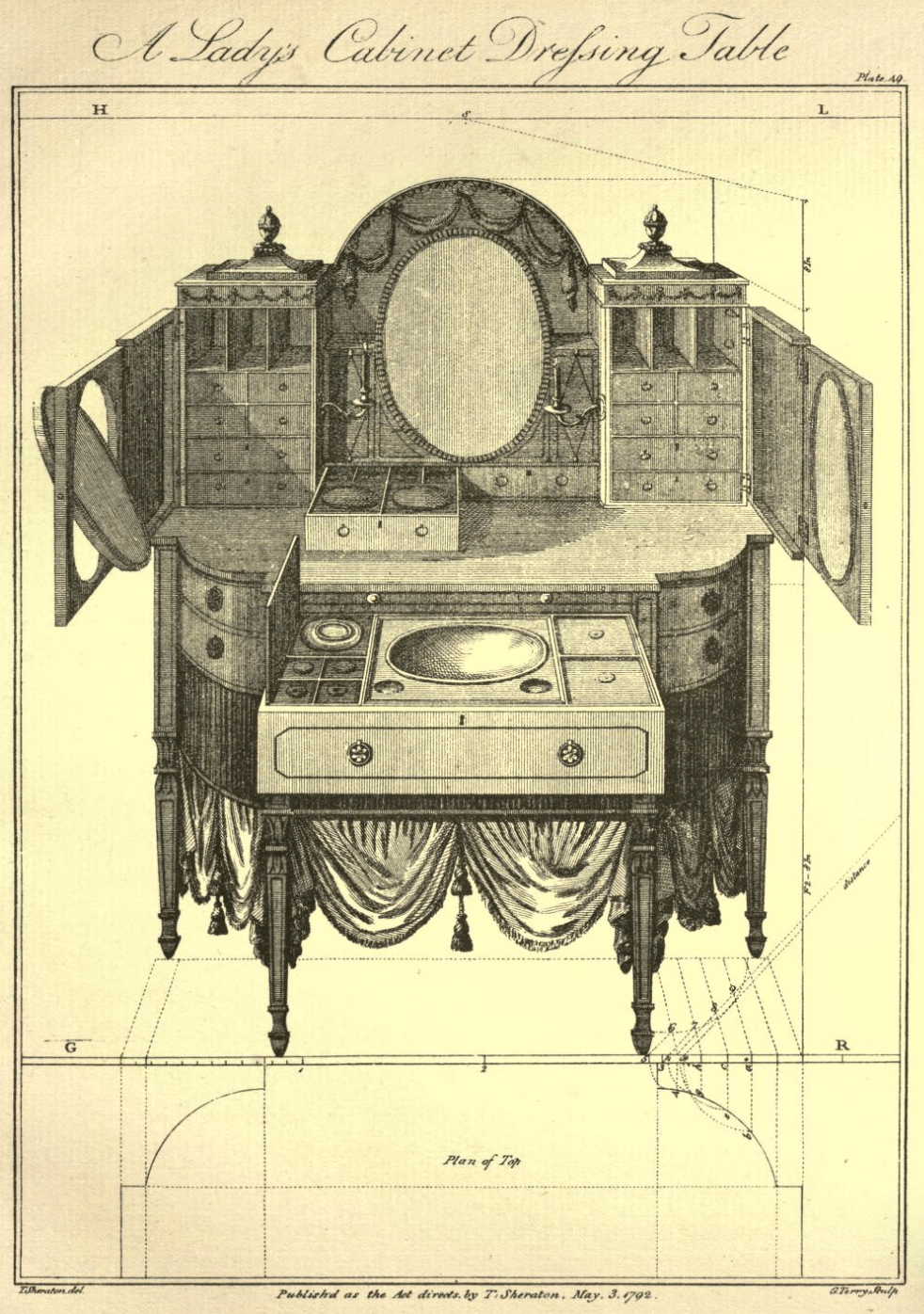

Illustration of “A Ladies’ Cabinet Dressing Table” from Thomas Sheraton’s 1791 The Cabinet-maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book. A number of Sheraton’s designs in this book feature a similarly convertible or mechanical quality, revealing a British interest in novel, multifunctional or fancy furnishings that provide some precedent for the Jennens & Bettridge writing desk. Sheraton’s book is available here: https://archive.org/details/cabinetmakerupho00sheruoft/mode/2up.

Finally, while this object falls outside of the purview of what Winterthur typically collects (the desk is English, and nineteenth-century), it exemplifies some major themes that shape Winterthur’s collection more broadly, such as fancy painted furniture and objects decorated with national symbols. In this respect, an object so steeped in British design history as this ladies’ writing desk can illuminate new facets of American material culture.

- The painter Richard Redgrave described this kind of papier-mâché furniture as, “a mass of barbarous splendour that offends the eye and quarrels with every other kind of manufacture with which it comes in contact.” Quoted in John Morley, The History of Furniture: Twenty-Five Centuries of Style and Design in the Western Tradition (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1999), 252. ↩

- Diane van der Reyden and Don Williams, “The History, Technology, and Care of Papier-Mache: Case Study of the Conservation Treatment of a Victorian “Japan Ware” Chair,” Cooper Hewitt Museum, Smithsonian Institution; Pat Kirkham, “The London Furniture Trade 1700-1870,” in Furniture History, The Furniture History Society, vol. 24, 1988: 117. ↩

- Pat Kirkham, “The London Furniture Trade 1700-1870” in Furniture History, The Furniture History Society, vol. 24, 1988: 118 ↩

- Diane van der Reyden & Don Williams, “The History, Technology, and Care of Papier-Mache: Case Study of the Conservation Treatment of a Victorian “Japan Ware” Chair,” Cooper Hewitt Museum, Smithsonian Institution. ↩

- Van der Reyden & Williams. ↩

- From Charles Frederick Bielefeld, On the Use of the Improved Papier-Mache in Furniture, in the Interior Decorations of Buildings, and in Works of Art (London: J. Rickerby, ca. 1842), 5 cited in Glenn Adamson, The Invention of Craft (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), 83. ↩

- A.W.N. Pugin, Contrasts: A Parallel between the Noble Edifices of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, and Similar Buildings of the Present Day, Shewing the Present Decay of Taste (London: Author, 1836), 35 cited in Glenn Adamson, The Invention of Craft, (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), 87. ↩

- Humphry Repton, Observations on the theory and practice of landscape gardening: including some remarks on Grecian and Gothic architecture, collected from various manuscripts, in the possession of the different noblemen and gentlemen, for whose use they were originally written: the whole tending to establish fixed principles in the respective arts (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), 160. ↩

- A few examples of eighteenth and nineteeth century novelty convertible or mechanical furniture may be found in the following works: Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet-maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book (1791), the “Fashionable Furniture” column in Ackermann’s Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions, and Politics, and patents for convertible furniture such as Stephen Hedges’ 1854 “combined table and chair.” A digitized version of Sheraton’s Cabinet-maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book is available here: https://archive.org/details/cabinetmakerupho00sheruoft/page/n474/mode/thumb. An issue of Ackermann’s Repository with especially relevant “Fashionable Furnishings,” including a globe-shaped writing desk, is available here: https://archive.org/stream/repositoryofarts310acke#page/n7/mode/2up. The patent for Stephen Hedges’ convertible chair, as well as a constructed example of this chair/table are available here: https://patents.google.com/patent/US10740A/en and https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-1316412. ↩

Leave a Reply