The Monarch and the City: Relfe and Fletcher’s 1838 Panorama of Queen Victoria’s Coronation

By Naomi Subotnick, ’22

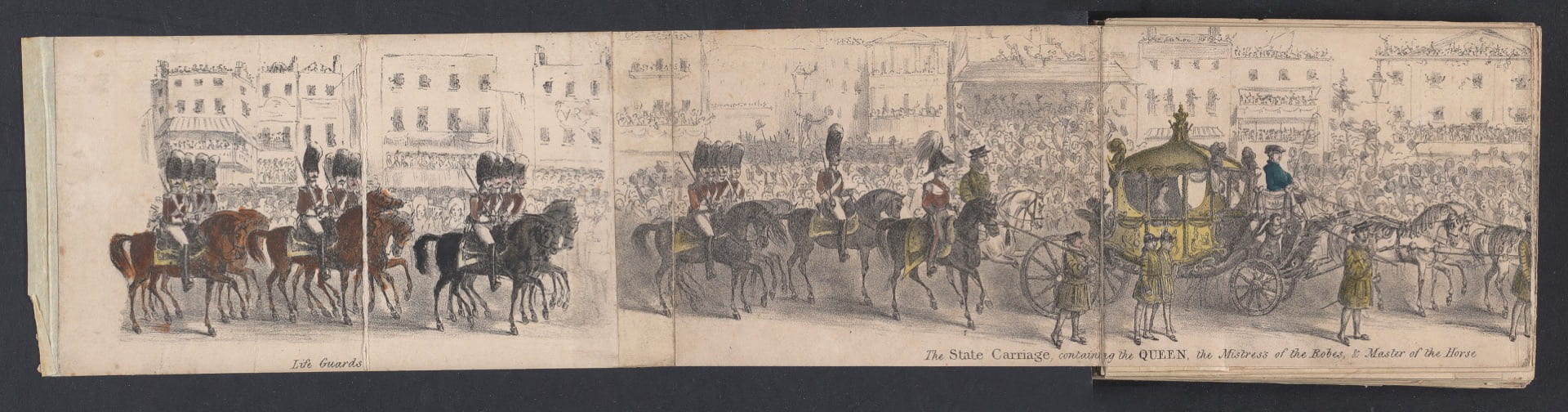

This panoramic view of Queen Victoria’s coronation, published by Relfe and Fletcher in 1838, depicts the royal procession from the Duke of York’s statue to Westminster Abbey. Guards on horseback flank the gilded royal coach, as crowds of eager onlookers stretch namelessly into the distance. Carriage by carriage, the dignitaries traverse London, identified by descriptive text. Scanning the print, the viewer follows the route of the procession through the architectural landscape of London. The coronation blends into the fabric of the city, becoming almost synonymous with London itself.

2020.0017.009.001 A, “The Splendid Procession of Queen Victoria to her Coronation,” Relfe and Fletcher, 1838, hand-colored lithograph, 3.5″ x 128.4″. The print has been framed, but would have originally been distributed as an accordion-folded book.

2020.0017.009.001 A, “The Splendid Procession of Queen Victoria to her Coronation,” Relfe and Fletcher, 1838, hand-colored lithograph, 3.5″ x 128.4″. Small section of the print, depicting Victoria’s royal coach.

Queen Victoria’s coronation, which took place in June of 1838, was designed to be a public spectacle. With a crowd of 400,000 in attendance, the procession advanced from the newly built Buckingham Palace to Westminster, through Hyde Park, Piccadilly, St. James’s Street, Pall Mall, Charing Cross and Whitehall.1 The four-day-long celebration that ensued was meant to awe and entertain, and included a celebratory fair, a hot air balloon ascent, and a fireworks display. Souvenir prints like Relfe and Fletcher’s panorama broadcast the event to an even wider public. This hand-colored lithograph would originally have been distributed as a cloth-bound accordion book (tears now separate the paper where it was once folded), and was perhaps collected as a material reminder of the extravagant ceremony.

From the moment of her coronation, Queen Victoria’s reign was highly publicized in print and visual media. The narrative of her celebrity, which proliferated in newspapers and periodicals, was essential to the construction of Britain’s nineteenth-century imperial identity. The visual technology of the panorama, which combined the Victorian taste for spectacle with a national expression of empire, was a medium perfectly suited to a celebration of the new monarch and the imperial expansion her reign promised.2

Panoramic views of London had first been popularized in 1792 by Robert Barker, whose immersive cityscape filled an entire circular room. As Denise Oleksijczuk has argued, Barker’s panorama “became a crucial cultural site for the emergence of a new public that came to know itself as British through the changing exhibitions of international, global subjects.”3 The popularity of the medium steadily increased through the nineteenth century. According to Bernard Comment, the panorama represented “a double dream come true— one of totality and possession; encyclopedism on the cheap.”4 As Alison Byerly notes, a panorama allowed the viewer to see an entire landscape at once, and so had the effect of “condensing, packaging, and commodifying the travel experience.”5 Large three-hundred-and-sixty degree panoramic exhibitions were popular through the 1870s.6 In smaller print form, panoramas often depicted landscapes, overseas battles, or views of the growing British empire.7 By situating Victoria’s coronation within a panoramic cityscape, Relfe and Fletcher’s print reinforces Queen Victoria’s connection to the physical space of London itself, deepening the growing associations between monarch, city, and empire.

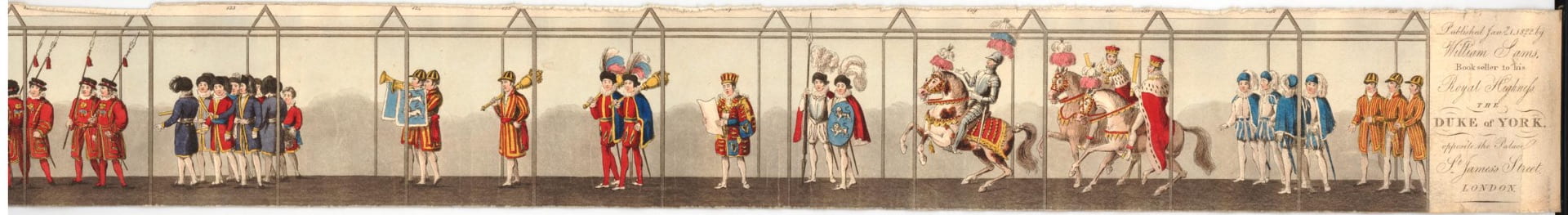

The panoramic form had been used to depict the coronation of British monarchs as early as the seventeenth century. An 1685 engraving from the collection of the British Museum depicts the coronation procession of James II, with earls and dukes proceeding in almost encyclopedic fashion.

James Collins, Nicholas Yeates, and William Sherwin, Order of Procession for Coronation of James II, 1685, engraving, 225mm x 8740mm, The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1871-1209-2467-2483.

An 1822 panorama of George IV’s coronation is similar in composition: the figures move through a geometric space like a series of toy soldiers.

William Sams, Coronation Procession of George IV, 1822, etching and aquatint, The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1890-0808-9.

Yet neither of these coronation panoramas are situated within the city itself: they are meant to showcase for the viewer who was present, rather than where they were. Relfe and Fletcher’s 1838 panorama shows the entire royal procession within the context of the city itself. Neither is this unique among printed images of Victoria’s coronation: several contemporary examples also blend the procession into the landscape of London.

W. Soffe, “Soffe’s Panoramic Representation of the Grand Procession on the Day of the Queen’s Coronation,” 1838, lithograph, Yale Center for British Art, https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/orbis:3471917.

Why would it have been important to meld monarch and city in this way? By associating Queen Victoria’s coronation so closely with the city itself, the print cements London as the center of both nation and empire. The viewer of this print would likely have been familiar with contemporary panoramic views of the city: the queen’s coronation was then superimposed onto an existing visual reference. Unfolding this booklet, the viewer would have encountered Victoria’s image in every consecutive vista of London depicted in the panorama. The print would have prompted viewers to imagine themselves physically present at the coronation, observing the event in real time and space. The buyer of this print would have participated in the coronation over and over again, each time the print was unfolded: more than memorabilia, this was a temporal experience. As the viewer virtually attended the coronation, two symbols of empire– the monarch and the city– were mapped onto each other, crystallizing into a compact, portable vision of British imperialism.

- “Material Relating to the Coronation of Queen Victoria,” British Library, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/material-relating-to-the-coronation-of-queen-victoria. ↩

- John Plunkett has written about the proliferation of print media surrounding Queen Victoria. In particular, see Queen Victoria: First Media Monarch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003). Plunkett’s 2001 article “Of Hype and Type: The Media Making of Queen Victoria 1837–1845” discusses the contemporary discourse in prints, periodicals, and newspapers about the media presence of the queen. See also Bernd Weisbrod, “Theatrical Monarchy: The Making of Victoria, the Modern Family Queen” in The Body of the Queen: Gender and Rule in the Courtly World, 1500–2000 ed. Regina Schulte, Pernille Arenfeldt, Martin Kohlrausch, and Xenia von Tippelskirch (New York: Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2006). Denise Oleksijczuk situates the panorama within discourses of British imperialism in her book The First Panoramas: Visions of British Imperialism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011). Alison Byerly has written extensively about the panorama as a form of virtual travel. ↩

- Denise Oleksijczuk, The First Panoramas: Visions of British Imperialism, 4. ↩

- Bernard Comment, The Painted Panorama (New York: H.N. Abrams, 2000), 19. ↩

- Alison Byerly, “‘A Prodigious Map Beneath His Feet’: Virtual Travel and the Panoramic Perspective,” Nineteenth Century Contexts 29, no. 2-3 (2007): 152. Jonathan Potter makes a similar argument in his 2018 book Discourses of Vision in Nineteenth-Century Britain: Seeing, Thinking, Writing. ↩

- Byerly, “‘A Prodigious Map Beneath His Feet’,” 152-3. ↩

- John Roland Abbey cites numerous examples in his 1953 bibliographic collection Life in England in Aquatint and Lithography, 1770–1860. ↩

I stumbled upon this post by accident and I’m glad I did as it’s such an interesting post, so thank you!

A couple things occurred to me as I read about and looked at these images, and I thought I’d share in case they are useful. First, I really enjoyed your analysis of the presentation of monarchy here. At first impression, it seems to me that these images don’t present an especially equal relationship between monarchy and city. The use of colour and the level of detail seems to weight the importance/attention on those elements relating to monarchy while the city itself fades somewhat into the background (and the crowd, little more than vague shapes, even more so). Compare this to the level of detail that was claimed in Barker’s panoramas, for instance, where viewers were encouraged to pick out details from the background as an affirmation of the “totality” of the image.

My second thought isn’t really point but just something that struck me – the portrayal of London here seems very open to me and made me think, in contrast, of the oppressiveness of the architecture in George Cruikshank’s illustrations for Dickens’ Sketches by Boz – J. Hillis Miller wrote a brilliant essay about.

I was really intrigued by your point about the image as a temporal experience, being used to “participate” in the coronation over and over again. It would be so fascinating if it were possible to follow the life of a panorama like this and gauge changes in how it is viewed and perceived!

Anyway, thanks for writing this post and I’ll be sure to come back and read more from the Material Matters program.