A Familiar Landscape: a Surrogate for Ancestry and Genealogical Legacy?

By Olivia Armandroff, Class of 2020

Created in 1875, Winslow Homer’s wood engraving, The Family Record, depicts new parents adding their infant’s name to such a record, seated beneath what appears to be an ancestral portrait. Capitalizing upon the fascination with genealogy in this time, the genre of family records emerged as blank documents which allowed owners to document their family trees and display their ancestral relationships as marks of pride. Homer’s engraving was made at the same time as the emergence of the Colonial Revival in America, when family ancestry became a means of declaring national belonging, a status celebrated by organizations with exclusive membership such as the Daughters of the American Revolution and the Society of the Cincinnati. But ancestral longevity on the American subcontinent could not only be maintained by descendants of the Puritans. Less easily documented, but equally as enduring, was the African American presence, beginning in 1619 with the arrival of the first slave ship in Jamestown. At the same time as some African Americans were part of a lengthy lineage of American descendants, an absence of written records thwarted their participation in this craze for recording personal ancestry and denied them equal access to the patriotic, nationally-oriented identity that resulted from it.

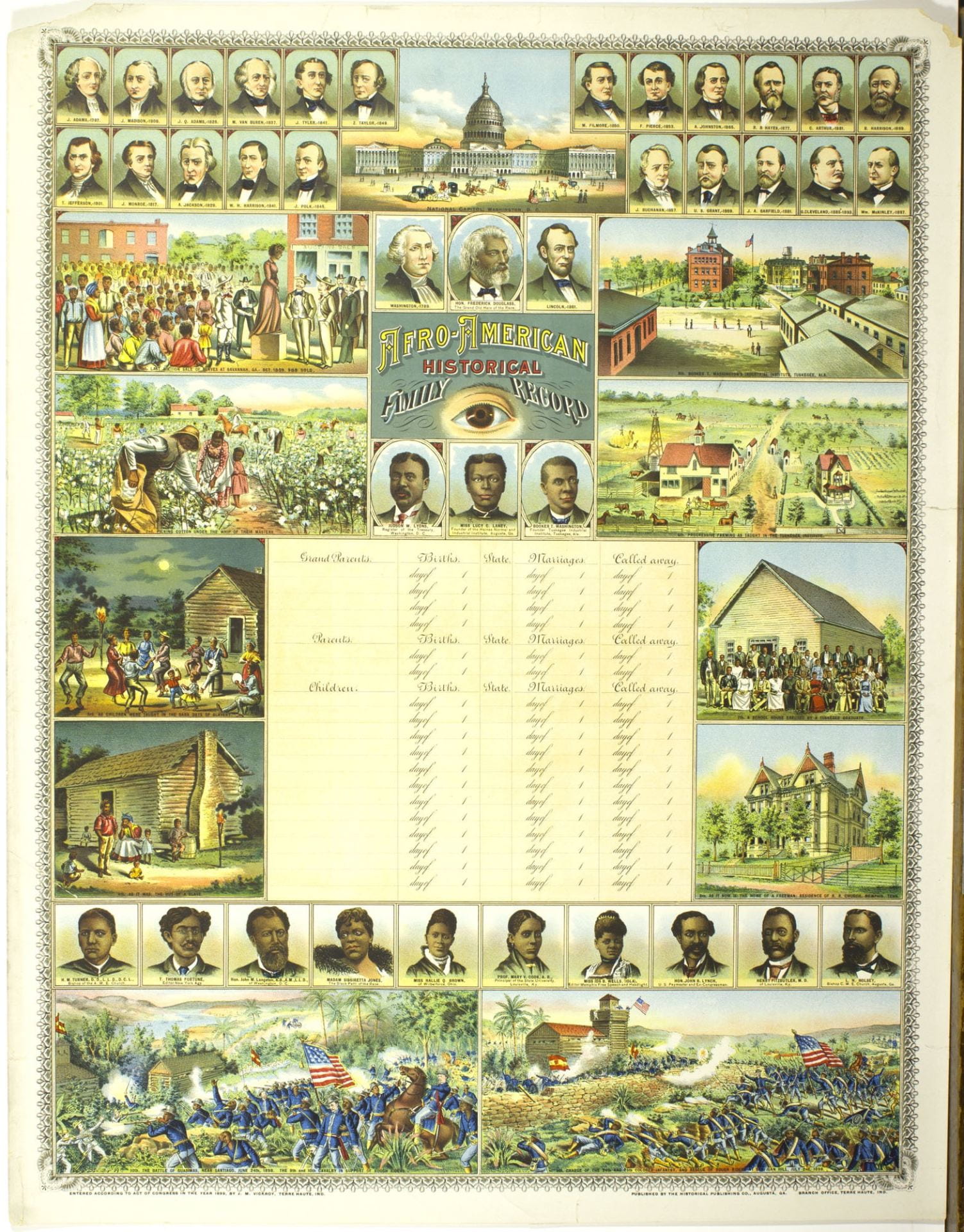

Despite this, a subgenre of family records emerged dedicated exclusively to African Americans. In keeping with the ideals of the Colonial Revival, typical African American family records included imagery that enmeshed the individual owner and recorder within a larger national identity. One Afro-American Historical Family Record created in 1899 by J.M. Vickroy & Co. is rich with imagery. Surrounding the text block at the center, Vickroy includes both narrative scenes on either side and portrait busts of national figures both above and below. Among these portraits are likenesses of both white and black politicians and civic leaders: on a larger scale, Frederick Douglass appears between George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, below a gallery of American presidents (all white) and above a row of African-American politicians who assumed office during Reconstruction. With the Capitol Building at the top center of the sheet and the Eye of Providence, a motif taken from the Great Seal of the United States, at its heart, Vickroy seems to be arguing that African Americans had an equal claim to a national identity as white Americans.

James M. Vickroy, Afro-American Historical Family Record, c. 1899. Chromolithograph, 27 x 21 in. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Given that the Eye of Providence also appears on Vickroy’s other printed documents, including a family record intended for a less-specific, likely white audience, Vickroy unifies his many patrons under a common iconographic schema. While it first emerged as a Christian motif, today the Eye of Providence is most closely associated with Freemasonry. Prior to establishing his own lithographic firm, Vickroy had worked for M.C. Lilly Co. in Columbus, Ohio which catered to fraternal organizations in its marketing of swords and charts. In 1885, for his new establishment in Terre Haute, Indiana, Vickroy’s first product was a lithograph designed for the Independent Order of Odd Fellows. By 1904, he had obtained the rights to charts that he had designed for twenty-eight fraternal organizations, demonstrating the extent of the market dedicated to such communal societies at the time. But the presence of the Eye of Providence in the context of the Afro-American Historical Family Record is likely not intended to invoke a fraternal organization such as the Freemasons as this would have restricted the demographic of the record only to African American Freemasons. By using the same format as he would for a membership certificate, with a blank document surrounded by depictions of historical scenes and figures with emblematic significance, Vickroy seems to have been suggesting that a sense of belonging to the African-American community served a similar role to membership in a fraternal organization.

Vickroy did not have a monopoly on family records and the collection at the Library of Congress, which holds the many family records that were submitted for copyright, represents other publishers including Krebs Lithographing Company, the Chapman Brothers Lithographic Company, Lehman & Bolton, and the Merchant’s Lithographing Company, firms that also produced other paper goods for useful purposes such as billheads, letterheads, advertisements, and maps. Like Vickroy, other publishers identified niche groups with specially designed and titled family records, including Nathaniel Currier who created a family record in the German language. Some family records though were simpler in design, using allegorical and religious images of plenty such as bundles of fruit and trumpeting angels. These motifs recalled fraktur birth and marriage certificates which served comparable functions, tracking family formation, in another early-American ethnic group, the Pennsylvania German community. Others, including the more standard family record produced by J.M. Vickroy & Co., featured emblematic scenes progressing from birth to the process of undertaking an education and engaging in courtship rituals through the final acts of aging and death, such as one family record by Strobridge & Co. that is embellished with Thomas Cole’s Voyage of Life series. Another popular layout relied not on a central written record but on blank ovoid frames intended to house photographic representations of ancestors, recreating the effect of a gallery of ancestral portraits. Furthermore, a family record showing frontier life published by the Moline Plow Company, suggests family records functioned in a similar way to calendars of the era, which were frequently commissioned by a range of businesses as complimentary giveaways to reward loyal customers and broadcast their name. That Vickroy and other printers produced family records for a niche audience shows how manufacturers acknowledged African Americans as an equally valuable group of consumers and potential clients in the early years after the Civil War as other white patrons.

For those who were inexperienced with the process entailed in mapping out a family history, the formulaic Afro-American Historical Family Record would have been user-friendly. Labeled lines dictated what information was important, serving as implicit instructions to document the date and place of the births and marriages for the owner’s two preceding generations of ancestors. The makeup of the African-American family transformed after emancipation. In the era of enslavement, such statistical records of genealogical information would have been the domain of plantation overseers who used record books, offered in standardized, printed versions, to correlate enslaved people’s physical bodies with their production and thus maximize profits in accordance with the ideals of scientific management. With freedom came the permission for the formerly enslaved individual to make personal health and reproductive decisions, and to elect whether to record that information. Although they continued to be excluded from the federal census until 1870, African Americans might have been exposed to record keeping through their churches which oftentimes maintained careful accounts of the births, marriages, and deaths of their worshipers. In the period, it was common to scribe family trees at the opening of the family bible, a possession even the poorest often claimed as their own. Harper’s 1846 Illuminated Bible incorporated a page for marriages into its layout. In addition, African Americans who had served in the Civil War would have been familiar with the practice of logging their personal physical and bodily condition. These precedents might have inspired formerly enslaved individuals to develop their own written records of personal ancestry.

In some ways, these family records were designed as a means for African Americans to celebrate their ability in freedom to research and record their family history. African Americans reclaimed information about their reproductive pasts. But while Vickroy’s design for the Afro-American Historical Family Record matches that of generic family records, suggesting that African Americans have an equal right and ability to record and take pride in their heritage, by conforming to this layout, it also glosses over the tragic history of control imposed upon African Americans during slavery. There is no place on this all-too-perfect document for the restrictions on marriage, threat of family separation through sale, the emphasis on maternal rather than paternal lines, and role of rape and other forms of sexual violence that typified the enslaved person’s experience. The blank lines establish the expectation of familial knowledge. African Americans would likely have had to rely on orally transmitted memories, rather than written documentation, for knowledge about the older generations in their family trees. Left empty, they would have been painful reminders of lost records and holes in an individual’s legacy. Perhaps this is why the record only acknowledges the two preceding generations, rather than looking deeper into time. Instead, with a standardized number of lines—four for the grandparents and two for the parents but twelve for the children—the layout looks to the future, promising continued growth and development of the African American community.

The record’s design, which is replete with visual imagery of the historical past, may also be intended to compensate for lacunas in an individual’s knowledge of his or her familial past. By using narrative vignettes that align with other historical tableaux dedicated to the theme of racial progress, Vickroy establishes a generic substitute for an individual’s ancestors’ personal experiences. Other pictorial narratives dedicated to the history of racial progress could have served as Vickroy’s precedent, including, perhaps the first by an African American artist, James Presley Ball’s panorama and many of the narrative series that followed it, such as Meta Warrick Fuller’s set of tableaux for the 1907 Jamestown Tercentennial. Vickroy began his history not with the arrival of the first enslaved people in America at Jamestown in 1619 like his precedents but with the more recent history of an 1859 auction, occurring just before the start of the Civil War, a historical moment that might have been within the recordable personal memories of buyers in 1899 and one that mapped onto the life-spans of the four generations encompassed by the blank record.

Eight scenic vignettes show a slave auction, enslaved workers in cotton fields, a circle of enslaved dancers and musicians, slave quarters, Booker T. Washington’s Industrial Institute at Tuskegee, farming at Tuskegee, a school founded by a Tuskegee graduate, and the stately home of the freeman Robert Reed Church. The series uses both generic and specific imagery, but in broad terms moves from the more universalized enslaved person’s experience, picking cotton, through the more exclusive opportunity of attending the Tuskegee Institute, to the final endpoint, a home associated with a single individual, Church, the first African American “millionaire” in the South who built his wealth by founding a bank and trading land.

The movement of imagery in the series with the progress of time from generic to specific aligns with the common shape of an individual’s family tree. As ancestry is traced backwards, it exponentially expands to encompass both maternal and paternal lines with each ensuing generation. Individuals, charting their genealogy, broaden their definition of self and abstract their ancestors’ experiences as they look further back in time. Not only is information generalized across a larger group of individuals, with the distance of time, less information is available about each individual. This tendency would have been compounded for African Americans who might not have had any evidentiary written records of specific individuals in their own family history. Thus, the progression in the imagery from generic to specific might have accorded with the knowledge owners of this family record had of their own ancestors. However the trend toward more specific imagery in the contemporaneous era works in opposition to the record’s other imagery related to civic pride. While the patriotic motifs are intended to enlarge the definition of national identity so that it encompassed African Americans, the historical vignettes work in a restrictive fashion, establishing a proper ideal of African American character with the final vignette of Robert Reed Church, one that privileges education and wealth.

Similarly, the style shows a gradual evolution from more generic representations of figures to more individualized ones. For the first vignette in the series, referencing to “The Great Slave Auction” in which the enslaved people of Pierce Mease Butler were sold in Savannah, no depiction of the sale seems to have existed as an archetype, so Vickroy likely relied upon standardized tropes for the depiction of slave auctions, showing the scene occurring out of doors and centered around a raised auction block, a pattern of representation that Maurie McInnis proves did not accurately capture the circumstances of all sales. In this first vignette, as the figures recede into the background, they become increasingly generic, lack detailed delineation of their clothing and features, and are shown in less saturated colors, again suggesting the image is derived from the artist’s imagination.

The second image in the series, dedicated to cotton picking, has a generic title that describes a common enslaved person’s experience collecting cotton under the supervision of the overseer. But unlike the first vignette, this second one has a detailed depiction of a figure in the foreground shown with an expression of intensity and specificity. Vickroy based this image on an Eagle Post Card View by published by Fred R. Martin in 1890, titled “WORLD’S MOST FAMOUS COTTON FIELD SCENE / ALABAMA’S ALEXANDRIA VALLEY ABOUT 1890.” Appropriating the figures and positioning of emancipated slave hands in a cotton field, Vickroy uses the postcard as a template but adds more laborers as well as two distant figures on horseback, the masters his caption refers to, crafting an expected, standard image of the past out of a specific and more contemporary archetype. Here, the landscape and the vision of life in the antebellum South become a surrogate for absent specifics. Because the landscape is based upon a contemporary view, it would serve as a stable, recognizable, and even personally familiar line of continuity for the owners of the family records between their own lives and those of their invented ancestors. In this case a generic representation of agricultural laborers interacting with the land, one falsified and based on a contemporary photograph, facilitated owners’ imagined connections to past generations.

World’s Most Famous Cotton Field Scene / Alabama’s Alexandria Valley about 1890, c. 1890. Postcard, 5.6 x 3.4 in. Alabama Department of Archives and History.

Vickroy used the photographic illustrations in James T. Haley’s Sparkling Gems of Race Knowledge Worth Reading: A Compendium of Valuable Information and Wise Suggestions That Will Inspire Noble Effort at the Hands of Every Race-Loving Man, Woman and Child for both his portraits and historical vignettes, even retaining their captions. Haley’s book includes photographs of both a slave dwelling and Church’s residence which became the fourth and eighth vignettes. Vickroy manipulates these photographs and while Church’s residence is only slightly idealized in comparison to its photographic source, shown without a telephone pole and with more and lusher trees and a wider surrounding yard of greenery, the fourth scene is radically transformed. While both show an enslaved family outside of its presumed abode, Vickroy replaces the photograph’s isolated and disparate groupings of figures at the doorway, bench, and ladder with a single gathering of a family in the front yard. Haley, an African American author, intended his self-published book to counteract negative white stereotypes, especially those spread during the Tennessee Centennial. The illustration in Haley’s book captures the figures’ highly individuated responses to the camera’s lens. But the potential resistance of the figures represented in Haley’s book is lost when Vickroy transforms the photograph into a more expected, generic family scene in which figures face inward toward one another rather than outward, interacting with the viewer.

“AS IT ONCE WAS—THE LIFE OF A SLAVE,” from James T. Haley, Sparkling Gems of Race Knowledge Worth Reading: A Compendium of Valuable Information and Wise Suggestions That Will Inspire Noble Effort at the Hands of Every Race-Loving Man, Woman and Child (Nashville, Tenn.: J. T. Haley & Company, Publishers, 1897). Project Guttenberg.

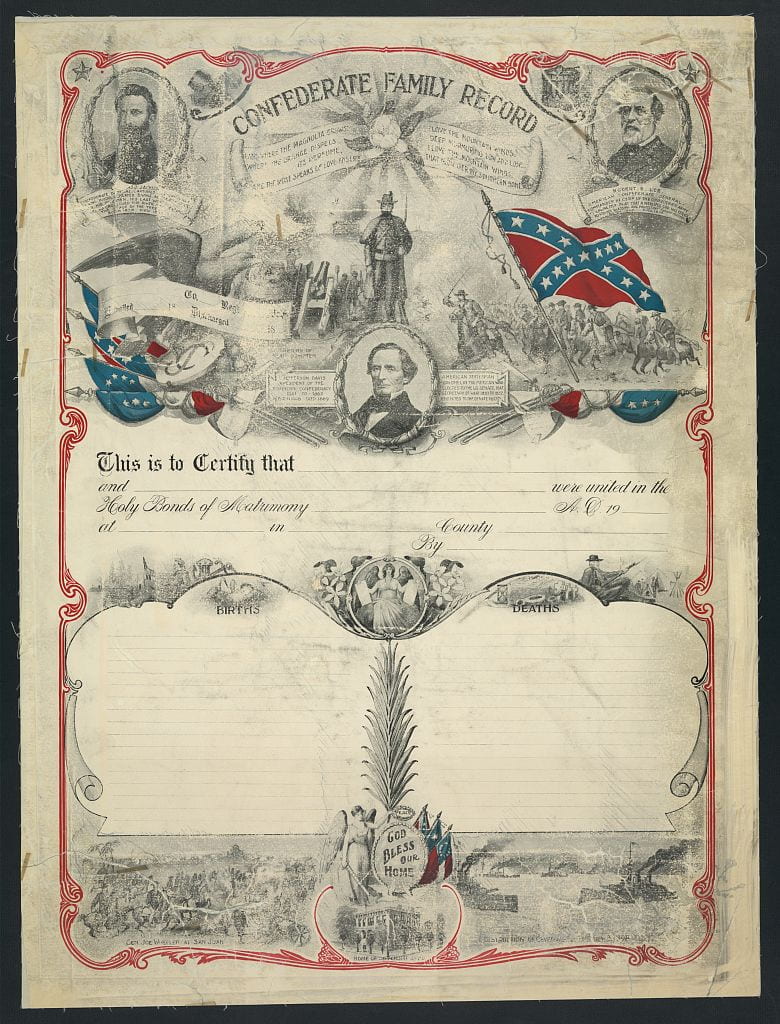

The most striking contrast to Vickroy’s Afro-American Historical Family Record in the Library of Congress collection is the Confederate Family Record. Like the Afro-American Historical Family Record, this record includes depictions of historical figures—Thomas J. Jackson, Robert. E. Lee, and Jefferson Davis—as well as historical scenes. Genealogy continued to be an important subject for those mourning the loss of the Confederacy, as a genealogical tree of the Lee family published in 1886 attests. In the Afro–American Historical Family Record, the Civil War is a pivotal turning point, marking the divide between the four historical vignettes on the left side of the written record and the four on the right. In contrast, the Confederate Family Record fails to acknowledge that the war has concluded. While some of its scenes are historical and refer to the Civil War, like one depicting the capture of Fort Sumter, the document also suggests a narrative of progress, continuing into contemporaneous representations of the Battle of San Juan Hill and the destruction of Cevera’s Fleet, both of which occurred in 1898 as a part of Spanish-American War. While today, the narrative of the Battle of San Juan Hill holds significance as the moment when the Rough Riders, and Theodore Roosevelt, achieved fame, to the owners of the Confederate Family Record, the battle demonstrated the continued triumphs of Joseph Wheeler, a former Confederate Army general.

Strikingly, the Spanish-American War is also the subject for the bottommost vignettes in Vickroy’s Afro-American Historical Family Record which depict the Battle of Guasimas, when the 10th cavalry of African American “Buffalo Soldiers” came to the aid of the Rough Riders, and another moment in the Battle of San Juan Hill, when the 24th and 25th Colored Infantries again fought alongside the Rough Riders. These family records position former-Confederate and African American soldiers as integral contributors to the American victory in the Spanish-American War, selectively quoting from the same moments in history to tell very different stories.

While the family record was produced at a time of deep fear of miscegenation, Vickroy seems to make a case for the opposite, visually intermingling portraits of individuals from both white and African-American communities and championing the values of Booker T. Washington, who argued for an assimilation of white social standards. This imagery may be defiant, forecasting a hopeful future of an equal and peaceful coexistence between people of different heritages in America. But it also minimized the enduring struggles, following emancipation. The expectation that African Americans would easily adopt the fashionable practice of ancestral research ignored the ongoing burdens formerly enslaved individuals continued to face following emancipation. That this and other records remain blank may suggest African American consumers were not interested in Vickroy’s design and engaging in the project of imagining their genealogical past.

Leave a Reply