Three Hundred Years of Secrets

By Erin Anderson, WPAMC Class of 2020

One of the oldest desks in Winterthur’s collection is a beautiful walnut slant-front desk in the William and Mary style. Yet, despite being three-hundred years old, this desk still had some secrets left to be revealed…

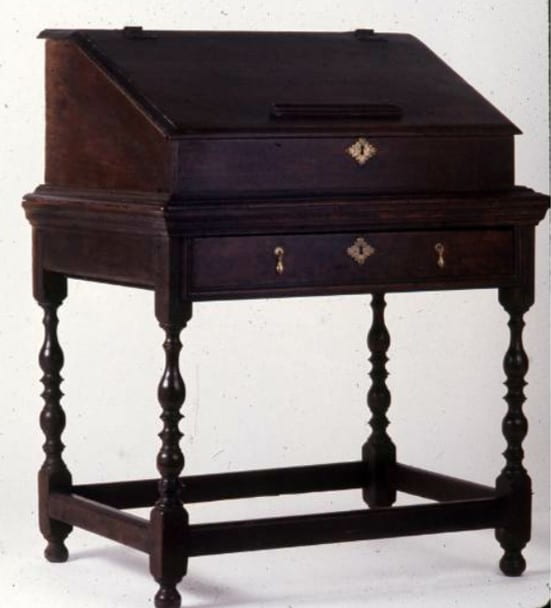

Figure 1: Desk, 1700-1725, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Winterthur 1958.0561, Gift of Henry Francis du Pont.

Slant-front desks are essentially an evolution of older forms of furniture. Desk boxes, also called “Bible boxes” were semi-portable writing surfaces. These were followed by the desk on frame which essentially fitted a desk box onto a standing frame, elevating it to a height at which one could sit and write comfortably. Escritoires, sometimes also referred as bureau cabinets, are similar to a slant-front desk in that they combine a chest of drawers and a desk, however, the innovation of the slant-front desk which the escritoire does not fully achieve is to integrate the drawers and writing surface into a single carcase.

Figure 2: Desk on frame, 1690-1715, Massachusetts, Winterthur 1958.0697, Gift of Henry Francis du Pont.

Yet, in the early eighteenth-century these desks are still relatively rare. If any flat surface can be used for writing, why spend money on a specific piece of furniture just for that? The ingenuity of a desk it that it is really a new form of storage. The addition of small drawers, pigeon holes, and central prospects meant owners could store papers, trinkets, and valuables with a greater degree of organization than one could in a cavernous chest. More than likely, the original owner of this desk was Joseph Richardson Sr. (1711-1784) one of the eighteenth-century’s premier silversmiths based in Philadelphia. Richardson probably valued this desk for its fine construction and would have used it to organize records and papers related to his business.

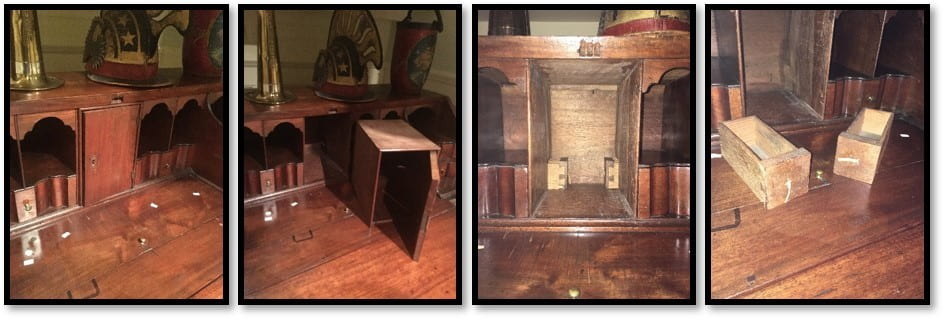

It is possible that Richardson may have also been storing valuables in the desk – a common enough practice for the eighteenth-century. The desk has locks on the lid and lower drawers. The two upper drawers in the case were designed with concealed locking mechanisms built into the underside of the drawer. To further thwart potential thieves, the prospect can be removed completely, revealing two small drawers concealed behind; and the side drawers can be removed to access a pair of small boxes hidden in the recesses of the desk.

Figure 3: Hidden drawers behind the prospect in Winterthur’s slant-front desk. Photographs by the author.

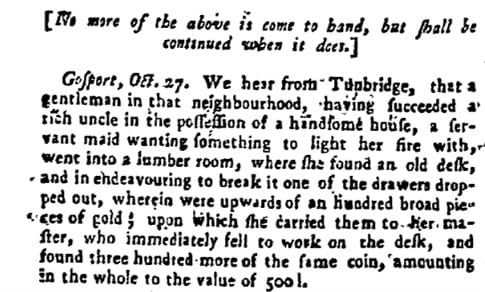

It can be hard to know exactly how “secret” these drawers actually were in the eighteenth-century since many desks were made with similar patterns of hidden compartments. If we believe the amazing tale printed in the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1749, then it does seem possible that valuables could remain concealed for many years without being detected.

Figure 4: An article from the Pennsylvania Gazette, February 14, 1749 detailing the discovery of several hundred gold coins within an inherited desk.

But three-hundred years is a long time to keep a secret, so imagine my surprise upon opening up one of the secret drawers and finding a hidden note!

Inside was a short note from a graduate of the program, Lois Dietz (now Lois Stoehr), who continues to work at Winterthur today as the Associate Curator of Education. I got in touch to let her know that her note had finally been found after more than fifteen years, and we shared our mutual appreciation for this delightfully secretive desk. Finding the note was a fun way to reconnect with Winterthur fellows from years past and to bond over the joys of close-looking, connoisseurship, and the joy of hidden treasures.

![A small piece of note paper on which is written ““This desk greatly increased my appreciation of early 18th-c[entury] furniture. I hope it has done the same for you! Lois Dietz WPEAC ’04.”](https://sites.udel.edu/materialmatters/files/2019/05/Figure-5.jpg)

Leave a Reply