Unfinished Business: Signature Quilts and their Creative Process

By Emily Whitted, WPAMC Class of 2020

Up close and personal in the textile study lab with Winterthur’s 1857 30 block applique signature quilt from Harrison, New York.

I have a basket in my house filled with half-done sewing and knitting projects. I’ve got two pairs of hand-knit socks that need finishing, some mittens that I’ve run out of yarn for, an unhemmed skirt, and some personal designs sitting stagnant in their patterning process. I’d happily prefer it if the public never saw my basket full of unfinished projects, but you’d learn much more about my process midway through if you did. Catching a historical object in a state of incompleteness is rare: it seems counter-intuitive to preserve something that technically isn’t finished, especially when its original maker isn’t around to complete it. When trying to determine which object in Winterthur’s collection I should choose to spend serious quality time with through the fall, I paused at a set of five unfinished applique quilt squares from the mid 1800s, three of which are signed by their makers. I was immediately attracted to their state of unfinishedness. Who were the women who made them, and why didn’t they find their way into a finished quilt?

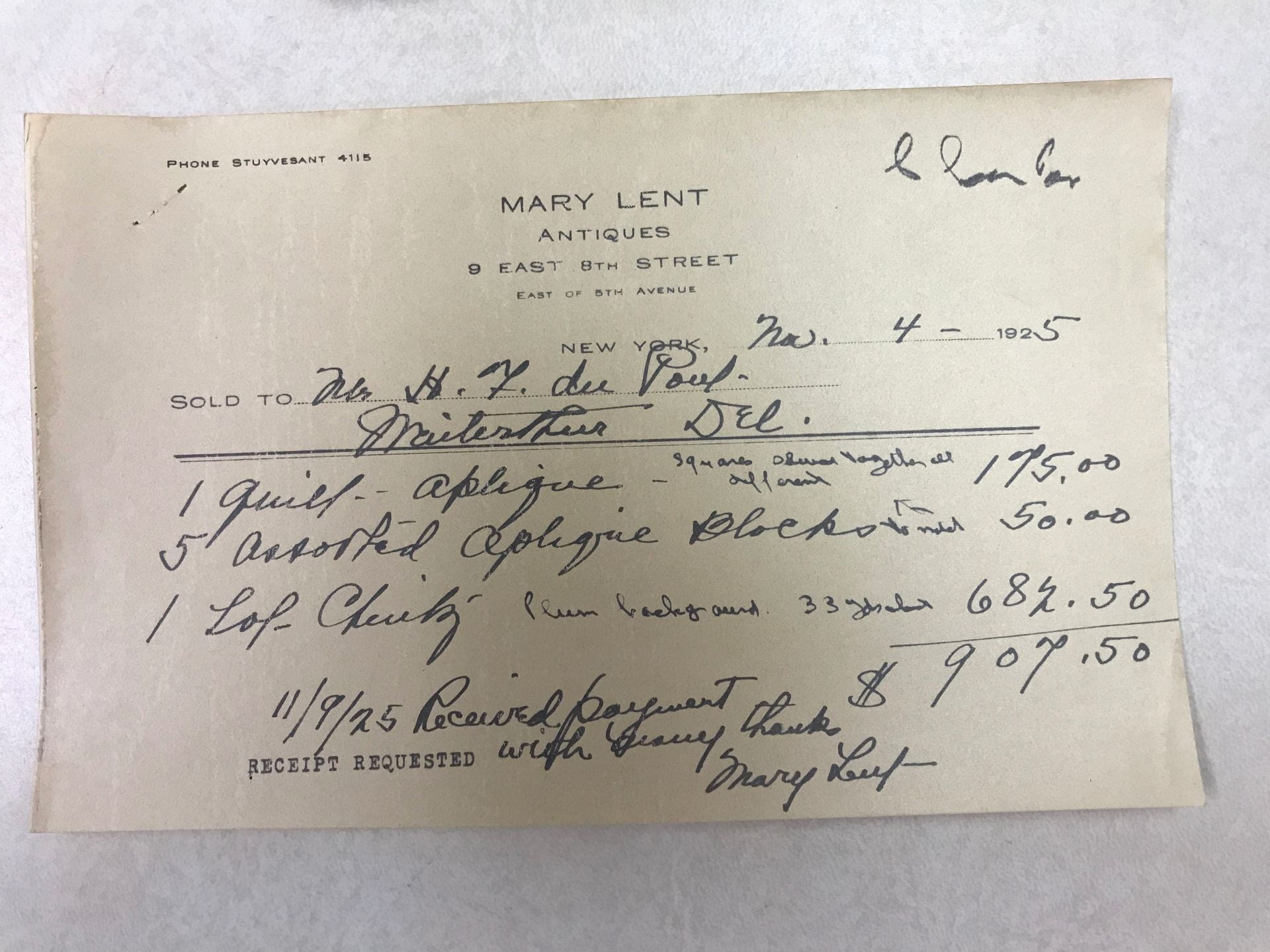

A bill of sale from Mary Lent, antique dealer, to H.F. du Pont on November 4, 1925 for “1 quilt – aplique, all squares sewn together all different” and “5 assorted aplique blocks to match” for $225.00.

The quilt squares turned out to not be entirely alone; H.F. du Pont purchased them in 1925 along with an 1857 appliqued signature quilt from Harrison, New York with over 30 individual blocks and 14 signatures. Bearing striking resemblance to each other in color scheme, material, and sewing techniques, the unfinished quilt squares seem to have been left behind in the design process for this finished quilt.

The quilt spans at least four family groups within Westchester County, New York, all with their own distinctive sewing methods and signature styles. Two family groups, the Mekeels and the Meads, were likely cousins. Letters between H.F. du Pont and the dealer who procured these squares and quilt, Mary Lent, reveal that 19 unfinished squares had originally been sent, but H.F. only kept 5 and returned the remaining 14. While the purpose of his purchase is not known, the aesthetics of the quilt and separate squares are in the style of quilts he was buying to furnish his Southampton home at the time.

They belong together: the 5 unquilted blocks line up neatly at the top with the finished quilt, and blend pretty seamlessly. Too bad they didn’t make the cut!

The design process of a signature quilt with multiple makers is infinitely more complicated than a quilt made by one person; to piece and quilt the final product, all makers need to actually complete their squares. To preserve cohesiveness, usually the finished squares from each participating woman would be compiled by one or two women at most, who could have strong feelings about the layout and caliber of the designs. With no true center square or clear focal point on any one signature in this finished appliqued quilt in Winterthur’s collection, it is difficult to determine the intended recipient of this quilt, and for what purpose. Signature quilts could be pieced in honor of a major life event, such as a woman’s marriage or departure from a geographical area, a birth of a child, or a death of a family member. Family reunions were also common settings for signature quilt making. With these events came the pressure of time, and not making the deadline could mean not making it into the quilt. Perhaps the reason these squares never made it into the final quilt was simply because their makers ran out of time? I hope to spend my fall digging deeper to the lives of the women who made these squares and take full advantage of glimpsing a creative process in a state of unfinishedness.

Leave a Reply