A Symphony of Color [Theory] in Mary Gartside’s Essay on Light and Shade

By Joseph Litts, WPAMC Class of 2020

Winterthur is very lucky to have a copy of Mart Gartside’s An Essay on Light and Shade on Colors and Composition in General. Gartside published two additional books: An Essay on a New Theory of Colours, and on Composition in General (1808) and Ornamental Groups: descriptive of Flowers, Birds, Shells, Fruit, Insects, &c. (1808), though all three are incredibly rare. Printed in London in 1805, Light and Shade is gorgeous and fascinating. As she describes in the opening pages, Mary Gartside was a drawing teacher, frequently frustrated by students who were “desirous of beginning immediately to paint,” but without a fundamental understanding of the principles of light, shadow, proportion, and color.[i] Drawing and painting in watercolors was a popular past-time for well-educated merchant and gentry classes in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Many became professional teachers of the subject, like Gartside. This was a reasonably respectable way for society women to earn income.[ii]

Cover, Mary Gartside, An Essay on Light and Shade on Colors and Composition in General (London, 1805). Winterthur Rare Books, NC735 G24. Photo by author.

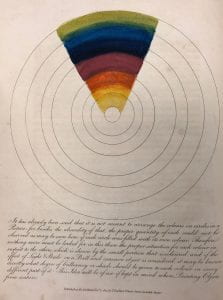

Gartside used her medium of watercolor painting to engage with contemporary debates on color. Her understanding of color and color theory is the significant contribution of her book. She recasts both Isaac Newton’s theory of prismatic color and Sir William Herschel’s theory of radial color by creating a “color ball” that wraps the chromatic prism into a continual spectrum. Such a color ball anticipates Goethe’s attempts to put color into wheels, a shift from earlier grid representations. [iii]

Gartside’s Color Ball, from Essay on Light and Shade. Photo by author.

Much like Goethe, though, Gartside was interested in quantifying and describing various color-related phenomena, particularly how various colors advance and recede. She demonstrates this through a series of 8 breathtaking “plates” that are actually unique watercolor paintings. These were intended to “to demonstrate the compositional effects of the seven prismatic primaries” in a period just before color lithography would change the dissemination of works on color and just before synthetic dyes would change the course of color theory itself.[iv] Earlier artists had unsuccessfully grappled with reproducible color, with the most common solution to add color to black and white prints by hand with watercolors, a laborious process that gave variable results.

Detail of “Figure 5: Scarlet,” from Essay on Light and Shade. Photo by author.

The book captures the struggles of printing and publishing such works on color in the early 19th century. More importantly, the book documents women’s engagement with scientific and aesthetic theories within socially-defined acceptable roles such as watercolor painting. Indeed, “Gartside appears to have been the only female writer of partly theoretical treatises on colour, albeit in the respectable guise of a painting manual.”[v] Painting and drawing provided a veneer of decorum to intellectual pursuits, not only for Gartside as author, but also for her readers. This book is an important testament to such methods of knowledge production.

Image of “Figure 2: Yellow,” from Essay on Light and Shade. Photo by author.

[i] Gartside, pp. 1–3.

[ii] Ann Bermingham, Learning to Draw (New Haven: YCBA, 2000) p. 215.

[iii] See Patrick Baty, Anatomy of Color (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2017) pp. 124-7. Baty notably does not cite her work.

[iv] Bermingham, Learning to Draw, p. 219.

[v] Alexandra Loske, “Mary Gartside: A female colour theorist in Georgian England,” St Andrews Journal of Art History and Museum Studies, Vol. 14 (2010) p. 18.

where can you buy the book

I would love to obtain a copy or download of this essay for my mother for Mother’s Day if possible. You may reach me at loveinthecloud@icloud.com . Thank you so much!