Visions of the High Life

By James Kelleher, WPAMC 2020

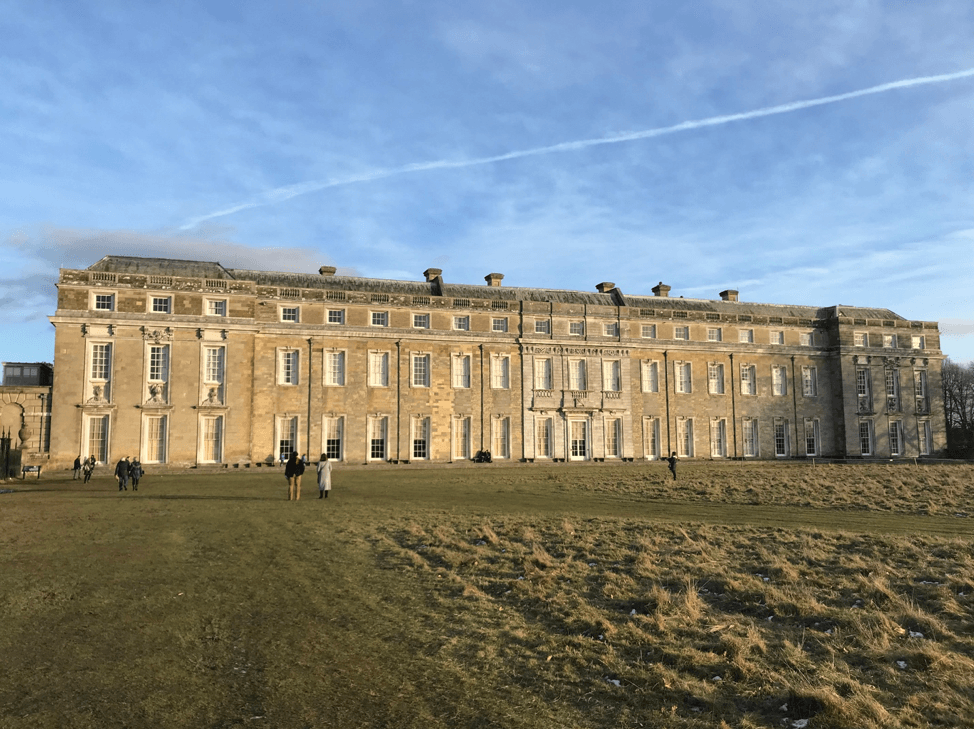

Certain symbols of luxury have come down to us from past centuries relatively intact. I suspect almost anyone in the world, regardless of their familiarity with architecture or English history, could see a photo of Petworth house (above) and correctly surmise that it was an elite dwelling. Both its size and ornamentation are cultural shorthand, even today, for luxury. Interior photos would elicit the same response: elaborate ornament, spacious rooms, and fine paintings all speak a language of luxury. It’s the language of Versailles and the Breakers, a visual lexicon of gilt excess that has escaped historical context and settled comfortably into our popular imagination.

The trouble, of course, is that the languages of luxury and status have constantly evolved throughout history. If we travel far enough, or go back in time long enough, we’ll quickly start to lose the dialect. On the last full day of our British Design History course, we experienced two houses, separated by more than two and a half centuries, presenting radically different visions of luxury. We ended the day with Petworth House, built in the late seventeenth century, in many ways an archetypal English country house with an expansive landscaped designed by Capability Brown. Nuanced as the house’s details may be, the broad strokes of aristocratic wealth, land ownership, and patronage of the arts are still legible. Our morning before Petworth offered as a more challenging, and to my mind more interesting, vision of the high life.

We spent our morning at the Weald and Downland Living Museum, a collection of vernacular buildings spanning the past 900 years of architecture in the southeast of England. The museum collects buildings from the surrounding area that would otherwise be subjected to demolition, removes them, and reconstructs them on their site, resulting in a physical timeline of local building traditions that simultaneously reflects broader changes in English housing standards. A jewel among their collections is the Bayleaf farmhouse, an early Tudor hall house restored and furnished appropriately to the 1530s.

Few visitors would walk into Bayleaf and think luxury. The unglazed windows, the central great hall open to the rafters, the exposed framing are too foreign to modern sensibilities. Even the chimneyed fireplace, the quintessential emblem of domestic comfort, is absent in favor of its predecessor the open hearth. In reality, the great hall was built for a wealthy yeoman farmer. It was more than twice the size of the typical English home. Within the house are both uncommon conveniences (an indoor privy, several private rooms adjacent to the hall) and also ornament (the molded crown post in the solar wing, a jettied second story). For a wealthy farmer, this was a grand house. Petworth is not a particularly apt comparison; the more natural choice would be Hampton Court Palace, a roughly contemporaneous structure. The difference between Hampton Court’s Great Hall and that of Bayleaf is one of scale rather than form. Both are luxury in a different register: not the luxury of Petworth, even less that of today’s elite homes, but a luxury stretching back to the medieval era that breathed its last in the sixteenth century.

Most people probably know that notions of luxury are socially constructed, even if they don’t think about it. But there’s a real power to being physically confronted by that fact: feeling the breeze through the high windows of Bayleaf’s great hall, walking around the fire burning on the stone floor, smelling the smoke drifting up to the visible rafters, and realizing that this space now so foreign to modern sensibilities was once a space of relative luxury.

Leave a Reply