An Early American Friendship Brooch

By Anastasia Kinigopoulo, WPAMC Class of 2020

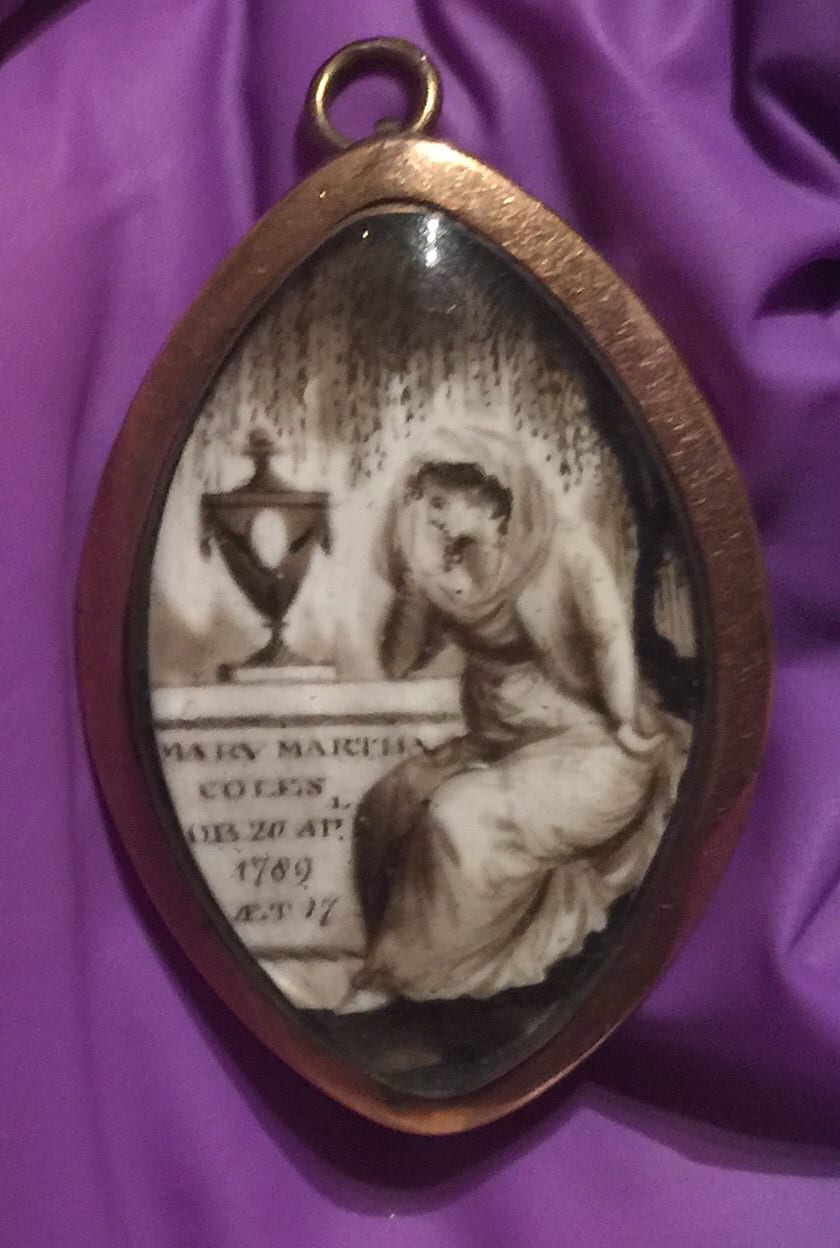

Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Mourning pin, 1785-1820, United States, Gold, Ivory, Gift of Roland E. Jester in memory of Margo Jester, 1981.101

I had a funny feeling about this brooch ever since my classmate, Erin Anderson, pointed out that the enamel was blue, not black, as one would expect of a mourning brooch.

This beguiling little item came into the Winterthur Collection in 1981. It incorporates tiny pieces of cut hair in the miniature painting, specifically on the column and ground beneath the figure. Today, we often lump “hairwork” jewelry with mourning jewelry regardless of its original purpose, perhaps because we now find both the preservation of hair the materiality of death disconcerting. However, these objects were not always used to commemorate the deceased. Though it can be difficult to tell the difference between jewelry made to celebrate a relationship and that made to memorialize the dead, aspects of this brooch hint toward the former interpretation.

Mourning pin, 1785-1820, United States, Gold, Ivory, Gift of Roland E. Jester in memory of Margo Jester, 1981.110 (Photograph by the author, courtesy Winterthur).

Like a number of other examples at Winterthur, late 18th century mourning jewelry typically featured specific iconography—urns, weeping willows, sobbing classical figures—and inscriptions referring to the dead. These symbols marked the beginning of an era when men and women viewed sentimentality as a highly desirable trait. But in the to friendship brooch, symbols associated with death are conspicuously absent. The woman appears to be smiling, and the birds, which often represented the soul, seem little inclined to fly off toward heaven. Based on this and on the inscription on the banner, it’s possible that this brooch was presented as a token of companionship rather than clung to as memento of heartache.

Who were the people that exchanged such gifts? Owners of hairwork jewelry in England and North America were typically white men and women with the economic means necessary to commission custom-made jewelry from a professional. Given that this particular brooch is of English origin, if the owner was North American, they would have sent a lock (or locks) of hair abroad to a London jeweler to be incorporated into the design.We can also surmise that this person would have valued the expression of sentiment that led them to commission this object in the first place.

As scholar Helen Scheumaker points out, the gifted brooch would have served as a declaration of both wearer and giver as “individual(s) of deeply felt, sincere emotions.” Because the individuals referred to in the inscription are not immediately obvious, this tiny object would have allowed the wearer to signal their involvement in a private circle, accessible only to those “in” on the meaning. This would have been all the more true if the owner wore this pin face down over their heart, as was occasionally the custom in America. Though odd to us now, this little brooch and the hair contained within would have been a sweet affirmation of warmth between people alive over two hundred years ago, so very much like the friendship jewelry of today.

Leave a Reply