What a Project: Summarizing the World’s Knowledge

By Olivia Armandroff, WPAMC Class of 2020

Naturall, & Morall Philosophy, 1686–1710, etching and engraving on paper. Part of The Gentleman’s Recreations, Richard Blome (publisher). Winterthur Museum, 1973.0585.015.

In the Winterthur Collection is a set of seventeen illustrations, each dedicated to the representation of a different discipline of knowledge. They were printed by seventeenth-century English publisher Richard Blome. Their complex imagery includes titles, dedications with coats of arms, vignettes, icons, and large, central ellipses, enclosing diagrams. When I first encountered these prints, their diagrams reminded me of flow charts, organizational schemes pioneered in the early twentieth century by advocates of scientific management. Flow charts are intended to streamline work and promote efficiency; Blome’s charts use a similar framework of curving lines and bubbles to trace the emergence of subfields, innovations, and terminology in disciplines of knowledge.

The seventeen prints are part of a larger publication first released in 1686 by Blome, The Gentleman’s Recreations, that sought to compile the learning necessary for his elite readers, and much of his text and diagrams were adapted from a 1587 encyclopedia by Christofle de Savigny. Some of the diagrams and their corresponding chapters are dedicated to the traditional liberal arts and sciences which had long served as the primary basis for encyclopedic texts. Others demonstrate Blome’s expansive definition of knowledge that included the mechanical arts, such as navigation and agriculture, reflecting the ideas of Francis Bacon who in the 1600s argued that knowledge could be found in the world and not merely in texts. Blome enhanced the scope of his publication to appeal to his readership too, people such as the over-two hundred British gentlemen subscribers who sponsored it, with diagrams on subjects such as heraldry.

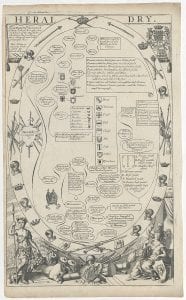

HERALDRY, 1686–1710, etching and engraving on paper. Part of The Gentleman’s Recreations, Richard Blome (publisher). Winterthur Museum, 1973.0585.010.

In a close look at Blome’s print, Heraldry, an allegorical scene occupies its base. Armored Roman warriors hold lances, a cornucopia, and a shield. Between them lies an array of artfully composed military paraphernalia, from cannons, to armor, to flags, to drums. Above the scene, the ellipse’s border is adorned with a knight’s tools, including various swords, helmets, and crowns. At the center, Blome summarizes heraldic teachings by diagraming regulations like abatements (the modification of a coat of arms); illustrating examples of heraldic patterns such as different borders and lines; and categorizing ancient and more modern heraldic traditions. This information is captured in various shapes—ovals, rectangles, and a shield-shape—and connected by fluid, curving lines. While there is a flow in the diagram, its curving branches seem to suggest there is no single way to read the diagram, embracing the creativity and individuality of the learning process. But by capturing the information in an ellipse, Blome claims to represent the discipline as a whole, recalling how the ancient Greeks understood the term, “encyclopedia,” as instruction in a complete system or a circle. Ultimately, the elliptical form resembles the human brain, an apt container for the reader’s newfound knowledge.

The idea of incorporating knowledge into a visual diagram was not new. With a brain-like shape, Blome’s container is inspired by nature like many others. Trees have long been a common mode of visualizing knowledge. Beginning with Peter of Spain’s publication of Tractatus in the thirteenth century, students of logic were instructed with the visual metaphor of the Tree of Porphyry.

“Tree of Porphyry.” Part of Peter of Spain, Tractatus. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

In contrast, Trees of Consanguinity, which captured blood relationships, were sometimes superimposed on the human body. At their height in the seventeenth century, the Jesuit scholarly form of the thesis print summarized the essentials of Aristotelian scholastic logic in complex scenes, such as Martin Meurisse’s Artful description of logic in its entirety, which incorporates teachings into the framework of an unusual, and very full garden.

Artificiosa totius logices descriptio (Artificial Description of Logic in Its Entirety), 1614, designed by Martin Meurisse and executed by Léonard Gaultier. Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, Cabinet des Estampes, Brussels.

These thesis prints were teaching tools that assisted philosophy students in memorizing the body of knowledge necessary for their discourses; by studying the print and winding their way through the garden, students learned corresponding lessons. Enlivened trees of knowledge, thesis prints, and Blome’s diagrams reveal the many ways people have attempted to make information approachable and comprehensible through visual imagery. Blome’s use of the geometric form of the ellipse seeks to establish control over the expansive and chaotic proliferation of knowledge in the early modern world.

Leave a Reply