The (Ethical) Raider of the Leather Pocketbooks

By RJ Lara, WPAMC Class of 2019

You might be surprised by the things one can find stowed away in the folds and pockets of historic leather pocketbooks. Handwritten family trees, paper account books, ghosts of coins, and old stamps are some of the more common finds. Whereas, travel logs, private diaries, fragments of nineteenth century silk textiles, and locks of hair belonging to the pocketbook’s owner are some of the less common ones.

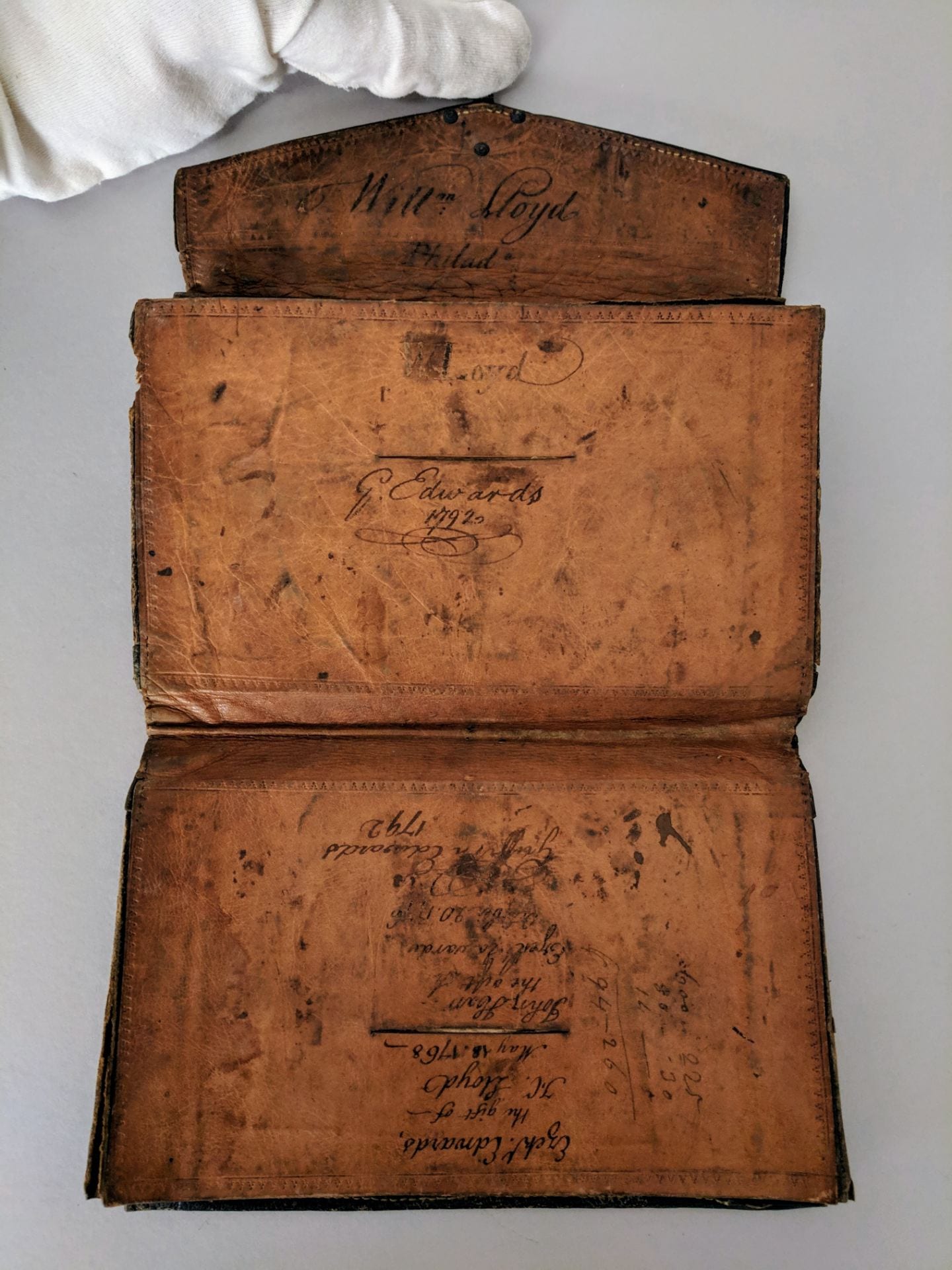

Exterior and interior views of the “William Lloyd” Leather Pocketbook at the Chester County Historical Society. The exterior has an ornate metal lock plate with the initials “WL” engraved on it. On the interior, several names and dates are handwritten in black ink. William Lloyd’s name is written at the top.

Rediscovering such finds during the month I spent researching leather pocketbooks–of my four-month internship surveying leather objects at the Chester County Historical Society–made me truly feel like the leather jacket wearing, bullwhip wielding, fedora garnished Indiana Jones, albeit a much more ethical and ‘care-in-handling’ version. Each of the two hundred pocketbooks I unfolded revealed distinct aspects of Chester County’s rich history. However, not even in my wildest dreams could I have envisioned what I found in one ornate pocketbook, an unidentified 1798 engraved copper-plate by Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin of the profile portrait of Anthony Morris Buckley. No, stowed away I did not find a Saint-Mémin print or one of his physiognotrace drawings, but rather, more extraordinary, the engraved copper-plate.

1798 copper-plate engraved by Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin of the profile portrait of Anthony Morris Buckley. 1994.5093.2, photograph courtesy of the Chester County Historical Society.

Engraved backwards below the profile portrait of Anthony Morris Buckley are the words, “Drawn & engr.ᵈ by Sᵗ. Memin Philad. ͣ .” After fleeing France during the French Revolution, Saint-Mémin lived, worked, and traveled throughout the Eastern United States between 1793 and 1814. Thousands of Americans sat for him within those years, and he became one of the most well-known portraitists of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. From roughly 1798 to 1803, Saint-Mémin set up shop in Philadelphia, and it was in his first year in the City of Brotherly Love that Anthony Morris Buckley sat for the artist.

The artist’s attribution line reads, “Drawn & engr.ᵈ by Sᵗ. Memin Philad. ͣ .” Saint-Mémin engraved the words backwards so that when the ink covered copper-plate was pressed against a piece of paper, the words on the resulting print would read properly from left to right. 1994.5093.2, photograph courtesy of the Chester County Historical Society.

Anthony Morris Buckley’s life (December 7, 1777 – April 6, 1845) was that of a character from Indiana Jones. He was born on his father’s “Hague Plantation” in Demerara, South America, now the country of Guyana. Buckley was a descendent of the prominent Morris Quaker family of Philadelphia, and his father, William Buckley, was a wealthy merchant and sugar plantation owner in the slave trading colonies of the Dutch West Indies. Anthony followed his father into the merchant trade, and upon completing his education in Philadelphia he sailed for Guangzhou (Canton), China in the Spring of 1799, as supercargo, on the ship “Ariel.” According to family history, before Buckley departed, “he had his portrait taken (in 1798), by Saint Memin, as a memento for his friends, an East Indian voyage, being, at that time, considered a hazardous undertaking.” [1] Subsequently, he and the rest of the passengers on the ship were captured by French privateers on the Ariel’s return trip a year later. However, Buckley’s Saint-Mémin portrait–printed from CCHS’s copper-plate–was not his final legacy. “After many vicissitudes,” Anthony Morris Buckley returned safely to Philadelphia in July of 1800. This unfortunate event did not deter Buckley from sailing abroad. The final voyages of his eventful life were to Lisbon, Portugal in 1811 and Cadiz, Spain in 1812.

1798 print of Anthony Morris Buckley by Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin. This print was made from the engraved copper-plate (1994.5093.2) at the Chester County Historical Society. The Library of Congress, National Portrait Gallery, and National Gallery of Art also hold 1798 portrait prints of Anthony Morris Buckley. The writing on the back of the print identifies Buckley as the sitter. The note is signed by the grandson of Buckley’s sister, Howard Edwards. 2011-98-12, Gift of Ann M. and William B. Carey, 2011, photograph courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

So, how did a Saint-Mémin copper-plate find its way into a leather pocketbook? The answer lies in ink on the leather interior. Written on each fold of the pocketbook are the names of the men to whom the object was passed down. William Lloyd of Philadelphia is believed to have been the original owner. From the Lloyd family it was gifted to Ezekiel Edwards in 1768. After passing through the hands of a John Ham, it returned to the Edwards family, in 1792, by way of the final name on the pocketbook, Griffith Edwards. Griffith was the paternal grandfather of Howard Edwards, and it was Howard’s maternal grandmother, Sarah Powel Buckley, who was the sister of Anthony Morris Buckley. Howard Edwards also inherited much of the Morris and Buckley family papers, including an original Saint-Mémin print of Anthony Morris Buckley that is in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Written on this interior fold are the names of the men who once owned the pocketbook. The first lines read, “Ezekiel Edwards, the gift of H. Lloyd, May 18, 1768.” Written next is, “John Ham, the gift of Ezekiel Edwards, October 20, 1776.” The final name and date are, “Griffith Edwards, 1792.”

1994.5093.1, photograph courtesy of the Chester County Historical Society.

I encourage all of my material culture and museums friends out there to take five minutes and just examine that red rotted, CDC alarming, odd looking leather object that is sitting on the back of the last shelf in storage. Five minutes, and two Google searches, is all it took to unfold the fascinating history of the Saint-Mémin copper-plate and the leather pocketbook it was found in. Now, in no way, shape, or form is this pocketbook in rough condition. In fact, it’s leather, metal work, stamping, and hand-marbled paper are quite magnificent, but even leather objects like this often go unstudied in museums. So, give some love to the leather in your collection, and spend some time researching the material at other institutions. CCHS’s two hundred pocketbooks are the most remarkable American leather pocketbook collection I know to exist. Further investigation of the collection by researchers and fellow (ethical) raiders is welcomed!

[1] Moon, Robert Charles. The Morris Family of Philadelphia, descendants of Anthony Morris, born 1654-1721 died. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Robert C. Moon, 1898.

Leave a Reply