Two Artists and an Armadillo in Antwerp

By Erin Anderson, WPAMC Class of 2020

Untitled (America), copy of an engraving by Adrien Collaert II after Maarten de Vos’s design, ink on paper. Photo by author, Image courtesy of Winterthur Museum.

During my very first visit to the Winterthur museum, this engraving with its comically oversized armadillo instantly intrigued me. I just knew that something that weird was bound to have an interesting story behind it.

With a bit of research, I learned that this print is a later copy of a 1589 engraving by Flemish artist Adrien Collaert II (c.1560-1618) based on a design by fellow Flemish artist Maarten de Vos (1532-1603). It is one of four prints in an allegorical series depicting “The Four Continents” – Africa, Asia, America, and Europe – each represented by a woman astride a symbolic steed, surrounded by attributes of her culture. Here, America is shown as an Indian Queen with a feathered headdress, a simple cloth skirt, holding a bow and an axe with a quiver strapped to her back which are all typical for allegorical portrayals of America in the sixteenth century.

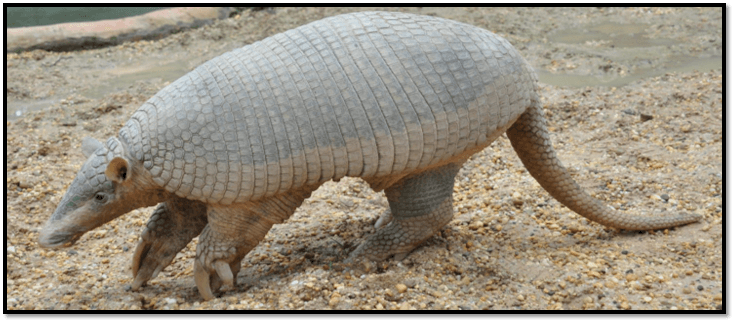

Yet none of this information answered the most burning question I had: what in the world is going on with that armadillo? To learn more, I contacted zoologist Katy Banning who identified the armadillo in the print as the giant armadillo (Priodontes maximus), a species native to South America. Out of more than a dozen possible species of armadillo, she was able to positively identify the animal in the engraving. How? Because Collaert and de Vos had carefully illustrated the unique characteristics of this particular species with an impressive degree of scientific accuracy.

The sixteenth century saw a growing interest in scientific realism, and a large number of artists including Collaert became specialized “animalists” who were often commissioned to produce scientifically accurate illustrations of natural history specimens, especially exotic creatures from the New World, often basing their designs on a combination of written descriptions and physical specimens found in private collections and cabinets of curiosity. The carefully-executed zoological details of Collaert and de Vos’s armadillo suggest that one or both of the artists were using a preserved specimen to inform their illustration and engraving. Armadillos are the most common New World animal in early modern natural history collections both because their bony plates preserve remarkably well and their striking unfamiliarity to European audiences increased the wondrous effects of the cabinets of curiosity.

Collaert and de Vos both lived and worked in Spanish-controlled Antwerp, one of the most active port cities in Europe where enormous quantities of trade goods, world travelers, and exotica passed through every day. Transatlantic trade routes dominated by Spain and Portugal flooded Europe with South American exotica, including animals like the giant armadillo. As a central hub for international exchange and a prominent location for artists working on natural history projects, Antwerp was more likely than most other European cities to have preserved animal specimens available for study by artists like de Vos and Collaert.

In the end, I finally had some answers to my questions about how this print had come to be. It all came down to two artists and an armadillo in Antwerp.

Leave a Reply